Let’s say that you work in an office with several people, and everyone is expected to meet certain performance standards. You’re an outstanding performer, considered one of the best in the firm. A couple offices down from you is a guy named Wendel, and you feel sorry for Wendel because he’s not quite able to meet the performance standards and is always teetering on the edge of losing his job. Your sense of Wendel is that he’s a good guy who just never gets the right breaks, and if he were given more chances to succeed he could probably pull himself out of his slump.

One day, you’re working on a project team with Wendel and notice that he’s screwed up a major report bigtime—big enough that he’s sure to get fired if anyone else sees it—but so far only you have seen it and you have a brief opportunity to cover up Wendel’s mistakes. If you cover them up, in effect lying by passing off your work as Wendel’s, you’ll probably get away with it and Wendel will go on to work another day. If you don’t, he’s finished.

What will you do?

We normally associate acting dishonestly with causing harm to others, but it’s also quite possible that a dishonest act can help someone, like Wendel. Under what conditions we’re prone to act dishonestly to hurt or help another is what a new study in the journal Psychological Science investigated.

Researchers created a mock scenario in which study participants were randomly assigned to one of two roles: solver or grader. Each solver was also randomly assigned to a grader. Participants in both roles became either ‘‘wealthy’’ or ‘‘poor’’ through a lottery in which they had a 50% probability of winning $20. This lottery, together with the random pairing of solvers and graders, created four pair types: wealthy grader and wealthy solver; poor grader and poor solver; wealthy grader and poor solver; and poor grader and wealthy solver. After the lottery, solvers solved multiple anagrams. Graders then graded solvers’ work. Graders had the opportunity to dishonestly help or hurt solvers by misreporting their performance. If a grader overstated a solver’s performance, then the solver earned undeserved money. If the grader understated the solver’s performance, then the solver did not earn deserved money.

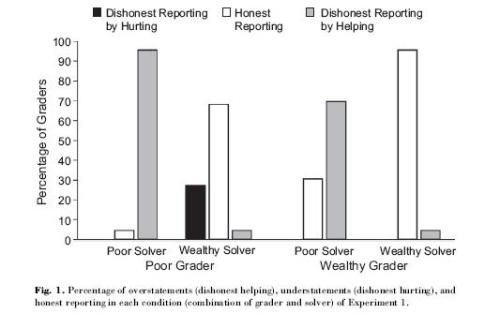

The results: When a wealthy grader was assigned to a poor solver, the grader overwhelmingly misreported the score to help the solver (about 70% of the time). When a wealthy grader was assigned to a wealthy solver, the grader nearly always reported the score honestly (90%). On the other side of the coin, when a poor grader was assigned to a poor solver, the grader nearly always misreported the score to help (95%). When a poor grader was assigned to a wealthy solver, however, the grader misreported the score negatively to hurt the solver about 30% of the time. A graph of the results is below.

The reasons for these results, the researchers surmise, are less about financial self interest and more about emotional responses to inequity. Individuals increase their dishonest hurting behavior and reduce their helping behavior when they are worse off than the other person. Conversely, they increase dishonest helping behavior when they are better off than the other person.

What we seem to be back to with this study is the realization that we’re not so rational after all. Dishonesty, in either direction, appears to be motivated by emotional reaction more than rational evaluations of self interest – at least in the context of relatively small sums of money (it would be interesting to see what would happen if we jacked the amount up a few hundred bucks).

So, not to forget about Wendel – how’d he make out in your mind?

Source: Gino, F., & Pierce, L. (2009). Dishonesty in the Name of Equity Psychological Science DOI: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02421.x

—————————-

David DiSalvo is a science and technology writer who regularly blogs at Neuronarrative and Brainspin on the True/Slant network. He is also a freelance writer for Scientific American Mind magazine.

If you would like to write a post for Sociological Images, please see our Guidelines for Guest Bloggers.

Comments 10

Lisa — October 17, 2009

One day, you’re working on a project team with Wendel and notice that he’s screwed up a major report bigtime—big enough that he’s sure to get fired if anyone else sees it—but so far only you have seen it and you have a brief opportunity to cover up Wendel’s mistakes. If you cover them up, in effect lying by passing off your work as Wendel’s, you’ll probably get away with it and Wendel will go on to work another day. If you don’t, he’s finished.

For me, this example scenario doesn't work. I do work in a large company, and if I find errors in another person's work, I help them understand and solve the errors asap. Because it's best for the team, and best for the company. It may help the individual in the short term, but that doesn't motivate me nearly as much as doing the right thing by the company I work for - e.g. presenting the correct information vs an incorrect report. How does that fit in to the presentation above?

Koeler — October 17, 2009

"we’re not so rational after all. Dishonesty, in either direction, appears to be motivated by emotional reaction more than rational evaluations of self interest"

The identification of self-interest with 'rationality' is part of exactly the paradigm that these kinds of experiments undermine. Historically it's been just as common to identify ethics with 'rationality', and it's at least arguable that class-solidarity (of which this shows perhaps a very very attenuated form) is rational.

Good post, obviously. Just commented because this sort of 'emotion vs. reason' set up is widespread and perhaps worth pointing out. Sorry if I'm a tool.

larry c wilson — October 17, 2009

My Grandmother and Mother called it a "little white lie." It is permissable to lie to HELP someone else, but it is never right to lie to help yourself. I think the RC Church still calls it a venial sin.

mike — October 17, 2009

maybe i just don't quite get it, but what about this is surprising?

Ranah — October 17, 2009

Is it really a response to inequity? What about a poor solver / poor grader?

In this case the grader lies to help the solver, thus creating inequity. It's something like "I can't be OK, let at least the other guy be OK".