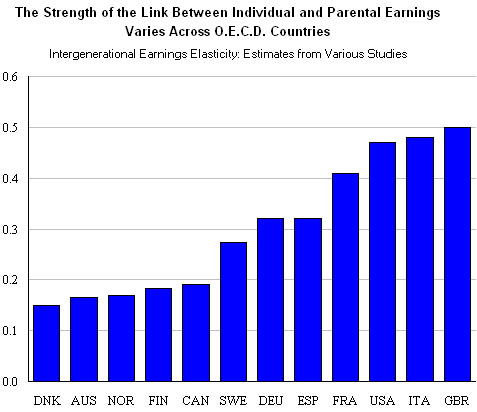

Katrin sent us a great figure comparing the rate of socioeconomic mobility across several OECD nations. Using educational attainment and income as measures, the value (between zero and one) indicates how strongly parental socioeconomic status predicts a child’s socioeconomic status (a 1 is a perfect correlation and a zero would be no correlation).

The figure shows that Great Britain, the U.S., and Italy have a near 50% correlation rate. So, in these countries, parents status predicts about 50% of the variance in children’s outcomes. In contrast, Denmark, Australia, Norway, Finland, and Canada have much lower correlations. People born in the countries on the left of this distribution, then, have higher socioeconomic mobility than people born in the countries on the right. Merit, presumably, plays a greater role in your educational and class attainment in these cases.

The figure shows that Great Britain, the U.S., and Italy have a near 50% correlation rate. So, in these countries, parents status predicts about 50% of the variance in children’s outcomes. In contrast, Denmark, Australia, Norway, Finland, and Canada have much lower correlations. People born in the countries on the left of this distribution, then, have higher socioeconomic mobility than people born in the countries on the right. Merit, presumably, plays a greater role in your educational and class attainment in these cases.

Source: The New York Times.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

Comments 33

Undefined — February 18, 2010

"Merit, presumably, plays a greater role in your educational and class attainment in these cases."

I found this sentence a little curious. What is merit? It seems natural to think, perhaps just on the basis of the explanatory claim, that merit is constituted by a capacity for hard-work, talent, creativity, curiosity, and things of that kind. It's not clear, however, that a child's display of such traits isn't strongly correlated with class. I guess there are (at least) two possible (non-competing) explanations of how class affects opportunity. On the one, money is just of itself something that enhances opportunities, for example because university education is so expensive that family wealth is needed in order to secure it: two equally talented students would enjoy different opportunities simply in virtue of their ability to pay for education. On the other, class background might be important because it fosters those qualities that are otherwise selected for on an 'equal opportunity' basis by universities, employers, etc.

From what I recall of Barry's "Why Social Justice Matters", cumulative inequalities of opportunity are best accounted for by looking at the manner in which class impacts on talent, capacity for effort, freedom from stress, etc. And this suggests (final point!) that there's something a little suspect about using the term 'merit' to denote this complex of properties. 'Merit' suggests not only a basis for desert, but something earned by one's own efforts. The notion that these capacities, linked to morally arbitrary factors such as class (and family background and native endowment), are constitutive of 'merit' is therefore close to absurd, and quite probably an ideological tool of capitalism. But perhaps that's not what 'merit' is supposed to denote?

Jeff Kaufman — February 18, 2010

The USA is large and diverse, which confuses the issue. Imagine calculating this figure for the world as a whole. The correlation rate would be something like 90%, because the "variance in children’s outcomes" would be so much larger. If the USA were to split into ~five countries that were each more homogeneous (the south, the notheast, the midwest, etc) this stat would be lower for each of the new countries than it is for the country as a whole now.

Doro — February 18, 2010

This is really interesting from a German perspective, because the lack of social mobility, especially for someone from a poor family, is treated as a serious problem and the media portrays it as particularly bad in Germany. It seems it's a much bigger problem in other countries, but that's never mentioned at all.

Pac Man — February 18, 2010

The Denmark-Austria-Norway findings could be pretty scary. It could mean that upwards mobility is much easier. But, to go along with this, it means that downward mobility is much easier.

Alternatively, it just means there is overall less variability in the incomes of Denmark-Austria-Norway citizens.... The high variability in the U.S. could be driven to a large extent by extreme data points in the U.S. (a small number of people with extremely high wealth drive most of the correlation).

katy — February 18, 2010

I'm Australian and yes, it is hard here to break out of being in a low socio economic bracket BUT it is possible and I would say that a large part of this is because it is possible to go to university without having to pay up front. Most people can defer the payment of their university fees until they earn over a certain amount per annum (it was $30,000 when I went in 2002).

Jonathan — February 18, 2010

It would be interesting to see the correlation broken down by mother vs father. Since in primates, social status is determined by the mother's social status, I would think that there would be a consistently greater correlation between the mother & offspring vs the father & offspring.

AR — February 18, 2010

On the subject of merit, I read this recent article, The Fable of Market Meritocracy, which makes the uncommonly heard argument that markets do not reward merit, and that this is a good thing.

So certainly, the desirability of meritocracy is itself subject to debate, never-mind which system promotes more of it.

Sr. Edith Bogue — February 19, 2010

There is an IMPORTANT statistical error in this article.

If the numbers reported are correlations (Pearson r), they measure the strength of the relationship, not the amount of shared variability.

The shared variability is measured by r-squared, the coefficient of determination.

So a correlation of .50 indicates that about 25% of the variability in the child generation is shared or predicted by the parent generation.

While the pattern of correlation is certainly of interest, there's twice as much mobility in the USA, Germany, and Great Britain as the article and readers are assuming.

PLW — February 19, 2010

At least according to the label on the graph, this doesn't have anything to do with correlation coefficients (directly). It's simply the elasticity of childrens' earnings with respect to parents' income. So a estimate of 0.5 means that if parents; earnings increase 10% (all else equal), we'd expect their childrens' earning to increase 5%. That doesn't tell us anything about the degree of unexplained variance across these countries (which surely varies dramatically, as well).

Kat — February 19, 2010

Second try: ANY CHANCE at least ONE SINGLE COMMENTER might address the actual "why" and "how could we chance that" (taking it at face value)?!

Brooks — February 20, 2010

"Merit, presumably, plays a greater role in your educational and class attainment in these cases."

So these days we go data, representation, interpretation, wild speculation?

Why presume that differences in the impact of merit are at work here? Why not demographics (how much variation is there among peers of the same generation?), geography (are children more or less likely to move rural to urban or vice versa), education (are children more or less likely to match parents' education levels), legal considerations (what impact to inheritance or other inter-generational taxes play?), or a host of other things?

It's interesting data, and I'd love to explore the root causes more. But the conclusion seems really spurious. I think most people would agree that a lower correlation (or elasticity, which is *very* different) is more socially desirable. But maybe it's worth following the old school of actually analyzing the data and testing hypotheses before moving on to prescription?

All out inequality « Dark Purple Moon — March 1, 2010

[...] browsing through one of my top blogs – Sociological Images I came across this graph comparing socioeconmic mobility across OECD countries. Taken from Sociological Images (in itself taken from the New York Times). Using educational [...]

The gap between the bottom and top grows ever larger - Business, Finance, and Investing - Page 5 - City-Data Forum — July 5, 2010

[...] [...]