Flashback Friday.

In his book, Authentic New Orleans, sociologist Kevin Fox Gotham explains that originally, and as late as the late 1800s, the term meant “indigenous to Louisiana.” It was a geographic label and no more.

But, during the early 1900s, the city of New Orleans racialized the term. White city elites, in search of white travel dollars, needed to convince tourists that New Orleans was a safe and proper destination. In other words, white. Creole, then, was re-cast as a white identity and mixed-race and black people were excluded from inclusion in the category.

Today most people think of creole people as mixed race, but that is actually a rather recent development. The push to re-define the term to be more inclusive of non-whites began in the 1960s, but didn’t really take hold until the 1990s. Today, still racialized, the term now capitalizes on the romantic notions of multiculturalism that pervade New Orleans tourism advertising, like in this poster from 2011:

Like all other racial and ethnic designations, creole is an empty signifier, ready to be filled up with whatever ideas are useful at the time. In fact, the term continues to be contested. For example, this website claims that it carries cultural and not racial meaning:

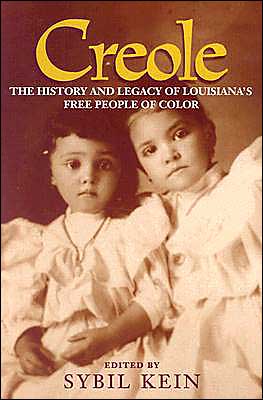

This book seems to define creole as free people of color (and their descendants) in Louisiana:

Whereas this food website identifies creole as a mix of French, Spanish, African, Native American, Chinese, Russian, German, and Italian:

In short, “creole” has gone through three different iterations in its short history in the U.S., illustrating both the social construction of race and the way those constructions respond to political and economic expediency.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

Comments 164

Walter Underwood — November 10, 2009

In Louisiana cooking, "creole" and "cajun" are distinct terms. Creole food has Spanish influences, often using tomatoes. Cajun food has French influences, often using a roux.

It would be interesting to track family recipes to see if that distinguished sub-groups.

K — November 10, 2009

In linguistics, a creole is a type of language that typically develops out of a pidgin. The Wikipedia article is a good introduction.

ptp — November 10, 2009

It seems like the questionable thing here is not the word Creole, because there's clearly a rather broad but distinct regional culture that it describes, but the people who try to precisely define it for ulterior motives. But even that may be innocuous sometimes given that the word just doesn't seem that compatible with our traditional way of associating heritage by region ( American).

A — November 10, 2009

While the US use of the term is interesting, I'm concerned that discussing the Louisiana-based use of this term in isolation from the various Creole cultures throughout the Caribbean and other sites of cultural mixing is missing the point. One can see Louisiana as a culture defined more by its maritime connections than by its US statehood. In most Caribbean nations, the terms "black" and "white" are naive over-simplifications. For instance, a "white" person who is descended from slave-owning families may be considered more a member of the community than a "white" person who emigrated after emancipation, so much so that the right accent can prevent a host of "racial" misunderstandings or violence. Creoles are defined by language, by heredity, by educational and financial affinities. These definitions of Creole have continually been reintroduced to Louisiana's racial and community politics, just as religions in Louisiana bear the mark of continual exposure to multiple African and Caribbean traditions.

heather leila — November 10, 2009

Thanks for posting about this word. It's extremely difficult to wrap your head around the many possible meanings. I remember learning in school that in colonial times, Creoles were the children and descendants of Europeans. By virtue of being born in the Americans and not in Europe, they would always be ranked below those who immigrated and colonized. On the Wikipedia page it says that slaves born in the Americas were distinguished from those born in Africa with the Criulo/Criollo/Creole word as well. So does it mean born in the New World?

I think the linguistic definition can be used as a metaphor for a cultural explanation. A new language possibly with vocabulary from one language and grammar rules based in another. Sounds like the food, the music, the culture of many American nations. It is something new, something created from the old.

What is Creole? « NO NOTES — November 10, 2009

[...] 10, 2009 by nonotes Interesting post on this at Sociological Images (a favorite site of mine): In his book, Authentic New Orleans: Tourism, Culture, and Race in the [...]

