Rising Immigration and Intermarriage

Today we see both increased immigration and rising rates of intermarriage. In 1960, less than 1% of U.S. marriages were interracial, but by 2008, this figure rose to 7.6%, meaning that 1 out of every 13 U.S. marriages was interracial. If we look at only new marriages that took place in 2008, the figure rises to 14.6%, translating to 1 out of every 7 American marriages.

The rising trend in intermarriage has resulted in a growing multiracial population. In 2010, 2.9% of Americans identified as multiracial. Demographers project that the multiracial population will continue to grow so that by 2050, 1 in 5 Americans could claim a multiracial background, and by 2100, the ratio could soar to 1 in three.

At first glance, these trends appear to signal that we’re moving into a “post-racial” era, in which race is declining in significance for all Americans. However, if we take a closer look at these trends, we find that they mask vast inter-group differences.

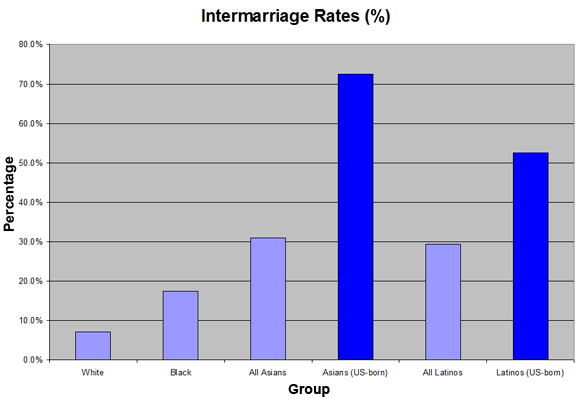

For instance, Asians and Latinos intermarry at much higher rates than blacks. About 30% of Asian and Latino marriages are interracial, but the corresponding figure for blacks is only 17%. However, if we include only U.S.-born Asians and Latinos, we find that intermarriage rates are much higher. Nearly, three-quarters (72%) of married, U.S.-born Asians, and over half (52%) of U.S.-born Latinos are interracially married, and most often, the intermarriage is with a white partner. While the intermarriage rate for blacks has risen steadily in the past five decades, it is still far below that of Asians and Latinos, especially those born in the United States.

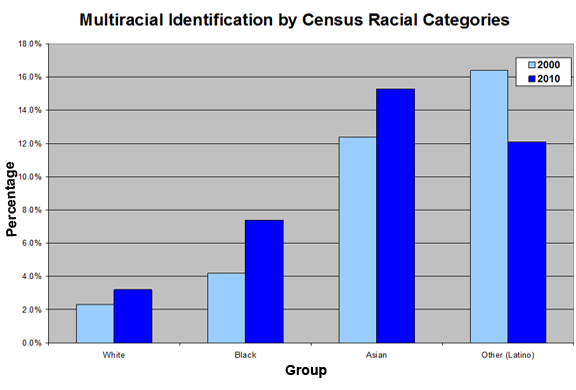

The pattern of multiracial identification is similar to that of intermarriage: Asians and Latinos report much higher rates of multiracial identification than blacks. In 2010, 15% of Asians and 12% of Latinos reported a multiracial identification. The corresponding figure for blacks is only 7 percent. Although the rate of multiracial reporting among blacks has risen since 2000, it increased from a very small base of only 4.2 percent.

The U.S. Census estimates that about 75-90% of black Americans are ancestrally multiracial, so it is perplexing that only 7% choose to identify as such. Clearly, genealogy alone does not dictate racial identification. Given that the “one-drop rule” of hypodescent* is no longer legally codified, why does the rate of multiracial reporting among blacks remain relatively low?

Patterns in Racial/Ethnic Identity

These are some of the vexing questions that we tackle in our book, The Diversity Paradox, drawing on analyses of 2000 Census data, 2007-2008 American Community Survey, as well as 82 in-depth interviews: 46 with multiracial adults and 36 with interracial couples with children.

