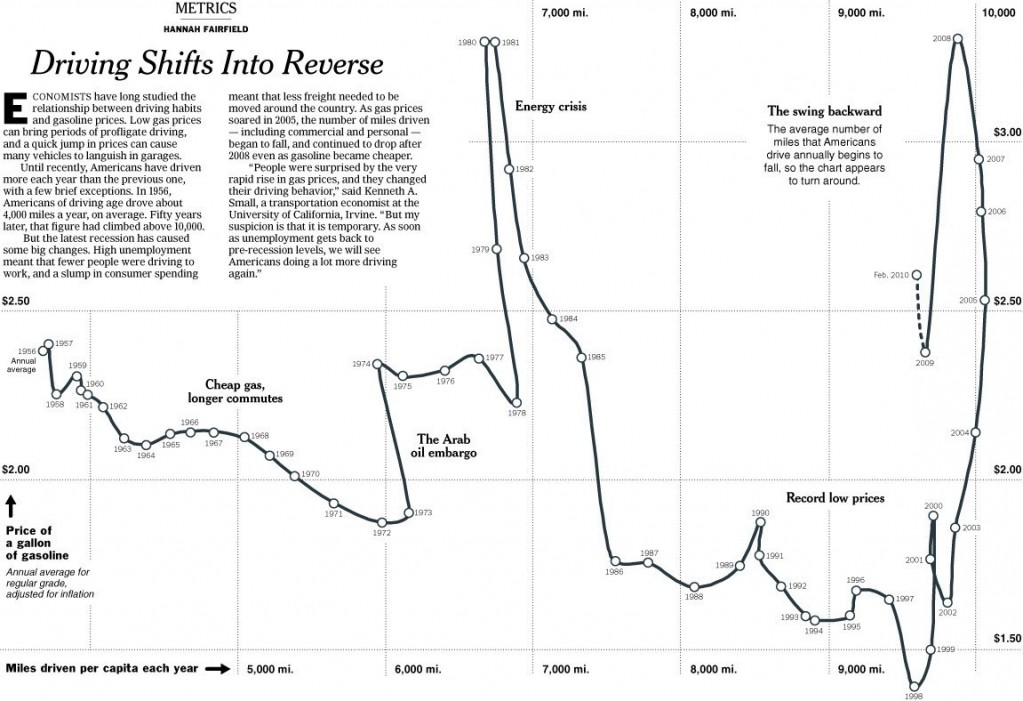

To me this New York Times graphic showing the relationship between gas prices and the average number of miles driven powerfully suggests that gas prices actually have little to do with how much driving Americans do. The vertical axis is gas prices and the horizontal axis is the number of miles driven. The line inside the figure is time.

Basically the illustration shows that the number of miles per year Americans drive has been climbing since 1956. Despite short-term gas price fluctuations, something is driving us to drive more and more every year.

When gas prices do shoot up — such as during the oil embargo, the energy crisis, and the most recent peak — Americans show a modest drop in driving, but it’s not a very large one and we recover rather quickly. During the oil embargo, Americans shaved 210 miles a year off of their driving. During the energy crisis, only 156. The recent reduction in the number of miles driven per year is attributed by the New York Times writer to the fact that so many people are unemployed and, therefore, no longer need to drive to work.

Driving, then, shows only a modest response to high prices. Perhaps the jumps in prices during these peaks — 43 and 106 cents per gallon respectively — weren’t really worth slowing down for? Or perhaps driving is so culturally meaningful that Americans are willing to pay to stay in their cars regardless? Or maybe driving, and driving farther, has become increasingly important over time such that people can’t reasonably reduce the amount of driving they do?

It seems to me that the problem is at least partly infrastructural. I wonder how average miles driven responds, or would respond, to enhancing and investing in public transportation? If we started building denser neighborhoods and got rid of suburbs?

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

Comments 13

Ian — June 16, 2010

That's a cool graph. But I'd like to see one that incorporates the fuel efficiency of the fleet. Assuming rational actors, we'd expect miles driven to correlate with price per *mile*, not price per gallon.

lysh — June 16, 2010

How was this data gathered?

How was the "number of miles per year Americans drive" gathered/measured?

Hmmmmm.....

dr runner — June 16, 2010

I wonder how they measured gas prices! @ lysh....it is obviously a conspiracy.

Chungyen Chang — June 16, 2010

a graph that goes backwards? really now, New York Times?