Amy — November 10, 2009

Here in Australia, there's been some debate about a store brand of biscuits made by the Coles supermarket chain (the biscuits in question are basically an Oreo clone).

http://www.theage.com.au/national/coles-backs-down-over-racist--biscuit-20091027-hhjx.html

Amy — November 10, 2009

(I neglected to mention that this is relevant because the biscuits are called 'Creole Creams'.)

Andrew — November 11, 2009

Very interesting discussion here. I don't know if I've encountered two people who agreed on exactly what Creole is, but it does appear to be contextual - the word that follows this adjective is crucial.

One slight correction, though: the food website quoted in the last image actually identifies creole as "a mix of French, Spanish, African, Native American, Chinese, Russian, German, and Italian SPICES." From a culinary perspective, this is indisputable, and only tangentially related to the cultural construct of the word. Their comment on Creole culture was quite a bit more sensitive to different identities:

" Those terms are always used in the general area of present or former colonies in other continents, and originally referred to locally-born people with foreign ancestry. Creoles are known as a people mixed French, African, Spanish, Caribbean, Acadians (Nova Scotia, Cajuns), South American, Native American ancestry and on a smaller degree to include Chinese, Russian, German, Italian, Asian Islands, and Australian."

Valentine Pierce — November 12, 2009

Hmmm, interesting discussion. I learned that creole was Spanish, French, Native American and African. Then two versions came around—the lowercase "c" and the uppercase "C". I know that some New Orleans creoles/Creoles migrated as part of a mass Exodus to California in, I think, the 1950s, where they became "white" overnight. Now, thousands live in an around L.A. and claim the "C" version. I find it divisive here in New Orleans, mostly claimed by olive complected people of various descent but only if they grew up in the "right" neighborhood, the 7th Ward/Gentilly. Anyone else find this?

Slimbolala — November 13, 2009

My father's family is New Orleans white creole. In our family's usage (what I'll claim is the more or less "traditional" local usage) it roughly equates to: descended from the original colonial settlers of New Orleans, primarily French but also Spanish (and African) plus additional contributing strands. (As distinct from what my great-grandmother referred to as the "Americans" - others, typically protestant Anglo-Saxons, who moved to the city from elsewhere in the U.S. after the colonial period.) This usage includes both white and black creoles. (The two groups are of course cousins, sharing family trees and last names. During slavery, it was common for white creole men to have a white family with their wives and a "black" family with their slave mistresses. Since it was considered improper to own one's children, the mixed-race children were free and became part of New Orleans' large free people of color middle class, from whom today's black creoles are descended.)

But yes, the contemporary usage has shifted. Ethnically, as you say, it now refers primarily to black creoles. (Black creoles are still a significant ethnic/class group in New Orleans, playing a prominent role in local politics and business. White creoles have, to a large degree, assimilated into mainstream local white culture and don't retain such an obviously distinct identity.) And of course, as you say, in various contexts it just means anything New Orleans-ish or South Louisiana-ish.

Note following up on Walter's comment regarding Creole vs. Cajun cooking: Indeed, the cuisines and the cultures are certainly distinct. And yes, Creole cuisine has Spanish influences that Cajun lacks, though they are both deeply rooted in French cuisine (and both make extensive use or rouxs). More fundamentally, they're two very distinct populations, Creoles residing primarily in the city of New Orleans and again descended from its orignal French, Spanish, African, etc. settlers dating back to the early 18th century. The Cajuns are descended from French speaking Acadian exiles who came down from Canada and present day Maine and settled in rural South Louisiana later in the 18th century. Though there are some shared roots (and in in subsequent centuries, there's been plenty of cross-pollination), their cuisines and cultures reflect their distinct histories and locales.

Myriam — March 14, 2010

I love being CREOLE !

Myriam Espritt-Steptoe — March 14, 2010

I love being Creole !

Augustine/Comeaux — August 26, 2010

I am appalled that so many people in America even the so called experts don't have a Clue as to just what is a "Creole"..The Very name itself is defined as a person that has it's Origins in the New World..The word "Creole" in Spanish and Portugese means to "Create" in other words it referred to those first born in the New World Who were neither Black , White nor Native American but a Mixture of All thus a Creates Race or "Creole".

