Dmitriy T.M. sent us a link to a story at Slate about (mostly European) “national personifications” — that is, human figures used to represent particular countries, their citizens, or ideas of the national character. Personification is contentious in that it aims to represent a diverse society with a single person, often representing a simple idea. Accordingly, we sometimes see divergent, or even conflicting, personifications.

Many personifications in Europe and areas once colonized by them connect the nation to noble ideas and values through the use of Latin-derived names and the use of robes, poses, and other elements of classic statues and paintings to adorn a female figure. For instance, the United Kingdom’s Britannia (an emblem that first emerged when Britain was still ruled by Rome) is a goddess-like figure wearing a Roman-style helmet who has, over time, come to represent the nation and the idea of liberty:

The U.S. has a similar figure, Columbia:

More popular characterizations also emerge, often representing the national character not through goddess-like imagery but as an Average Citizen. For instance, much more familiar in the U.S. than Columbia is Uncle Sam. He differs from many other national personifications in that he doesn’t represent the U.S. citizenry or the idea of the nation in general; he specifically represents the U.S. government and is best known for wanting “you” to join the military, buy war bonds, and such:

And in addition to Brittania, the U.K. is also personified by John Bull:

According to the Slate article, John Bull presents the British people as middle-class, smart in a common-sense way, and also somewhat suspicious of authority — that is, John Bull is a personification that separates the citizenry from government (the source of authority) to some extent, and thus has been used in many political cartoons to question government policies (whereas Uncle Sam has often been used to advocate them, since he represents the government itself).

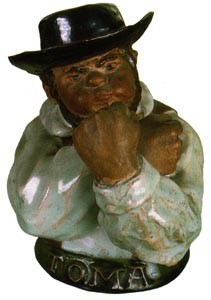

Going a step further, Portugal’s Zé Povinho, a working-class personification, actively mocks the powerful, including political elites:

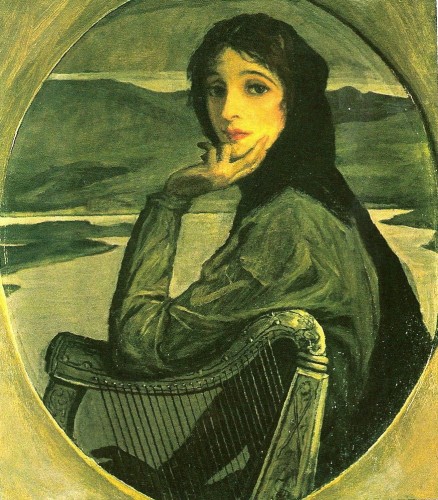

Competing personifications may be used by different political factions. For instance, those in favor of and opposed to Irish independence used female emblems of Ireland. Opponents of Irish nationalism used the figure of Hibernia, represented as the younger sister of Brittania and in need of her sister’s protection from the brutish (male) nationalist forces:

Nationalists responded with Kathleen Ni Houlihan, “generally depicted as an old woman who needs the help of young Irish men willing to fight and die to free Ireland from colonial rule, usually resulting in the young men becoming martyrs for this cause”:

The gender element in these competing personifications is interesting: in both cases Ireland is a woman in need of protection, but who see needs protected by (a stronger sister or men) and from (men in both cases) differs.

So here we have just a small handful of national personifications that may coexist fairly harmoniously while serving different purposes (say, Brittania and John Bull) or actively conflict (representations of Ireland). Various groups in a nation (political elites, different social classes, rebels, etc.) are unlikely to identify equally with a single personification; thus, the figures used to represent a country or its citizens can become sites of political or cultural contention, defining who has the most legitimate claim to being the backbone of the nation (the middle-class John Bull, the working-class Zé Povinho) or framing independence or other political movements.

Comments 34

Birdseed — July 4, 2010

Wikipedia has a page on the subject with a fair few more. Mothers and everymen abound. :)

Willow — July 4, 2010

Not that I'm surprised and all, but it would be nice if the U.S. had someone not white.

