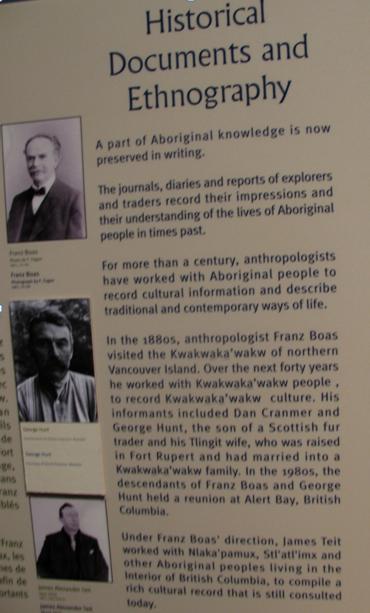

A recent Soc Images post on cultural appropriation highlighted issues of control over the production and representation of images of Indigenous peoples. On a related note, an image I captured during a recent visit to the Canadian Museum of Civilization (or as one of my professors has called it, the “Canadian Museum of Colonization”) highlights similar issues regarding the representation of Indigenous knowledges. This poster was displayed in the “First Peoples’ Hall” of the museum in a section dedicated to “Ways of Knowing”:

Two points are particularly striking. Firstly, the poster portrays the “preservation” of Indigenous knowledges as a project of colonizers and non-Indigenous anthropologists. Rather than attributing control over the production and representation of Indigenous knowledges to Indigenous peoples themselves, the poster depicts colonial “explorers” and anthropologists as the primary agents in these endeavors. Indigenous peoples themselves are merely portrayed as informants, leaving interpretation and presentation to colonizers and anthropologists. In recent years, numerous Indigenous scholars have written about the oppressive nature of this type of approach to Indigenous peoples and knowledges, pointing out how academic disciplines such as anthropology have been essential tools in the study and subjugation of Indigenous peoples as “primitive Others.”

Secondly, the poster presents Indigenous knowledges as static and unchanging, ignoring their dynamic nature and the ongoing experiences of Canada’s Indigenous communities. Canadian Indigenous scholar Andrea Smith* has argued that in settler societies such as Canada, false notions of the disappearance or threat of extinction of Indigenous peoples and their knowledges are at the foundation of cultural imaginations and serve as justifications for the appropriation of Indigenous lands and cultures. In this case, the threat of extinction is implied in the need for Indigenous knowledges to be “preserved in writing.”

This poster provides an entry point for questioning power relations inherent in the production and presentation of knowledge at the Canadian Museum of Civilization and similar institutions. This example demonstrates how the museum portrays a particular view of Canada and its relationship with Indigenous communities, one which ignores the historical and continuing reality of colonialism and its implications.

* Smith, A. (2006). Heteropatriarchy and the three pillars of white supremacy: Rethinking women of color organizing. In A. Smith (Ed.), Color of Violence: The Incite! Anthology (66-73). Cambridge, MA: South End Press.

—————————

Hayley Price has a background in sociology, international development studies, and education. She recently completed her Masters degree in Sociology and Equity Studies in Education at the University of Toronto with a thesis on Indigenous knowledges in development studies.

If you would like to write a post for Sociological Images, please see our Guidelines for Guest Bloggers.

Comments 22

Yrro — May 2, 2011

On the one hand, I can see how the emphasis on the anthropologist's work in cataloging indigenous knowledge, rather on the knowledge itself, can marginalize the contributions of those who actually own that knowledge.

On the other hand, ones sees very similar language used when speaking of recording other oral traditions that are not directly connected to a marginalized group, such as folk music or ghost stories. At some point, for the information to be more widely disseminated it must be recorded. It makes me curious if there was a move toward this by anthropologists or leaders within the indigenous group whose contributions were ignored, or that if an external anthropologist had not decided to go around collecting and reporting on these stories if they would remained as only known within that group.

azizi — May 2, 2011

I cosign what the poster wrote about how the Canadian Museum of Civilization and similar institutions "portray [s] a particular view of Canada and its relationship with Indigenous communities, one which ignores the historical and continuing reality of colonialism and its implications".

However, not to belittle that point, I want to focus on four ther points that I got from this post:

1. Persons from outside a culture shouldn't be the only collectors/recorders of that culture

2. Persons from outside a culture shouldn't be the primary collectors and interpretors of what is collected from that culture.

The assumptions that undergird those two points -and I believe they are correct-are that persons from outside the culture may only collect/record that which they think is important [based on their cultural lens, and their value systems] and they may disregard that which they don't understand/ don't value even though those ideas, attitudes, beliefs, customs might be (might have been) very important to those inside that culture.