Frowner — June 16, 2010

I wonder just how much truly frivolous driving most Americans really do and who does it? (National myth-making to the contrary, most USians are working class, don't make huge amounts of money, etc) If I can live in suburb A, where rents or mortgages are cheap, but must work in suburb B because there are no jobs for me in suburb A, I will be trundling across the metro no matter what the economy looks like because I can't afford to lose my job. Because of the decentralization of work and living, it's not even super-easy to carpool unless I'm lucky enough to have co-workers who also live fairly near me in suburb A. If suburb A is really screwed up, I may have to drive my kids to school or drive a fifteen mile round trip for groceries. That doesn't change if the price of gas rises. What's more, if my partner works in suburb L, maybe my partner and I can't even ride to work together; maybe we need two cars!

We often talk as though it's an easy choice to give up your car or dramatically reduce your driving--a simple moral decision, something easily done without or replaced by buses and biking. Let me tell you--I actually gave up my car, after waiting quite a while to get hired at the university in my town. I bike to work, I ride the bus a little--and I borrow my housemate's car once a month for a giant canned goods/toilet paper/laundry detergent run to Target, because even living in a relatively densely settled area, I find it difficult to bring home large and heavy things on the bus. And for me, giving up my car was the result of luck and a lot of planning! Certainly other people could do as I did, if they didn't have a lot of family responsibilities and they were able to live close to work in a fairly dense metro area.

Adrian — June 16, 2010

The article says that people drive fewer miles when unemployment is high, and that they don't generally drive fewer miles when the price of gas is high. This makes a lot of sense to me. For an awful lot of people, commuting to work accounts for most of the miles they drive. Reducing that commute would require them to find another job, another place to live, or both. Relatively few people can afford to live in areas where it is feasible to get to work without a car, and even fewer have the power to change suburban infrastructure. Losing a job means not commuting, and may also reduce driving back and forth to deal with childcare.

When a person who is commuting for work faces an increase in gas prices, he or she might try to earn more money. (But going in to work on weekends, or taking a second job, means more commuting.) Or they might try to reduce other household spending, perhaps buying groceries in bulk (cheaper than the neighborhood store, but requiring more driving to buy them.)

Asa — June 16, 2010

It would only make sense if you compared it to other countries at similar times when they were similarly affected, since the US still has insanely cheap gas compared to many other developed Western nations which drive more distance per capita.

Ed — June 16, 2010

Given the state of politics today, we will be lucky if buses do not disappear altogether in most cities. As for getting rid of suburbs and building denser neighborhoods, those are great dreams that do not have a chance in hell of coming true.

I understand and somewhat agree with Frowner's comment that most people are not able to simply give up their car, any more than we can simply decide to get rid of suburbs. But we make lots of small choices at various points that affect how much gas we use. For example, when buying a vehicle we can look at smaller cars with manual transmissions, rather than large SUV's or pickups. Obvious, a landscape contractor might need a pickup, but an aide at an assisted living facility probably does not. And you can look at the bus routes for your town, and see if you could drive part of the way to work, park, and take the bus the rest of the way. When one does change residences, one can choose to move into a city rather than into a suburb.

In other words, we aren't able to make dramatic changes in our use of oil now, because of the decisions we have made in the past. Which should tell us that as these decision-points come up in the future, we could decide to make the amount of oil we use a factor in what we decide to do.

Miriam — June 16, 2010

So. We have this highway trust fund (in the US) where gas is taxed and put into constructing highways. More highways lead to more suburbs, leads to more driving, leads to more money in the highway trust fund, etc. The very concept of the center of the city being the center of business is dying. The inner city, all over, is falling apart. Meanwhile, by building suburbs further and further from jobs and businesses, it becomes more and more necessary to drive longer and longer distances to work, the grocery store, etc. Wooo urban sprawl!

Now, the highway trust fund is also used to repair roads, and small portion of the money now goes into financing public transportation. So, it is my opinion that somewhat more of the money be allocated to public transit in order to curb the vicious cycle. (and bike lanes, bus lanes, and carpool lanes) I think this graph demonstrates what is so far the consensus of the other commenters: people need to drive, particularly to work, no matter what the price of gas is. Unfortunately, this systemic problem is presented to us as an individual choice/failing. This, I'm pretty sure, is counterproductive to actually substantially reducing the problem.

Rebecca — June 17, 2010

Surely this is related to unemployment.

Looking at the years where miles-driven dropped:

1974: recession

1979: recession

1991: recession (and cheaper gas)

2001: recession (and cheaper gas)

and currently - the worst recession since the Great Depression.

It will be interesting to see if miles driven rises again once more Americans have jobs to drive to.

The Man — June 22, 2010

"got rid of suburbs": hilarious. Better yet: get rid of cars - "problem" solved.

What about the emergence of two-income families? Is it possible that the per capita mileage has gone up because there are two commuters in an average family when in 1962 there wasn't?