The European Colonizers adopted this word to also include their first born off springs as well...For More than 300 years this word has been abused by every tom Dick and Harry that thought it convenient to be called so..How Can You People define a Culture that Predates America and existed long before America...Creole is Our language and Language defines Culture ..Haitians Are Creoles and Louisiana Creoles whether they are White or Black are Creoles along with Our Caribbean and Indian Ocean Cousins and those first Born in their Colonies..Here We are talking about the Louisiana Creoles not anybody else ..

The original White Creoles disavowed this name , they adopted ,as it inferred Black Ancestry..Let's get it straight and stop this nonsense about using this word so loosely..We do exist and not everyone that say's He's Creole is Creole..You all need to read up a bit more on the subject and stop reading what non Creole People suppose ..It's like a Black Person trying to define what an Asian is

Memorie — August 28, 2011

My mommy is creole,and black native american and indian....

Dduronslet10 — October 22, 2011

I'm so tired of blacks that are mixed calling themselves Creole. Your not your Black!!!!!

Lakesidetrombone — November 25, 2011

Growing up in New Orleans it seemed that family members, and others, in order to attend separated movies and other events, wanted to be isolated from dark complexioned family and associates by adopting the difference in referring to themselves as creoles.

Many creoles of color are from Red River area of Louisiana, descendants of Louis Metoyer, born of a wealthy white father with great influence and an African mother.

Enclaves of race sensitive creoles of color are found in Frilot Cove, Louisiana near Opelousas, and Lucy, Louisiana across the Mississippi River from New Orleans. These race sensitive enclaves had exclusive restrictions relegated to persons able to “pasa blanc,” pass for whites.

Now some creoles are striving for special designations as “Creoles” in the United States Census. Most efforts have been denied.

John Soileau — April 15, 2012

Ok, everyone

wants to talk about Creole huh? I agree with most of what has been said in the

post here. I agree that A Creole (now) is of mixed heritage or culture. But I

want to bring to light a piece of information that has not been mentioned in

this website or ANY website that I have found so far speaking about Creoles.

First, let

me tell you a little about me so that you know that I’m not just any Joe giving

an opinion. I am from Louisiana. I speak French. I'm from a heavily French

culture area. Where French speaking is still common today as opposed to New

Orleans. It's a small town called "Ville Platte". Yes, even the name

of the town is French. In fact, I am the first one in my family to speak English

as a first language. My family is ALL of French lineage from Louisiana and has

been here for over 300 years. Magazine and other reporters from France and the

US have come and interviewed my Grandfather. My Family on both my mothers and fathers

sides, all the way up are French. I can trace my family all the way back to

some of the earliest settlers in Louisiana. My last name is Soileau which is

among some of the oldest Surnames, even in France. My mother’s side is the

Billeaudeau's and my fathers of course is the Soileau's. Both names ending in

"eau" that denotes the 1000 year plus Surname. I have studied a bit

of French history and a great deal of Louisiana history/culture.

OK, all

that being said. Now, about Creoles. What hasn't been mentioned is that there

were French people in Louisiana as early as 1609. "That’s before the Plymouth

Rock Pilgrims in the 1630’s" Since Louisiana and New Orleans with it “Vieux

Carre’” (French Quarter or square) was originally colonized by the French and

the first families were all French. Hence the name of the oldest part of the

city, the “Vieux Carre’”, by default the "original" Creoles would

have been French and French only people directly descended from France but born

in Louisiana. Even if the term may have not have yet been applied by proof in

any written account; I know passed down by generations through the families it

was verbally applied. We all know the term is now applied differently and has

even evolved its meaning over the years, but I’m speaking from the roots. Secondly

would have come the Spanish and Italians, then the African & Haitian slaves

in about 1730. So, from this, one can conclude that original Creoles were

French but few decades (almost a century) down the road their was some cultural

mixing and so the name “Creole” would subsequently be applied to a mixed

culture.

P.S.

Related to all this but is another discussion is Creole food, Cajun food, and Cajun

Culture. I have in depth knowledge of this as well for anyone that is interested.

Ok, everyone

wants to talk about Creole huh? I agree with most of what has been said in the

post here. I agree that A Creole (now) is of mixed heritage or culture. But I

want to bring to light a piece of information that has not been mentioned in

this website or ANY website that I have found so far speaking about Creoles.