Turning to the in-depth interviews with the interracial couples, we found that while all acknowledged their children’s multiracial or multiethnic backgrounds, the meaning of multiraciality differs remarkably for the children of Asian-white and Latino-white couples on the one hand, and the children of black-white couples on the other. For the Asian-white and Latino-white couples, they may go to great lengths to maintain distinctive elements of their Asian or Latino ethnic and cultural backgrounds, but they believe that as their children grow up, they will simply identify, and be identified as “American” or as “white,” using these terms interchangeably, and consequently conflating a national origin identity with a racial identity.

The Asian-white and Latino-white respondents also revealed that they can turn their ethnicities on and off whenever they choose, and, importantly, their choices are not contested by others. Our interview data reveal that the Asian and Latino ethnicities for multiracial Americans are what Herbert Gans and Mary Waters would describe as “symbolic”—meaning that they are voluntary, optional, and costless, as European ethnicity is for white Americans.

By contrast, none of the black-white couples identified their children as just white or American, nor did they claim that their children identify as such. While these couples recognize and celebrate the racial mixture of their children’s backgrounds, they unequivocally identify their children as black. When we asked why, they pointed out that nobody would take them seriously if they tried to identify their children as white, reflecting the constraints that black interracial couples feel when identifying their children. Moreover, black interracial couples do not identify their children as simply “American” because as native-born Americans, they feel that American is an implicit part of their identity.

The legacy of the one-drop-rule remains culturally intact, explaining why 75-90% of black Americans are ancestrally multiracial, yet only 7% choose to identify as such. It also explains why we, as Americans, are so attuned to identifying black ancestry in a way that we are not similarly attuned to identifying and constraining Asian and Latino ancestries.

On this note, it is also critical to underscore that a black racial identification also reflects agency and choice on the part of interracial couples and multiracial blacks. Given the legacy behind the one-drop rule and the meaning and consequences behind the historical practice of “passing as white,” choosing to identify one’s children as white may not only signify a rejection of the black community, but also a desire to be accepted by a group that has legally excluded and oppressed them in the past, a point underscored by Randall Kennedy.

Black Exceptionalism

But regardless of choice or constraint, the patterns of intermarriage and multiracial identification point to a pattern of “black exceptionalism.” Why does black exceptionalism persist, even amidst the country’s new racial/ethnic diversity? It persists because the legacy of slavery and the legacy of immigration are two competing yet strangely symbiotic legacies on which the United States was founded. If immigration represents the optimistic side of the country’s past and future, slavery and its aftermath is an indelible stain in our nation’s collective memory. The desire to overlook the legacy and slavery becomes a reason to reinforce the country’s immigrant origins.

That Asians and Latinos are largely immigrants (or the children of immigrants) means that their understanding of race and the color line are born out of an entirely different experience and narrative than that of African Americans. Hence, despite the increased diversity, race is not declining in significance, and we are far from a “post-racial” society. That we continue to find a pattern of black exceptionalism—even amidst the country’s new racial/ethnic diversity—points to the paradox of diversity in the 21st century.

——————-

* The one-drop rule was first implemented during the era of slavery so that any children born to a white male slaver owner and a black female slave would be legally identified as black, and, as a result, have no rights to property and other wealth holdings of their white father.

———————

Jennifer Lee is a sociologist at the University of California, Irvine, specializing in intersection of immigration and race and ethnicity. She wrote, with Frank Bean, a book called The Diversity Paradox, that examines patterns of intermarriage and multiracial identification among Asians, Latinos, and African Americans. Lee wrote the following analysis of her research for Russell Sage. And we’re happy to post it here.

Comments 64

Hollis — July 13, 2011

I've long thought that it is the LEGACY of slavery, both internal (culture, self image), and external (societal expectations), that accounts for American black exceptionalism.

This would go a fair way to explain why Caribbean blacks and more recent African immigrants not only achieve differently, and view themselves differently, but are generally agreed to be so by white American society as a whole.

Growing up with the history of slavery internalized, and the knowledge that the greater society sees you a 'inferior', HAS to leave a wound or deficit in ones sense of self.

