Hegemony is a word used by sociologists use to describe how the status quo can be preserved through consent as well as coercion. One way to gain consent for the status quo, even if it is unjust, is to make the social arrangements that are in the best interests of the dominant group appear to be in everyone’s best interests. When hegemony works, we see social cooperation where there would be conflict

Capitalism is a great example of a hegemonic ideology. Nearly all Americans will argue that capitalism is a fair and effective economic system, even though it, by design, benefits some more than others. Instead of banding together and saying “this may be working for you, but this isn’t working for us,” however, even the poorest of Americans will typically defend capitalism as the best and most just option for the U.S.

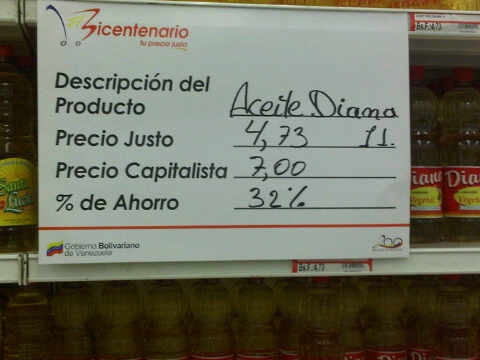

Capitalism, though, is not hegemonic everywhere. F. T. Garcia sent us a link to a photograph snapped by a student of Economics Professor Greg Mankiw and posted on his blog. The photo is of a price sign at Mercado Bicentenario in Caracas, Venezuela. The student translated it as follows:

Description of the product: Diana Oil.

Fair Price: 4,73 Bfs.

Capitalist Price: 7 Bfs.

% of savings: 32%.

In this little narrative, capitalism is an unfair economic system that overcharges consumers. It is by definition not a fair price. A very different narrative about capitalism than we typically hear in the U.S.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

Comments 77

Ranah — November 8, 2010

Prices are balancing multiple interests - including the risk of total failure that the investors are taking. Prices help to avoid deficit by hampering people from getting too much, or prevent wasteful abundance of the product on the market. Multiple factors are involved, not just the egoistic, personal interest of the end customer.

So what is a "fair" price for you? Lower price? Non-existent price?

Please leave economics to the economists.

Grizzly — November 8, 2010

The assumption is that for something to be 'fair' it must work for everybody. By this logic, every game I've ever played and lost was unfair.

Ricky — November 8, 2010

" A very different narrative about capitalism than we typically hear in the U.S."

B.S. We hear that every time the price of gasoline increases.

LadyAnthros — November 8, 2010

Well Lisa, these first two comments seem to be proving your point about hegemonic ideology quite nicely!

Saying we should leave economics to economists is about as absurd as saying we should leave politics to politicians. The notion of "fair pricing" has nothing to do with "ego", and socialist critiques of capitalism are not about "personal interest" - the opposite in fact. The (rather ignorant) use of these terms here indeed reflects the individualist ideology of capitalism hegemonic thought.

And while comparing economic systems and socio-politics structures to a "game" is problematic in and of itself, the idea of a "fair" game is NOT one in which all players 'win' or have the same score at the end, but one in which some players do not compete with unfair advantages and others with disadvantages -- is this not where the notion of an "even playing field" comes from? We can of course debate what constitutes fair and unfair advantages, but Grizzly's analogy is indeed a great example of hegemonic ideology, flatly dismissing alternative perspectives without even cursory consideration.

Thank you for this post.

Sam R — November 8, 2010

How are they determining the fair price?

Circle A — November 8, 2010

Many Americans do NOT think that capitalism is a fair and effective system. Most Americans are brainwashed into believing that it is just and that if they work hard, that they too can be "successful" and wealthy, but there are many of us who see through it all.

Capitalism is corrupt.

Tom S — November 8, 2010

As one of the primary arguments used to justify capitalism seems to be 'it may be bad, but everything else is worse', it strikes me as being somewhat ironic that the same narrative is in place here- the point the sign makes being not 'look how good this price is' but 'look how much worse this price could be'. In both cases, I rather suspect the alternative presented is somewhat illusory.

It's also strange how closely this mirrors the signs grocery stores in the US will put up, showing you how much they're saving you over their competitors. To me, it comes off as though Venezuela is less of a socialist state and more an enormous co-op, working internally on a different economic system but still in a larger sense in capitalistic competition with its rivals.