3. Persons from outside the culture may misinterpret that which they think they understand but actually don't since they really don't know that culture

4. Since cultures that are alive aren't static, the information recorded by persons inside the culture and/or outside the culture is unlikely to be a true picture of what the culture is like now.

-snip-

To share a "minor" example from my primary interest-contemporary English language playground rhymes & cheers- a couplet from an African American foot stomping cheer/hand clap rhyme which I collected in the early 2000s goes

my name is __ and I'm number 9

kickin it with Ginuwine

-snip-

I'm from that culture though not of the same age as those girls who perform that cheer/rhyme, and I knew that "kickin it" sometimes meant

"socializing with (hangin with)" someone. But because I hadn't kept up with R&B/Hip-Hop culture, I wasn't sure what they meant by the "ginuwine" part of that line. I asked and was told that "Ginuwine" was the [R&B] singer [who was very popular at the time I collected that rhyme version]. However, suppose I didn't ask my "informants" and just collected those words (assuming I valued that recreational material enough to collect it]. I might have wrongly interpreted that line "kickin it with Ginuwine" to mean "really (genuinely) kicking someone or something hard". And that might have resulted in the false conclusion that this was an example of how violent those girls and their culture was, instead of the truth that that line was an example of pre-teen girls' admiration for a teen idol who they wished they could spend some social time with.

See the difference?

Anonymous — May 3, 2011

Are the comments not showing up for this? It says 3 comments but nothing shows.

Anonymous — May 3, 2011

Ah, there it is. Once I posted they appeared. Strange. Sorry about that.

M — May 3, 2011

This is a plaque, not a whole museum. Which absolutely doesn't ignore colonialism, and that Aboriginal culture isn't static.

Secondly, it's not just old white guys collecting information (not anymore). The museum makes an effort to employ Aboriginal-identified people and offers internships as well (http://www.civilization.ca/cmc/media/press-releases/2011/aboriginal-training-program-in-museum-practices), and works with the communities.

Yes, there are still MAJOR questions about appropriation and colonialism at CMC, but taking one plaque and running all the way with it is so lacking nuance it strikes me as awfully dishonest.

Jay Lake — May 3, 2011

Have you ever visited the private museum of Frank Phillips at Woolaroc in Oklahoma? Unless they've significantly reformed it since the last time I was there, the place is a snapshot of anthropology and museum science ca. 1964. It makes the issues cited in this post seem like a very model of contemporary progressive thought.

Bizarre place to see with anything like a modern sensibility.

http://www.woolaroc.org/

Anna Geletka — May 3, 2011

The inclusion of Boaz in the image is particularly striking, considering that Boaz's "informants" went far beyond the traditional meaning of that term, creating fully realized ethnographic accounts and native-language dictionaries. George Hunt in particular worked with Boaz for many years, and was instrumental in shaping Boaz's work and focus.

Anonymous — May 3, 2011

It's particularly striking the the "diary" of an explorer or trader should be considered "Indigenous" knowledge. We are not even speaking here of field work, but simply someone's personal journal. In what way does this constitute Indigenous knowledge? It is the impression of an explorer about his travels presumably - it may give valuable information about how explorers thought, what the cultural views were at the time, the details of daily life as an explorer, etc. but I don't see how a first-person account not even intended to accurately compile Indigenous knowledge should qualify. Of course there were many Aboriginal traders and explorers, but presumably they are not included in this account.

Casey — May 3, 2011

It's somewhat frustrating to see the person credited with shifting anthropology from solely being focused on untrained accounts by traders and people outside of the field and introducing the very concept of objective appreciation of a culture being noted for his use of untrained accounts by traders and denigrated for not having enough of an objective appreciation of culture.

Criticizing history is really easy.

John Jackson — May 3, 2011

Silly Feminists and your penis envy, when will you learn to accept that you cannot have a penis and get back in the kitchen? Quite hating on your mothers and do what you were born to do, cook for us men with penises.

“Museum of the Oppressor”? The Canadian Museum of Civilization and Indigenous Peoples | Eye for Equity — June 20, 2011

[...] recently wrote a guest post at Sociological Images on the Canadian Museum of Civilization’s presentation of Indigenous knowledges, where I used an image from an exhibit on Indigenous knowledges as a starting point for discussing [...]

Anonymous — June 21, 2011

For anyone interested, I finally got around to writing more on this topic, including an overview of some other sources of analysis, on my blog at http://eyeforequity.wordpress.com/2011/06/20/museum-of-the-oppressor/