I do think Obama's 'mixed race-ness' wasn't the deciding feature that made white American's willing to accept him as a possible president (and made the achievement possible to him, in his own mind), but the fact that as the child of an immigrant, he is and was FREE of slavery in a way that most black Americans still are unable to be.

infinitum17 — July 13, 2011

I'm so glad to see that asian-american kids are by and large overcoming their parents' prejudices about marrying someone of another nationality or race (I know this isn't universal, but trust me, it's widespread). As a product of an interracial marriage married to another such person, I am also super excited to see that interracial marriage is on the rise!

Umlud — July 13, 2011

This post reminded me of one of the OKCupid data trends posts (http://blog.okcupid.com/index.php/page/15/). The data from OKCupid include a lot of people (a little over 1 million for this particular post), and it shows some interesting things, such as response rate to initial contacts based on race (black women are more likely to respond than any other group of women and are the least likely to be responded to; white men are the least likely to respond to initial contact and are the most likely to be responded to; Asian and Hispanic women respond more to white men than to Asian and Hispanic men, respectively; etc.)

From their conclusions about inter-racial dating and views of inter-racial marriage permissibility, very few people felt that interracial marriage was a bad idea (only 6% saying that it wasn't permissible). White females, by contrast, were the only group that was more likely to prefer dating someone of their own skin color/racial background (54% preference), while non-whites had an average 20% preference. (FYI, white males stated a 40% preference.)

There seems to be (at least to me) a good correlation between the points made in the OKCupid blog post and the data above, viz Asian and Hispanic rates of interracial marriage (although the data above are of actual marriages, while the OKCupid queries initial contacts and stated perceptions and preferences).

Christianhlozada — July 13, 2011

This article doesn't quite go far enough into analyzing the racial identity of mixed race people. By saying that race can be seen as "symbolic" actually ignores the same hypodescent faced by African Americans. Race in America is based on physical differences, which is an external signifier, and because of it's external nature, you can't really depend upon an internal definition of who you are. I am Asian and White, and while my parents would define me as American or White, I can not in any way pass as white, so my definition really doesn't help me much when I experience the subtle, unexplainable inequities between me and White friends.

C. D. Leavitt — July 13, 2011

Since "Latino" isn't a race and is tied to place of origin, I don't see why it would be surprising that the offspring of Latino/non-Hispanic White partnerships would tend to identify as American or as white. If a white French person and a white American had children in America, wouldn't they be justified in thinking of themselves as white Americans?

There are certainly a lot of excellent points raised here, but including an ethnicity tied to culture and place of origin rather than race muddies the issue. I think the racial attitudes toward different Asian nationalities within America versus African Americans would be more fruitful.

Cocojams Jambalayah — July 13, 2011

I've a number of comments about this post.Here are two comments, in no order of preference:

1. Regarding the sentence "The Asian-white and Latino-white respondents also revealed that they can turn their ethnicities on and off whenever they choose, and, importantly, their choices are not contested by others."

A number of people of mixed racial ancestry post to and comment on http://www.racialicious.com/ and this definitely doesn't appear to be the experiences of those bloggers.

2. Regarding the statement that the Asian-white and Latino-white respondents "believe that as their children grow up, they will simply identify, and be identified as “American” or as “white,” using these terms interchangeably, and consequently conflating a national origin identity with a racial identity.", if all of this is the case, then it is very problematic on a number of levels, since there are obviously more "Americans" than White Americans.*

* I capitolize "Black" and "White" when they are used as racial referents. However, I retained the non-capitolized forms of those references when quoting the article.

Anonymous — July 13, 2011

was she the one married to Richard Pryor? http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jennifer_Lee_%28Richard_Pryor%29#Marriages

Cocojams Jambalayah — July 13, 2011

The referent "Black" and the referent "African American" are confusing and are often

confused with each other.

Fwiw, I'm an African American who knows a number of Black people who have United States citizenship who were born and raised in various African nations, and Caribbean nations. These people are Black, but they may not be African American. On some levels, referring to yourself as African American is a choice for Black persons living in the USA who don't have at least one African American birth parent.

However, regardless of whether or not a person calls herself or calls himself African

American, they are often viewed as African American because people in the USA use visual clues to racially categorize people and many Black people who aren't African American "look" like African Americans.