Also, something REALLY notable for people who aren't convinced the Tea Party is racist: for all their ranting about the tyranny of the government, you don't see "Uncle Sam is taking my money" on their signs, do you?

Athryn — July 4, 2010

Another good example of this is the logo from the 1901 Pan American Exposition, with two women, one representing North America, and one Representing South, clasping hands. The figure of North America is seen to be lifting South up from something, in keeping with the very paternal views of the turn of the last century.

cøntraba|ançe — July 4, 2010

My comment above notwithstanding, I enjoyed this post very much. Gwen always enriches her posts with a genuine curiosity that I find refreshing.

Luciana — July 4, 2010

just a tiny correction: it's "Zé Povinho", not "Zé pRovinho". Povinho = diminutive for "povo", which stands for "people", "folk", people of a nation.

bxley — July 4, 2010

what about France's Marianne? she specifically represents the French Republic, in contrast with French monarchies or empires. there is a lot of potential in the relatively recent habit of having people vote for a famous Frenchwoman to be "the face of Marianne". so far, it's been femmes fatales like Brigitte Bardot, Catherine Deneuve and Laetitia Casta who have had the honor (which is interesting in itself), but the fact that her features are not fixed or generic opens the possibility that one day the face of Marianne could look Maghrebi or West African.

Elena — July 5, 2010

As far as I have always understood it, part of the reason why national personifications tend to be female is that many Latin names for countries used to have feminine gender: Roma (who was indeed a goddess), Gallia, Germania, Britannia, and so on.

The continents also had feminine grammatical gender (and Europa was also a mythological figure), which didn't hurt, either. Allegories of women personifying the four continents were popular figures since the Renaissance/early modern period.

Howth – Photographed By Infomatique - The Original Infomatique — July 5, 2010

[...] National Personifications » Sociological Images [...]

mercurianferret — July 5, 2010

"For instance, much more familiar in the U.S. than Columbia is Uncle Sam."

I had always thought that the Statue of Liberty was supposed to represent "Columbia."

Too, the symbol of Columbia Pictures, with which I think many people are familiar. (Although I don't know that people necessarily connect Columbia Picture's lady-in-a-toga with a personification of the United States.) Still... more people (I would argue) are familiar with Columbia Picture's icon than with Uncle Sam (as icons).

Emily H. — July 6, 2010

Kate Beaton did a great survey of some political cartoons with Canada, the US, and Britain all personified -- http://beatonna.livejournal.com/57906.html

Pauline — July 6, 2010

Just as an 'outsiders' perspective that you might find interesting, here in Australia I grew up seeing a lot of those Uncle Sam posters (usually parodies of, we had one at the library which was 'You must return your books!' or similar) and always thought he was a famous president of the United States or something. I think because of the hat and maybe facial hair, I'd associate him with Lincoln.

It's interesting to consider how your nation's 'figure' or 'identity', when personified, might be interpreted nationally compared to internationally. Your 'everyman' figure might look opulent and rich to someone from a different country.

This City is a Whore; You Gotta Come » Sociological Images — July 9, 2010

[...] and “cheap” with “satisfaction guaranteed.” We also recently posted about national personifications, fictional or semi-fictional people used to represent countries. This ad campaign, submitted by [...]

Dove Agrawal — November 26, 2012

acha hi h...

Dove Agrawal — November 26, 2012

kal le ana ye pg ko

Propaganda: National Personification | — December 8, 2013

[…] http://thesocietypages.org/socimages/2010/07/04/national-personifications/ […]

Tutelary Goddesses | The Lefthander's Path — November 20, 2014

[…] Slate article “Do other countries have their own Uncle Sams?” […]

The Revolution Betrayed? - American Reformer — March 26, 2025

[…] (the U.S.) are never depicted alongside children in 19th and early-20th-century political art. They don Phrygian caps, laurels, and Corinthian helmets, and they carry tridents, shields, and […]