Sasha — November 8, 2010

This is an interesting post & thread. Unfortunately, one of the main effects of a capitalist economy is often to wildly distort the price to the consumer _downward_. This happens because great incentives are created for firms to externalize as many costs as possible (environmental costs) as well as to depress wages as far downward as possible. This includes using resources to artificially depress prices by doing things like paying off regulators, undermining workers' abilities to organize, etc. So in the case of Diana Oil on sale in this picture, a 'Just Price' would actually include the price if all workers involved in the production chain were paid a living wage, all environmental costs, from resource extraction to production to transportation, etc., were offset. A price like this is not necessarily affordable to consumers, though, unless they themselves are also receiving a 'Just Wage.' Instead, we have a global economy oriented towards very high rates of consumption by an overpaid, tiny minority of the world population.

Sam — November 8, 2010

This is example a great way to get people to think about the hegemonic pull that capitalist ideas have in the U.S -- love it.

But you haven't taken the critique far enough. It needs to be noted that this sign itself is a ALSO a tool of a hegemonic ideology -- namely, the authoritarian (anti-capitalist) ideology of Venezuala's government.

Think about it this way. The Venezuelan state institutes price controls in order to protect its own interests, and uses signs like these to convince the people that the price controls (and authoritarian government in general) are also in their interests. Classic case of ideology.

This is a standard challenge for ideology critique: how can we ensure that the tools of critique are not themselves products of an ideology? Is that ever possible?

Ian — November 8, 2010

I think part of the problem is that "fair" can mean so many different things. Is a "fair" price or deal an equitable one? a just one? an agreeable one? Those would all have very different answers.

I'm not sure I agree that most people would claim that capitalism is a fair system. It doesn't really conform to many of the standards of fairness I can think of. I think most people would agree that it's an effective and efficient system, and I think they'd be right. I'm not saying that capitalism is perfect, but the problems it has tend to be less bad than the problems of distributing wealth in other ways.

George — November 8, 2010

The sign nicely illustrates the point of the post, but it is in itself meaningless. How is fair defined? Who put up this sign? Perhaps it was mandated by the increasingly dictatorial government.

"...even though [capitalism], by design, benefits some more than others."

Capitalism, by definition, has no design. It is the economic system that emerges when there is a free market. Prices are set by the negotiation between producers and consumers as mediated by the market. While in reality there are slight deviations from the free market (some implemented in attempts to make it "more fair") there is certainly no preference for any particular group built into the system "by design".

I am disturbed that Venezuela is being held up in any way as a model. It may be anecdotal, but the Venezuelans I know are very upset by the increasing power of the state over their lives.

Jake — November 8, 2010

I think this graphic is being misunderstood. The student describes the grocery store in which this is sold as a 'chain of private markets'. The stores are privately owned, meaning they are owned by capitalists. Creating an artificially high, and meaningless, price as a point of comparison so as to give the customer the illusion that they're getting a deal is something nearly all retail stores do. 'BUY THIS CASHMERE SWEATER IT'S 75% OFF, DOWN FROM $600!' What a deal! Not...

This seems to me more about the ability of capitalist system to commodify and profit from elements that might pose a threat to it. A Che t-shirt sold by an MNC is another example.

M Jacobs — November 8, 2010

Matt Taibbi has a line in his latest book that goes something like "organized greed will always win out over disorganized democracy." He's right. So we can either go Banana Republic all the way, or we can get serious about regulating the crap out of corporations, the finance industry, the insurance industry, etc.

As to a purely free market, no thanks. Unless you think 19th-century pictures of little kids working in factories are an example of the good old days.

FTGarcia — November 8, 2010

Interesting analysis. Not what I thought of when I submitted it, but I'm not sure if I had much of a point in any case. It struck me as interesting because it is an example of the "fictitious discount" seen outside it's normal private context, and in this way, it also struck me as amusingly absurd because you can easily imagine the exact same numbers being posted when the store was privately owned, except with "Regular" and "Sale" substituted for "Capitalist" and "Fair."