The confusion of who is and who isn't African Americans is real to families like the "M" family. Both of the parents were born and raised in Kenya. They are both Luo and therefore the couple aren't inter-ethnic.* The couple moved to the USA and now has USA citizenship. Their two sons were born in Kenya and came to the USA long before both were pre-teens. Their daughter was born in the USA. She is the only one who did not have to get United States citizenship. All of the family considers themselves to be Black (and is considered to be Black by other people). On one level, some may say that the daughter is the only one in the family who is African American since she was born in the USA of at least one Black parent. Yet, the two sons and their sister consider themselves to be African American. I believe the couple thinks of themselves as Kenyan American. But every member of this family may be considered African Americans by African Americans and non-African Americans.

* Regarding "inter-ethnic", I think that many Americans aren't used to considering that just as there are multiple types of European ethnic groups, there are multiple types of African ethnic groups. (I use the term "ethnic group" instead of "tribe" in part because "tribe" has negative connotations, and also because I don't see European ethnic groups being called "tribes") I would consider a Black African couple where the husband is from Mali and the wife is from Ethiopia (to use one example) to be "inter-ethnic" instead of "interracial". Yet there are significant cultural differences and perhaps different physical differences in features and skin color between those two Africans. Imo, their offspring would also be inter-ethnic and not interracial. But an African couple where the husband is Maasai and the wife is East Indian would be considered interracial and their children would also be considered interracial. And if they lived in the USA, those children, and their father [although usually not their mother] would be considered both "Black" and also "African American" by most African Americans and also by most other Americans who have been socialized to use skin color, facial features, and hair texture to racially categorize individuals.

One example of an inter-ethnic African American family I know is an African American woman who married a Jamaican man. To cite another example of inter-ethnic African American couple and their children- in one African American family I know, the husband is from Guinea and the wife is from the USA. Their two daughters were born in the USA and the family lives in the USA. All of the members of this family identify as Black and as African American. And they are identified that way by other African Americans I know -and I can only assume-by other African Americans and by other non-African Americans. My personal opinion is that both "Black" [the more inclusive referent] and "African American" [the more limited referent] are valid.Also for what it's worth, my definition of "African American" is a person who has or had at least one Black birth parent or at least one ancestor who is/was Black and who lives/lived in the USA, or is/was from the USA. This definition holds regardless of any slave ancestry.

There's much more that could be said, but I'll end with the statement that [in my opinion as an African American who is aware of some non-Black ancestry in my family, although it's not first generation], the reason why many African Americans don't identify themselves or their children as "multi-racial" is that "multiracial" is so much a part of being an African American that when you say you are African American, it's understood that you probably have some mixed racial ancestry.

Anonymous — July 13, 2011

THe most problematic thing here is that we are only given a snippet of their total findings. Their could be much more nuance in a book versus a relatively short blog post. Just something for us to keep in mind...still great comments all around.

AlgebraAB — July 13, 2011

I could be misunderstanding the original post, but I think I see a major discrepancy present.

The OP states "The U.S. Census estimates that about 75-90% of black Americans are

ancestrally multiracial, so it is perplexing that only 7% choose to

identify as such." So the post begins by referencing black Americans who are *ancestrally* multiracial but the researchers then went on to interview present-day black-white couples. These aren't the same thing.

It isn't surprising to me at all that the majority of black Americans who are ancestrally multiracial don't identify as such. First of all, you're assuming these individuals know this fact. Not everyone is aware of their ancestry going back 250 years or so. If a black individual has some white ancestors who lived 150 years ago, then he or she is "ancestrally multiracial" but that doesn't mean that they're aware of this fact in the present day.

Then there is the issue of everyday relevancy. As many sociologists have noted, race is a social construct. So, if both of your parents identify as "black" and most of those around you consider you "black" but it turns out you have an Irish ancestor some 6 generations back, does it really make sense to identify as "multiracial"? It's very interesting and it speaks to the fact that many of us are much more "mixed" than we would otherwise assume, but I'd imagine it's not that relevant to your everyday experiences. It's much more relevant to an individual whose immediate parents are of two different races, because it's much more socially apparent and it likely plays a much larger role in how that individual is perceived by others in everyday social interaction.