First, let

me tell you a little about me so that you know that I’m not just any Joe giving

an opinion. I am from Louisiana. I speak French. I'm from a heavily French

culture area. Where French speaking is still common today as opposed to New

Orleans. It's a small town called "Ville Platte". Yes, even the name

of the town is French. In fact, I am the first one in my family to speak English

as a first language. My family is ALL of French lineage from Louisiana and has

been here for over 300 years. Magazine and other reporters from France and the

US have come and interviewed my Grandfather. My Family on both my mothers and fathers

sides, all the way up are French. I can trace my family all the way back to

some of the earliest settlers in Louisiana. My last name is Soileau which is

among some of the oldest Surnames, even in France. My mother’s side is the

Billeaudeau's and my fathers of course is the Soileau's. Both names ending in

"eau" that denotes the 1000 year plus Surname. I have studied a bit

of French history and a great deal of Louisiana history/culture.

OK, all

that being said. Now, about Creoles. What hasn't been mentioned is that there

were French people in Louisiana as early as 1609. "That’s before the Plymouth

Rock Pilgrims in the 1630’s" Since Louisiana and New Orleans with it “Vieux

Carre’” (French Quarter or square) was originally colonized by the French and

the first families were all French. Hence the name of the oldest part of the

city, the “Vieux Carre’”, by default the "original" Creoles would

have been French and French only people directly descended from France but born

in Louisiana. Even if the term may have not have yet been applied by proof in

any written account; I know passed down by generations through the families it

was verbally applied. We all know the term is now applied differently and has

even evolved its meaning over the years, but I’m speaking from the roots. Secondly

would have come the Spanish and Italians, then the African & Haitian slaves

in about 1730. So, from this, one can conclude that original Creoles were

French but few decades (almost a century) down the road their was some cultural

mixing and so the name “Creole” would subsequently be applied to a mixed

culture.

P.S.

Related to all this but is another discussion is Creole food, Cajun food, and Cajun

Culture. I have in depth knowledge of this as well for anyone that is interested.

John Soileau — April 15, 2012

Ok, everyone

wants to talk about Creole huh? I agree with most of what has been said in the

post here. I agree that A Creole (now) is of mixed heritage or culture. But I

want to bring to light a piece of information that has not been mentioned in

this website or ANY website that I have found so far speaking about Creoles.

First, let

me tell you a little about me so that you know that I’m not just any Joe giving

an opinion. I am from Louisiana. I speak French. I'm from a heavily French

culture area. Where French speaking is still common today as opposed to New

Orleans. It's a small town called "Ville Platte". Yes, even the name

of the town is French. In fact, I am the first one in my family to speak English

as a first language. My family is ALL of French lineage from Louisiana and has

been here for over 300 years. Magazine and other reporters from France and the

US have come and interviewed my Grandfather. My Family on both my mothers and fathers

sides, all the way up are French. I can trace my family all the way back to

some of the earliest settlers in Louisiana. My last name is Soileau which is

among some of the oldest Surnames, even in France. My mother’s side is the

Billeaudeau's and my fathers of course is the Soileau's. Both names ending in

"eau" that denotes the 1000 year plus Surname. I have studied a bit

of French history and a great deal of Louisiana history/culture.

OK, all

that being said. Now, about Creoles. What hasn't been mentioned is that there

were French people in Louisiana as early as 1609. "That’s before the Plymouth

Rock Pilgrims in the 1630’s" Since Louisiana and New Orleans with it “Vieux

Carre’” (French Quarter or square) was originally colonized by the French and

the first families were all French. Hence the name of the oldest part of the

city, the “Vieux Carre’”, by default the "original" Creoles would

have been French and French only people directly descended from France but born

in Louisiana. Even if the term may have not have yet been applied by proof in

any written account; I know passed down by generations through the families it

was verbally applied. We all know the term is now applied differently and has

even evolved its meaning over the years, but I’m speaking from the roots. Secondly

would have come the Spanish and Italians, then the African & Haitian slaves

in about 1730. So, from this, one can conclude that original Creoles were

French but few decades (almost a century) down the road their was some cultural

mixing and so the name “Creole” would subsequently be applied to a mixed

culture.

P.S.

Related to all this but is another discussion is Creole food, Cajun food, and Cajun

Culture. I have in depth knowledge of this as well for anyone that is interested.

