Since George W. Bush became president, a common criticism of him and his presidency has been that of nepotism: that he only rose to prominence because he is a member of a distinguished, wealthy family that has been involved in politics for generations. In the 2000 election, both candidates were the sons of men who held high political office. When Hillary Clinton became a serious contender for the Democratic nomination, many people (including me) thought there might be something a little disturbing in the fact that we might be flip-flopping between two families for as much as 28 years (if she won two terms). It seemed like evidence that American politics is becoming increasingly exclusive, with family connections playing a huge role in who ends up in positions of power.

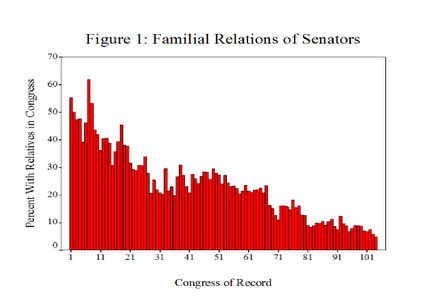

It is certainly true that family connections can have a lot of influence in U.S. politics. But Tom Schaller at FiveThirtyEight shows that, at least in the Senate, it’s becoming less common to have family members who also served in the Senate. Here’s a graph showing the percent of Senators in each Congress who had relatives who had served in Congress (at the same time or in the past):

The trend was clearly downward regardless, but Schaller points out that starting with Senators elected to the 64th Congress (in session 1915-1917), Senators were popularly elected rather than appointed. (Only 1/3 of Senators go up for re-election each time, so it wasn’t until the 66th Congress (1919-1921) that all serving Senators had been elected.)

So what we see is that in at least one part of the federal government, this particular type of family tie has decreased over time. Of course, there are many other ways family connections might help a person get elected to the Senate, and there are many other political offices that might be more or less influenced by a person’s family ties. If we looked at the percent of all Cabinet members, say, or Representatives, who had family members who had served in any major federal political position, we might see a much more obvious trend. But at the very least, the picture seems more complicated than arguments that our political system is dominated by a few family dynasties suggest.

The other thing that interests me is the fact that even Schaller seems to automatically equate having a family member previously (or currently) serve in the Senate with nepotism. I agree with a lot of his points about nepotism in general and the ways in which people often oppose “affirmative action” while never noticing the many, many ways they have themselves gotten an advantage from policies or personal connections that are, for all intents and purposes, forms of affirmative action. That said, nepotism as it is generally understood refers to people getting positions based on family connections regardless of whether they are qualified for or deserve them. I think Schaller is using the word in the looser sense of “getting a position based on family connections” without necessarily implying a lack of qualification. But I think for a lot of people, the fact that someone had a relative who previously served in high political office would be automatic evidence of nepotism (in the more derogatory sense) at play. And while I’m sure it often is, and that many people who get a job through family ties aren’t even vaguely qualified for them, I don’t know that showing that an official had a family member who previously held political office is prima facie evidence of nepotism. Presumably at least some people follow a family member into office and are completely and totally deserving of it, and thus might fit the less negative definition of nepotism I believe Schaller is using but not nepotism in the sense of “unqualified person who gets a job just because of Daddy.”

Comments 1

jfpbookworm — September 3, 2009

How does that track with the shift from legislatively appointed to popularly elected Senators?