The researchers also left out a critical variable which might shed more light on this phenomenon: race. Asian immigrants are, on average, higher-earning than black Americans. Asian Americans and whites are much closer socioeconomically than blacks and whites are or than blacks and Asians are. Surely the role that plays is worth investigating, no? Latinos are somewhere in between Asian Americans and blacks socioeconomically so, to continue this line of thinking, it makes sense that they'd be somewhere in between in intermarriage rates as well. Still, I'm somewhat surprised by the figures quoted here. I live in a majority Latino area of Southern California and I don't see that 30% figure borne out by what I see personally. It also a low-income area however so, once again, a socioeconomic breakdown might be very illuminating. Of course, as others have pointed out, the situation is much more complex with Latinos because Latinos can be of any race. Is someone who is the child of a white Mexican (i.e. someone of purely European descent) and a white American really "mixed-race"?

John Hensley — July 13, 2011

Nitpick: The final remark correctly describes the rule of slave status in the antebellum south, but that is not the one-drop rule; it's "partus sequitur ventrem" (following the status of the mother). The one-drop rule derives racial status from both parents, and was widely implemented only after Reconstruction.

Gilbert Pinfold — July 13, 2011

There are at least two different items of interest in this post. The first is the inter-group disrepancy in intermarriage rates. This is not explained in the post. Maybe it requires no explanation. The evo-psych people like Satoshi Kanazawa would not find it surprising.

The second issue is more complicated. In Brazil, 'white' is a common identification for those not abviously of African appearance. In South Africa, the centuries old Cape Coloured population (they have not adopted the identity 'Creole' proposed by well-meaning academics in the Nineties) consider themselves separate in identity from 'mixed race' people from recent inter-marriages. The terms 'Coloured' and 'mixed race' may be confused at your peril. And again, the term 'mixed race' is not seen as interchangable with 'Black'.

Confused — July 13, 2011

Why does it seem like these types of studies privilege mixed people that are (racially) white + something other than white??....where are the studies on the racial dynamics between children born with 2 parents of color (i.e., native american and black; chinese and black)??

Most Stressed Women on Earth; Hispanic Birth Rates; Multiracial Identity; And More « Welcome to the Doctor's Office — July 14, 2011

[...] INTERRACIAL MARRIAGE & THE MEANING OF MULTIRACIALITY by Lisa Wade [...]

Skye Savette — July 19, 2011

I think a major part of the reason that a person identifies as black, is that they *code* as black. I'm pretty sure I have another ethnicity in my makeup, but that doesn't stop me from *looking* like a black person to everyone who sees me.

I'm going to feel hurt and angry at the racism directed toward people *who look like me. *

I'm going to feel both misrepresented and underrepresented in the media when I think about people who look like me.

I'm going to feel the prejudice and discrimination leveled against me and others that look like me.

If a guy in the street calls me the N-word, I'm not going to run after him and say, "Well actually, sir, I'm one quarter Indian on my mothers side!"

Anonymous — July 20, 2011

First of all what the hell is wrong is wrong with identifying oneself as black?

Most black people come by their white ancestry through rape and concubinage, why we include the purveyors of sexual exploitation in our family tree? Do you include rapists on yours?

Another reason that the rate of out marriage is so low among black women (it is proportionally quite high for black men) is the racist and sexist ideology that is a part of mainstream America about black women. At a time when record numbers of black women are in college and starting business, black women are routinely seen as ugly (Satoshi Kanazawa), undateable & unmarriagable (ABC news), hypersexual, bossy, emasculating, angry, masculine, ect. If you are going to do a story on this topic do more research, you have demonstrated you have no idea what you are talking about.

Race, remixed « The Crommunist Manifesto — August 17, 2011

[...] makes this phenomenon more interesting is the fact that “mixed” has quite a variety of meanings: Today we see both increased immigration and rising rates of intermarriage. In 1960, less than 1% [...]