Johnny — April 15, 2012

Sorry everyone about that first post being doubled up. It was to late to delete so I just reposted the correction. Have a great day. Pazzez une excellente journe'

Falnfastfalnhard — January 4, 2013

This is good to know. My mother for the longest time told me that i was creole. That that was why i was so fair. There would be no problem if i were mixed with these other ethnicities. but to know that i've been claiming something that im not, honestly, makes me feel like an idiot. I've never felt so Ignorant in my hole life. Im white. lol wow damn im stupid. I understand that i am french but definitly not creole.

John Soileau — June 23, 2015

Anyone else have any question? "before asking, read all my post below"

eacomm — October 29, 2015

That Definition is not accurate.

Fumaçastl — April 2, 2016

This is so sad!!!! I saw a cooking show on PBS about Creole cooking, to get more insight into the meal I had learned to prepare, I asked Siri to define creole..... this is the tribal argument I found!!!! How long will genetic crap shots be worn as a badge of honor or viewed as a mark of shame! DAGGGGG!!! I don't even want the recipe anymore!!!!

Karl Lynch — April 24, 2016

My family namely on my father's side is african American and Creole and German, my mom's side is African American and American Indian. So, is it safe to call myself multi racial? I just found out about the Creole mix.

Reina Carrillo — July 3, 2016

I love being Mexican but my mother's family were unique in my upbringing. Hearing Zydeco music, food amazing, french when they don't want us kids listening to their conversation, the family parties etc....its beautiful.

me too — October 24, 2016

Iam a tour guide in New Orleans.Creole means native born and pure white.Blacks were ostracized.Thank you.

G Robinson — December 4, 2016

This is made to be more complicated than it should! Creole can logically be viewed as a people of mixed race ancestry belonging to a particular culture. For example, a Louisiana Creole genetically linked by (Native American, African( certain regions out of Africa tied to Louisiana), France, Spain, Portuguese, German etc.) These core groups blended to establish the culture and people as we know it today! Those who live the culture generally live it because of the family members belonging to the community of the Louisiana Creole Culture. As a former classroom teacher, I stress the importance of teaching about the "Louisiana Territory" as it clearly marked the beginnings of "mixed race" people in the America's!!! What many fail to recognize is that a culture needs certain elements to make it a culture and a people for that matter (particular blend of people (as the aforementioned core groups), cuisine, language, religion, music, arts in addition other traditional characteristics followed by a group over extended period of time) Quite frankly, the Louisiana Creole demonstrates this for over 500 years and still going strong! The concept is the same if you say Puerto Rican…(mixed race people of a particular blend with an established culture) Not everyone in Louisiana is Creole or Cajun for that matter but they very well may follow the culture! There are also those whose relatives are born in LA populate children in other areas but their genealogy still ties them to the LA territory making them LA Creole!

Carolyn Stapleton — March 3, 2017

Such a wonderful conversation. I'm born and raised in Baton Rouge, was married to a Langlois (cajun). Here cajun and creole can be easily recognized by last names, creoles with black heritage are gorgeous. They have softly tanned skin, caramel colored, the most strikingly beautiiful women you will ever see. I also thought creole was mixed by haitian, spanish, french and white. I''ve recently been set straight by a dear friend who has written a book on his creole ancestory, no black, german, spanish..in fact because he's creole his race is listed as black which makes him angry.

All of you have documented well creole, creole white and creole black. There is no confusion about Cajun, Thibadeaux, Gautreaux, Langlois, Hebert (a-bear)...so funny down here, asked to spell Jones there might be a problem, but Boudreaux--you got it!!

Love y'all, from down south, here in good ole Baton Rouge, Bless y'alls' hearts, sha' (short a vowel sound-cajun).

Dupré — April 14, 2017

Everyone, Creoles can be either whites or mulattoes in Louisiana. All this nonsense that Creole is a mulatto person only, is nonsense. I'm a white Creole from New Orleans (white Creoles are also known as "French Creoles" or "Spanish Creoles") and I'm proud of my heritage in Louisiana. We have been in Louisiana for over 300 years. A Creole person is anyone that is BORN in LOUISIANA of FRENCH or SPANISH COLONIAL DESCENT. The New Orleans metro area (the parishes of Orleans, Jefferson, St. Bernard, St, Tammany, Plaquemines, St. Charles, St. John) is full of white Creoles and also there are many white Creoles in Avoyelles and Evangeline Parishes. And we are aware and identify as white Creoles. This includes both French Creoles and Spanish Creoles (both are white Creoles) mulatto Creole people are called Creoles of color or colored Creoles.

