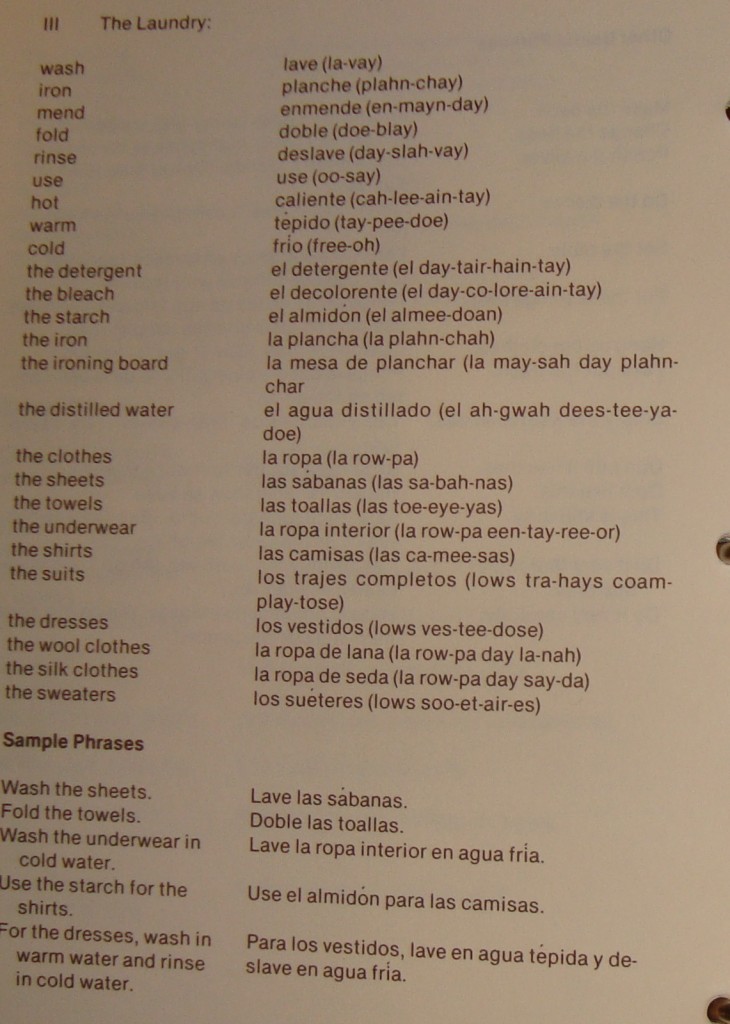

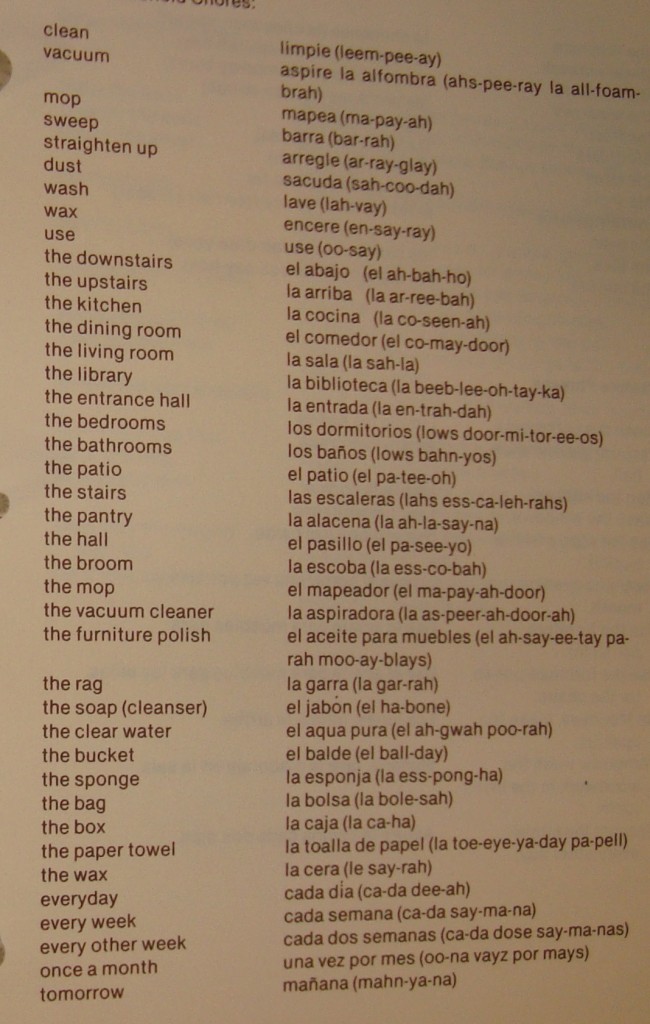

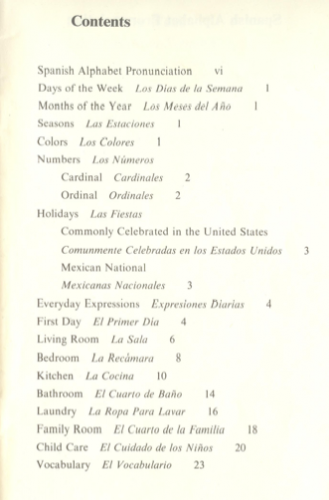

Mary M., of Cooking with the Junior League (go read it now! It’s awesome!) sent in photos she took of several pages from House Dressing, a cookbook published by the Windsor Square-Hancock Park Historical Society in 1978 (Hancock Park is a wealthy section of L.A.). The cookbook contains a section called “Kitchen Spanish,” which, as Mary says, “pretty much amounts to phrases you can use to boss around your help.” They are quite thorough, providing terms not just for cooking but for many other household tasks, and specific terms for wool vs. silk clothing. Here are images of a couple of the pages:

