In Capital, Karl Marx discusses how the products we buy are separated from any recognition of the people who produced them. If I want to buy a TV, I’m unlikely to be involved in any kind of interaction with the people who made it. I don’t see the factory where they worked, I don’t have any idea what the conditions were like, I have no specific idea where it was made, outside of “Made in _____” written on the box. Instead, I exchange money for the TV at a store that almost certainly had nothing to do with manufacturing the TV; no one at Best Buy or Wal-Mart could tell me any more about the specific conditions of production than what I can figure out from reading the package.

Marx referred to this as commodity fetishism. The social relations embedded in products — the fact that someone made that TV, under particular conditions, making a certain amount of money for their labor while producing profit for their employer — are obscured and workers become invisible. Instead, we focus on how much we pay for it, and which store charges the least. Marx argues that relationships between workers, employers, and consumers are presented to us simply as relationships between things; we exchange paper money (an abstract measure of our labor) for commodities, and we rarely pause to think about how the price of a TV is determined by the worth placed on workers in a particular place at a particular time.

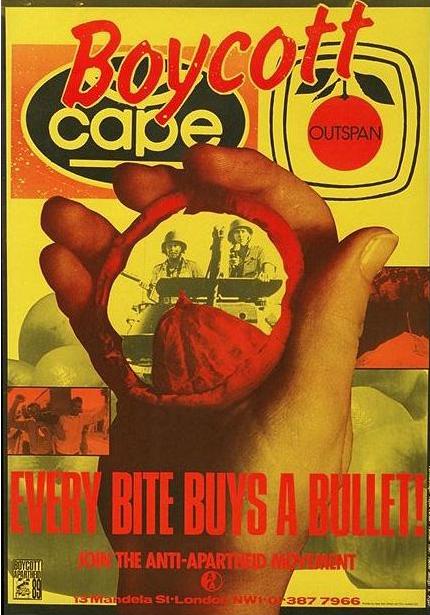

Social activists concerned with working conditions, environmental impacts, and a range of other concerns often push back against commodity fetishism, attempting to make the social relations of production visible to consumers again. Craig Martin of Religion Bulletin provided an example from South Africa’s Apartheid Museum. This poster, produced during the struggle against apartheid, calls for a boycott on South African fruit (UPDATE: A reader found a larger image so you can see more detail; via):

The visual of workers soldiers superimposed on the fruit, with workers and protesters in the background, and the phrase “Every bite buys a bullet!”, remind consumers that items they buy having meaning for the world around them, and that they aren’t just exchanging money at a grocery store in return for that fruit; they are buying into a system of production that provides profits for a racist government, which uses those profits to buy military supplies used to enforce its brutal, unequal racist policies.

As Martin says,

In Capital Marx says that commodity fetishism presents relations between men as relations between things — and this poster is a powerful example of an attempt to demystify commodities and reveal that they are in fact relations between human beings.

Comments 12

gasstationwithoutpumps — November 25, 2011

I was going to complain that the image shown is of soldiers, not workers, but I found a higher-resolution scan of the poster at

http://static.wix.com/media/243046711086f58fbb556cb796373cda.wix_mp

and realized that the unrecognizable image on the left edge of the poster is probably of workers.

From a graphic design standpoint, this poster does not read well from a distance, so the use of a tiny scan is not very good for showing the point the writer wanted to make.

T. Mueller — November 25, 2011

I agree with the points made in this article, but changing things is no small undertaking. We have advanced beyond the point of bartering and trading, and most of the industrialized world would not be able to buy all of the nifty electronics and other goods that we do if it were not for the slave-wage labor in developing countries. Since we would find it difficult if not impossible to live without these goods yet feel guilty about the manner in which they were produced, we would simply prefer to ignore this. Just like how grocery stores and butcher shops don't sell you meat with the head or hooves still attached. If we were reminded that the meat came from an animal that had to both live and die cruelly just for us to have a snack, we would feel guilty so therefore we don't like to think about it.

I'm not saying that this is right but it is true. Changing the social psychology of entire cultures is no small undertaking. It is worth doing, but I am pessimistic about any real changes.

Joe — November 26, 2011

demystifying cashews: http://www.hrw.org/features/rehab-archipelago-abuses-vietnam-drug-detention-centers

Szuko — November 26, 2011

I actually don't think that this is what Marx meant by commodity fetishism. Specifically, I disagree with this: "we focus on how much we pay for it, and which store charges the least."

Marx made a distinction between use value (how useful an object is, what you can do with it) and exchange value (how much it's sold for and how much you're willing to pay); the point of commodity fetishism is that, with the rise of industry, these categories get separated from each other. We no longer buy, say, clothing because it is durable and warm and will last us through the winter - we buy it because it's fashionable. So we DON'T focus exclusively on the price - we as Western consumers also consider lots of other factors removed from the usefulness of the object or its price.

To give a more global example, there's the bizarre dynamics of stock trading, where money and objects gain and lose value seemingly at random - thus, the exchange value fluctuates without the use value changing. This is why objects get fetishized - because they are separated from their use value.

Anonymous — November 27, 2011

This is a feature of capitalism, not a bug. Human intellect is not enough to completely know any but a tiny part of a single stage of production, and even then only in a context that is highly localized in both space and time. Markets allow millions of such contributions to be reduced to a single number: the product's price. With this, people can operate on an economic level orders of magnitude more complicated than what their own or anybody's minds could possibly process. Without this, it becomes impossible for society to rationally compare what people want with the means available to attain it and allocate resources accordingly.

Bill R — November 29, 2013

I doubt today's social activists can motivate any meaningful percentage of consumers to influence the socio-political experiences of large-scale commodity producers. The expense of creating awareness alone is enough of a deterrent. Governments have the resources to do this and politicians across the political spectrum have the ability to develop public pressures to encourage it. And in most cases a clear, black-and-white solution is not immediately apparent; globalization and interdependence produce benefits, problems and complexity.

Complex problems usually require complex solutions. A typical grass-roots solution--the boycott (let's put aside the universally-popular references to Karl Marx)--offers a sledgehammer for work requiring a scalpel. The Times recently commented on the ineffectiveness of this kind of solution in "Boycotting Vodka Won't Help Russian Gays".

http://www.nytimes.com/2013/08/21/opinion/boycotting-vodka-wont-help-russias-gays.html?_r=0

kafkette — November 28, 2015

it's really hard to take seriously a bunch of middle- to upper-middle class academic opportunists talking about marx.