And to that person that said white Creoles disavowed the name as if we don't exist anymore, you need to stop reading nonsense books and live in New Orleans like I do and see many white Creoles still here claiming Creole identity. Creole just doesnt belong to Louisiana mulattoes. We white Creoles were the first Creoles in Louisiana. We didn't adopt anything. We were Creoles in Louisiana since the first generations born in Louisiana during colonial times.

Now with that said, I don't want to make a big deal about race because we all are children of God and I accept all races of people.

john guillory — June 17, 2017

Bonjour coma a va. I am from Lawtell Swords area of Louisiana and I agree with a lot said. What a lot of people don't know is the roll creoles played in the freedom fight for all Americans. There was a battle between mix race creoles mostly of French and black ancestors That fought at the battle of the mallet scouts. This story needs to be told it was told to me by my grandfather and it was passed on to him. In short raciest confederate whites heard about a large community of free creoles and they were sent to destroy they're Way of life. The creoles won this battle sending a message we will fight and do anything to ensure freedom . I have a lot of info. On this story as my relatives fought in this battle. Maybe some of you have similar stories.

Bella Noir — February 17, 2018

Bonjour! I am a creole woman, born and raised in New Orleans, La. genetically, I am Native American, African, French, Spanish, and Anglo-Saxon. Being born in New Orleans, we were more colonized and so speak English. Louisiana was sold in 1803 to the English colonizers. The term creole originally meant people born in Louisiana of Native, African, French and Spanish descent, however, when the English took over Louisiana, the term creole was applied to people of French descent to distinguish themselves from the English. They didn’t like each other.... and still don’t. Black people were not ostracized by the creole community as we were not termed blacks , but free people of color. Black people were ostracized by white colonials who wanted to keep English blood pure, therefore anyone who had a drop of African blood was known as black. Hence the one drop rule. It was to keep the races from Mixing. Creoles were already mixed though and the English were narrow in their thinking so EVERY DARK SKINNED PERSON was termed black or African American, even though all of us were not from Africa. This was because the English settlers came with west African slaves. They thought that since we all looked alike, we must’ve been the same. My great grandmothers land was stolen because of this.

So... not every black person in America is creole. Not every black person in America is the descendent of African slaves. Just like not every white person in America is White. French people didn’t call themselves white. They call themselves French.

GiftofDiscernment — April 7, 2018

Creole comes from Criollo.

it is heavily referenced throughout the colonization of the Caribbean- in our case a loan word from the French language. I really enjoyed your post, UNTIL I got to the "empty signifier" part.

With all due respect, WHAT the heck does that mean???

Alonzo Rouege' — April 21, 2018

Bonjour! Comment talked vouz. Very interesting comments, opinions, and in some cases, just plain gibberish. I AM Creole and damn proud of it. My CREOLE spirit exudes with the Creole culture , and culinary Delights. Anyway, to one and all " Laissiez le bon tempts rollier"...

Alonzo Rouege' — April 21, 2018

Bonjour! Some good post. Some not. I am of French CREOLE descent and proud of it. Embrace who u are and remember no one can take who you are away from you. Being CREOLE is not a person who is exclusively white. Gibberish!!!. To one and all: "Lessaiz Le bon tempts roullier "

Lizzie — July 10, 2018

Interesting! I'm a 42 year old American Black woman from Georgia, born of older parents (1930s) and they and their parents(born in the late 1800s and early 1900s) used the term creole to describe American Black albinos. It wasn't until high school that I learned the correct term for those who lacked melanin, was in fact "albino". After learning a little bit about the term "creole" I assumed it must have had something to do with mixed race.....specifically, quadroons and octoroons who had to be more white in appearance than biracials. Hence, using the term to describe albinos.

Stephanie Keesee — October 5, 2018

Your page is racist and not true. I am a descendent from a creole plantation owner who passed for white during the time when that was popular. Know your history and don't just accept the white privileged version of history. Creole was specific to the French (who at the time were particularly obsessed with mixed race people) prior to the purchase of the Louisiana territory from the French. Yes it means a person indigindous to that area however it is referring to the present society which had become a culture of it's own where mixed races we're part of families with money and had some semblance of establishment and success. The dark side of that is it was from mixed races posing as white in order to gain power so the average history book does not talk about it due to the dependents not knowing they were mixed at the time. Due to genetics and better ancestral documents we now know that creole INCLUDED mixed races. My great great great great grandfather being one is them. He was actually a creole man whose lineage predated the purchase.

