Cross-posted at Ms. and Family Inequality.

In the early 1990s, Arline Geronimus proposed a simple yet profound explanation for why Black women on average were having children at younger ages than White women, which she called the “weathering hypothesis.”

It goes like this: Racial inequality takes a cumulative toll on Black women, increasing the chance they will have health problems at younger ages. So, early childbearing might pose health risks for White women, but for Black women it makes more sense to start earlier — before their health declines. Although it’s hard to measure the motivations of people having children, her suggestion was that early childbearing reflected a combination of cumulative cultural wisdom and individual adaptation (for example, reacting to the health problems experienced by their 40-something mothers).

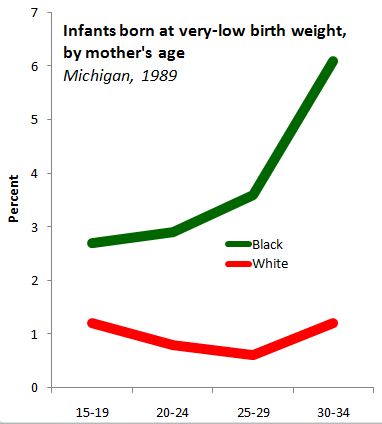

She showed the pattern nicely with data from Michigan in 1989, in which the percentage of first births that were “very low birthweight,” increased with the age of Black women, but decreased for White women, through their twenties:

Source: My graph from Geronimus (1996).

If the hypothesis is correct, she reasoned, the pattern would be stronger among poor women, who experience more health problems, which is also what she found.

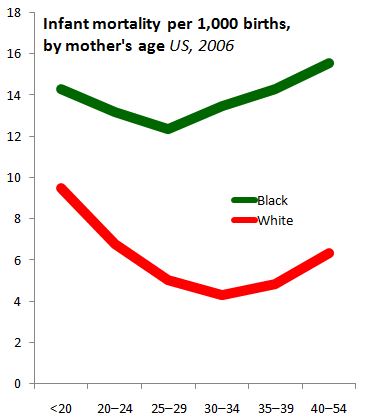

The most recent national data, for 2007, continue to show Black women have their first children, on average, younger than White women: age 22.7 versus 26.0. And the infant mortality rates, by mothers’ age, also show the lowest risk for White women at older ages than for Black women:

Source: My graph from CDC data.

Note that, for White women, mothers have children in the early thirties face less than half the infant-mortality risk of those having children as teenagers. For Black women, waiting till their lowest-risk age — the late 20s — yields only a 14% reduction in infant mortality risk. So it looks like waiting is much more important for White women, at least as far as health conditions are concerned.

The implications are profound. If you base your perceptions on the White pattern, it makes sense to discourage early childbearing for health reasons. But if you look at the Black pattern, it becomes more important to try to improve health problems at early ages — and all the things that contribute to them — rather than (or in addition to) trying to delay first births.

—————————-

Cohen’s previous posts featured on SocImages include ones on the recession and divorce data, the relationship between cell phone use and driving deaths, measuring the number of welfare recipients, delusions of gender dimorphism, and the gender binary in children’s books.

Comments 18

LaNeia — December 29, 2010

I would love to see data adjusting for income - higher income levels for both races and if the data showed disparities there as well.

Julie Withers — December 29, 2010

I'm looking for the source but if I recall, the data shows that disparities exists at higher levels of income. IN other words, a Black male doctor will suffer health issues at levels similar to those of a low income Black man. I just remembered where I saw this! Check out the PBS doc and website for "Unnatural Causes: Is Inequality Making Us Sick?" @ http://www.pbs.org/unnaturalcauses/

Jeremiah — December 29, 2010

Great post with a nice 'wow!' to the data!

heatherleila — December 29, 2010

"But if you look at the Black pattern, it becomes more important to try to improve health problems at early ages — and all the things that contribute to them — rather than (or in addition to) trying to delay first births."

This is exactly what the Office of Minority Health is trying to do with its preconception health campaign, which is actually a campaign against infant mortality in the African American population. Improving health before pregnancy is even more important for avoiding infant death than attending prenatal appointments.

http://minorityhealth.hhs.gov/templates/browse.aspx?lvl=2&lvlID=117

http://heatherleila3.blogspot.com/search/label/preconception%20health

While income and education of the parents is a factor in infant mortality among all races, it does not explain the disparity away. You can even stratify by smoking and it won't make sense. A white woman can smoke while pregnant and still have less risk of her baby dying before age 1 than a black woman who has never smoked. Even the CDC cannot explain this - they even admit it on the website.

misha — December 29, 2010

Thanks for the post. I find really intriguing hypotheses derived from treating agents as smart decision makers learning from their environment. However, I'm pretty skeptical regarding the legs on this specific hypothesis. The curve may be a result of self-selection, rather than rational choice, that is the women giving birth early may be quite different from those birthing later, for both blacks and whites. We may be looking at a bunch of different populations here instead of a fairly homogeneous population making a choice. A young, say, black rational actor who is considering when to have children may find little in common with, say, black women giving birth 30-34, and thus not take these women's infants' problems into account.

I couldn't tell from the abstract that Geronimus took heterogeneity seriously. Even if she tried, the variables she had may not be up to the task. The situation would probably call for some psych or bio measures of heterogeneity. Haven't thought about this much, but here goes a hasty example. Under the weathering hypothesis, one can imagine a tradeoff. For black women, giving birth earlier decreases risk of infant mortality, but also decreases the, say, financial quality of the environment into which the mother brings the infant (i.e. older women have better financial environments). More risk-seeking black women would be expected to have children later.

Alison — December 29, 2010

If you would like to read some of her peer-reviewed articles, I highly recommend the following:

Another piece on the weathering hypothesis: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11759779

This may answer a few questions about income: http://www.rwjf.org/pr/product.jsp?id=15557

Weathering Health Inequality : Ms Magazine Blog — October 11, 2011

[...] post originally appeared at Sociological Images, reprinted with [...]

Health Disparities and Race | Erin V Echols — February 27, 2012

[...] This phenomenon has been attributed to something health and social scientists call “weathering” - which finds that the stress that small instances of discrimination inflict on the body, wear the [...]

Robert Hudson — October 19, 2016

WOW! Great article Philip and fascinating stats.

Pauline Cotton — May 7, 2023

Fantastic paper, Philip, and great statistics. doodle jump