Since the bureaucrats who became responsible for the chain probably don't know nearly as much about distributing food as the previous owners, it's likely that they did, in fact, simply re-label the same marketing device with a different ideology.

larrycwilson — November 8, 2010

If I get what I want, that's fair. If you get what you want and I still get what I want, that's also fair. If you get what you want but I don't get what I want, that's unfair.

nomadologist — November 9, 2010

Adam Smith defined "natural price" as the cost of raw materials and labor. If you were selling something just to recoup your initial investment, you'd sell it for its natural price. You'd have market equilibrium in this scenario; markets without capitalism. But under capitalism, the point is to invest money (capital) in means of production and labor power in order to produce a commodity which you will sell for your original investment plus a little more so you can reinvest the surplus value in more labor power and better means of production to produce commodities...etc.

Jeff Kaufman's second link describes the sign as showing not only "fair price" and "capitalist price" but also the "cost of production," with the fair price being only slightly higher than the cost of production. The fair price isn't Smith's "natural price"; I'm assuming it's calculated by subtracting the surplus value that the capitalist would keep as profit, but that doesn't really answer the question of how they came up with the number they did. The system is still capitalist, but it's the state itself that is the capitalist.

jake — November 10, 2010

There seems to be a lot of confusion here. Capitalism does give you low prices, as low as any consumer could ever ask for, but....

1) you need competition. Only if there is competition do prices stay low. This is a big if. Because, some employees will carve out for themselves a special place in the market (lawyers, doctors, accountants) to the extent they can't prices will fall.

The same applies to big business. Typically food companies, banks, etc.. buy up all the small fry and make the market as close to a monopoly as possible. We see this all the time. A government that is vigilant and breaks up monopolies will make it work. Unfortunately, politicians can be corrupted. Often they will help the monopolies.

Fair price doesn't really make sense, because it sounds arbitrary. Fair to whom? The consumer? The merchant? Fair as in takes into account the profit of the merchant suppliers and employees???

Donald Rilea — November 13, 2010

Interesting debate thus far. Frankly, know practically jack about economics myself, so much of what's been stated here is new to me.

But, it seems to me that one of the big problems with capitalism is that while it's very efficient at creating goods and services, it tends to be much, much poorer at distributing them widely enough throughout a given society.

Also, and this is where many pro-capitalists and pro-socialists(For the record, would be a Social Democrat if a viable social democratic party existed in the US)often go wrong, I think, is in debating the respective merits, or lack thereof, of their systems, without keeping in mind the effects of environment, culture, social norms and mores, and their histories.

Am going to use, and please pardon my using a pop culture reference as an example here, but, for those of you who may remember the old Rodney Dangerfield comedy "Back To School", in which Dangerfield's character, a working-class fella made good as a construction contractor, points out to his economics professor, who's laid out a basic level description of how a company starts up in business and works, the roles played by unions, pay-offs to gangsters and the like, much to the former's displeasure.

Well, it seems to me that their arguments both have some merit, the professor's as an academic, if over-simplified, description of how a business gets started in a modern(at least, in the 1980's)capitalist society, and Dangerfield's character's as an apt, even if crudely put, counter-narrative of the factors that actually go into that process.

It's one thing to state how a given system should work in theory, whether capitalism, the various forms of socialism, mercantilism, feudalism or other such systems. It's quite another to implement and see in fact, because so many factors, like the ones have mentioned above, play into it in ways that even the originators of these systems could neither know about, nor for which they could account.

Marxist-Leninist socialism, as Milovan Djilas pointed out in his 1956 book, "The New Class" succeeded in taking power in countries that were either semi-industrialised or agrarian(I would say, however, that Czechoslovakia was a considerable exception to that assertion), rather than in fully industrialised nations like France, Great Britain and Germany. As a result, one of the main tasks that those nations' new elites felt that they had to accomplish was the industrialisation and electrification of their countries.

Hence, the Stalinist emphasis on heavy industry and the like, at the expense of light industries and consumer goods.

Add on to that, the political and military competition between the West and its allies and the Socialist Bloc and its allies throughout the world after World War Two, with their accompaning pressures, and the necessity, perceived and real, for the socialist bloc's leadership to have large internal surveillance and security forces to control their own people, as well as prevent foreigners from overthrowing their governments, and I think where one can see how those factors ended up heavily effecting how their economic systems worked.

Likewise, in the West, while the roles and pressures on each indivdiual nation in it differed durimg the Cold War period, at least some concessions, just as during the Great Depression, had to be made to both the real and perceived realities of that era's social and political demands.

So, I think that while one can discuss and debate all one likes about the theoretical forms of capitalism, socialism and other economic systems, what most important about them isn't so much the theoretical side of them, but the actual execution.

At least, that's how I see it.