Ms. Morris — October 26, 2018

Me and my daughter was talking today about the different in colors in our family on both my side and her father. We do know that on myside that my great grand mother was creole and from New Orleans. As well, that her father have relatives that also live in New Orleans right today and he states that most of them are creole. His father was of a very white complex person, just as my great grand mother. Both live here in Arkansas and we consider being African Americans in this country. What I like to know do we have the rights to claim our Creole heritage, also ?

BestChanel — August 13, 2019

I see you don't monetize thesocietypages.org, don't

waste your traffic, you can earn additional bucks every month with new

monetization method. This is the best adsense alternative for any type of website (they approve all websites), for

more info simply search in gooogle: murgrabia's tools

Tori Soileau — August 17, 2019

I agree with John soileau I was born a soileau ( family from grand Prairie, )and ironically I married a soileau from (ville Platt) we have the longest know to the world ties to not only our lives in the u.s but also in France google it I traced my family back to when they came to the states in 1715 all the way back to noèl soileau himself

Eloise — August 17, 2019

Curious how many people want to precisely define creole (to match their own beliefs). When applied to language, create is a pidgin reduced, simplified language and there are creole languages around the world and throughout history from relatively modern Yilan creole Japanese to Middle English. I think there would be more success in separating the linguistic reference from the historic and cultural reference to people.

Theresa Styles — August 30, 2019

My Creole culture comes from my maternal line from East Baton Rouge. My ancestors were of African, Native American, Irish, French, and British.

Theresa Styles — August 30, 2019

My Creole culture comes from my maternal line from East Baton Rouge. My ancestors were of African, Native American, Irish, French, and British.

https://creolecountryliving.com/

New England Bloody Mary with Shrimp Cocktail | Creative Culinary — September 24, 2019

[…] over the years and creates a quite lively conversation as to the origin. Maybe not how we think of Creole today but it seems that the first meaning signified that “original” Creoles would have […]

Rene Cantrelle — November 29, 2019

I’m a white Creole from the greater New Orleans area and a member of the Cantrelle family, one of the oldest and most prestigious French Creole families in Louisiana (ironically the Cantrelle family crest is on the Louisiana state flag) and our family is spread all over south Louisiana from Acadiana to Greater New Orleans and has been present in Louisiana since 1720 originating in France, which makes us here 300 years in just a couple months from now (some Cantrelle’s in Louisiana lost the e on the end of their name over time and became Cantrell).

I was raised by my family that Creoles in Louisiana are the folks born in Louisiana and raised in its local latinate culture and are of colonial Louisiana heritage, but of old world stock, regardless of race. This would include whites, mixed race people and blacks of colonial Louisiana heritage made up of old world stock (Europe or Africa usually). This would also include the Acadian descendants (Cajuns) whom were indeed called Creoles before the invent of the Cajun identity of the 20th century and their separation from their old creole identity. However, this would also exclude Native Americans, but not Native American admixture in a creole person of European or African ancestry.

I would like to add that folks of non-colonial heritage that were born in Louisiana and raised in Louisiana’s local Latinate culture have been creolized and thus by the original old definition of creole, would be considered Creoles too. I don’t see how the muffuletta in New Orleans could be considered part of New Orleans creole cuisine yet its Louisiana born Italian descended creators of non-colonial Louisiana heritage raised in Louisiana’s local Latinate culture were not. Just my 2 cents :)

Magaly Duchene — July 1, 2020

am from haiti I do have french desentthe taino i indian and the spanish wherein Haiti I know the white creole was creolian, do you think amcreole

Angeles — September 20, 2020

Hi, I'm New to this blog! I don't know my father. My father is or was Creole do not know what he could be possibly mixed with. But I'm very fair-skinned my question is when filling out an employment form that asks your ethnicity does anybody else put OTHER because we are not recognized?

A — August 11, 2021

Creole can refer to anyone whose lineage descends from the variety of foreign peoples and cultures that originally settled the lands roughly along the Mississippi prior to the Louisiana purchase, but also includes parts of Canada and the Caribbean. In short, that was when those lands were French or Spanish territory. Missouri French and others whose decent can be traced before the influx of Easterners anglicized our street and place names, degrading those speakers of non-English languages, and assimilating us into their historical narratives, are still Creole. It’s not just a term for New Orleans or people whose geographic location in the remote bayou allowed for the French language to endure. Look deeper than language to common cultural practices (e.g., cooking, gardening, folk remedies) for cohesion among various Creole groups.

Nicolas Picou — October 30, 2021

Hello to all. My name is Nick Picou and I am from the Picou and Fortier families in New Orleans in south Louisiana and I’m a Creole. Me and my family, we are New Orleans Creoles of French and Spanish descent (we are the white type Creole, in other words creole white people) and my family lived in the French Quarter (Vieux Carré) on Royal St. in the early years in New Orleans and had been in the French Quarter since the 1700’s, but sometime around the year 1900 the family left the French Quarters (but still owned the property) and the family moved on Esplanade Avenue around Bayou St. John and the City Park/Fairgrounds area. The family today is spread between the Bayou St. John/City Park area, Lakeview and Old Metairie. Growing up as a New Orleans Creole, my family always taught us that Creoles were local whites of French and Spanish colonial Louisiana ancestries, but they also acknowledged that there were also mixed race people that were Creoles as well and even some blacks that were Creole. So in other words, we saw and continue to see ourselves as Creoles but also recognize there are also other races of Creoles in Louisiana besides us. As in all the local born and raised people in Louisiana of a colonial Louisiana background.

Eric Fazende — November 27, 2021

Hello y’all I’m from Metairie, Louisiana (suburb outside of New Orleans) and my family moved here in the 1970’s from the city of New Orleans where our family had lived since they arrived from France in the 1700’s. I’m a Louisiana Creole of French descent (I’m a south Louisiana white person of French descent) and I’m proud to be so. I’ve read all the comments here and there are so many people that think they know what creole means and they tell it with such authority as if they are trying to teach you a fact rather than state it’s their opinion. Any they tell it as if their opinion is the only correct one. Well here’s something that I’ve studied up on by reading many historical accounts in Louisiana history that use the term creole:

1.) Creole is race neutral. It’s always been race neutral in Louisiana except for the late 1800’s when white creoles attempted to define it as white only and the mid 20th century until today where mixed race folks and others ignorant of its history attempt to define it as mixed race (mulatto) only and/or to be tied to being black. All through Louisiana history besides these two times that use a fraudulent claim, Creole has included white people, mixed race people and black people and the term creole is found in numerous historical documents to describe all these races.

2.) Creole always has been tied to meaning a native-born person to the land and culture, regardless of race or ethnicity. A synonym for a born and raised local person.

3.) Creole was also used to describe the local native-born culture in Louisiana (the one that mainly is found in stretching across south Louisiana today and has roots in the French and Spanish colonial periods of Louisiana). So please, no more of this cajun vs creole culture stuff because Cajuns are also creoles and the culture is way more than just cajun, so it’s all creole culture from one side of south Louisiana to the other. Just different styles of it based on region.

So these are the ways that creole has been used in historic Louisiana documents and thus, these descriptions are not opinions but are actual facts of history.

4.) Creole has also been used in regards to language and dialect as in a pidgin language composed of two languages or to describe a dialect of one language that has influences from other cultures.

These are the ways Louisiana history uses the term Creole. None of them specify one race or ethnicity is the only type of creole. And none of them specify any group adopted it from another group as it’s usage in Louisiana applied to all Louisianians, regardless of race since the invent of Louisiana as a colony and it’s first native-born generation.

Roy Villeré — August 19, 2022

I’m from southeast Louisiana and I’m a white person of full French descent, I’m a creole, actually the type of creole I am is known as “French Creole” (Louisiana white person of old Louisiana French descent). My last name is Villeré (from my father) which is very French Creole and my mother’s maiden name is Guillory and that is also very French Creole. My last name and my mother’s maiden name rhyme with each other. According to my paternal grandfather, I’m related to Louisiana’s first creole Governor (and second Governor after Louisiana became a US state) named Jacques Philippe Villeré, also a Louisiana French Creole. Hello to all Louisiana creoles!