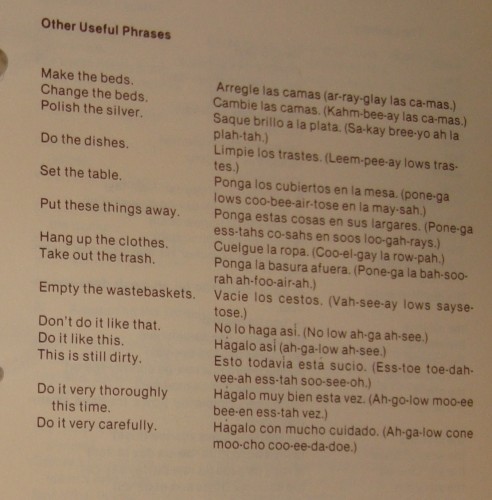

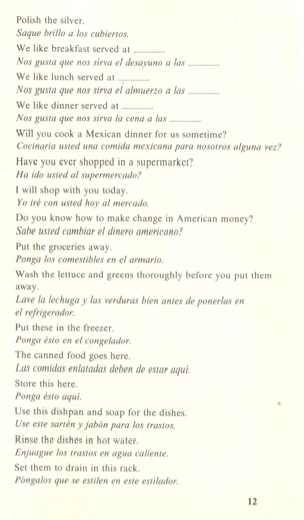

And here we have my favorites, “This is still dirty” and “Do it very thoroughly this time”:

And to think, when I first read the phrase “Kitchen Spanish” I assumed it was a geographically confused title for the Tex-Mex recipe section. Also, given that the pronunciation guides don’t include instructions on which syllable to emphasize, I can only imagine what kind of directions the employees actually received.

It made me think of the book Domestica: Immigrant Workers Cleaning and Caring in the Shadows of Affluence, by Pierrette Hondagneu-Sotelo. She discusses the tensions and conflicts that often arise between immigrant (largely Latina) housekeepers/nannies and their (mostly White and female) wealthy employers over how tasks should be done. Domestic workers generally expressed a wish to be told what to do, but not how to do it (and not watched while they worked), while employers felt they had to provide a lot of micromanagement if they wanted tasks done to their standards. Many instances where employees quit or employers fired them resulted from the conflict over this issue.

My guess would also be that many of the individuals contributing to and buying this cookbook would not be cooking anything from it themselves. The cookbook probably served as a form of symbolic domesticity for wealthy women to share recipes, while the women doing much of the actual cooking and cleaning in their households were present only implicitly as the recipients of the instructions on these pages. As Mary pointed out, something similar was probably true of all the “signature recipes” of First Ladies are often shown serving in photo ops–it seems likely that many of them had nothing to do with the preparation and may not have even supplied the recipe. Didn’t John McCain’s wife (I know, not a First Lady, but she was a hopeful) post a recipe on the campaign website that turned out to be taken from another cooking website?

NEW! (July ’10): Jason K. sent in another example, this one published in 1976:

Comments 20

Elena — August 4, 2009

Curiously, the translations use the respectful treatment of usted.

Also, given that the pronunciation guides don’t include instructions on which syllable to emphasize

Fortunately, Spanish is regular when it comes to stress: words where the stress fall on the last syllabe have an acento when they end in a vowel, N or S (cartón, estrés, café) and no acento when they do not (papel). Words where the stress falls on the last-but-one syllabe do it exactly the other way (agua, antes, andan, but árbol). And all the other words always have the appropriate accent mark (página, crítico, and so on). The translations up there have the acentos in their place...

Trabb's Boy — August 4, 2009

The whole concept of servants is very interesting, and I'll definitely check out that book you mention (Domestica, not the cookbook). There is a real sense among western liberals that hiring servants is somehow morally wrong, whereas in many countries, rich people feel a moral obligation to hire as many servants as they can afford.

When I dream about winning Powerball and think about buying a mansion, I always imaging lots of servants so I never have to cook dinner or make beds or pull weeds again. Then I think about not just paying the servants well, but making sure they and their families can live on the property if they want so they aren't stuck with a ridiculous commute and can take advantage of a better school system. Then I want to make sure that there are enough servants around so that they don't feel out of place in the rich community and eventually I just leave them all to live in the mansion and move myself out to the summer house by the pool and do my own cooking and cleaning and weeding. Liberal guilt runs deep.

Laura — August 4, 2009

Elena,

You pointed out that the commands are in the formal "usted" form, rather than the informal "tú" form. In my understanding, in most Latin American cultures, usted is used for almost everyone, and tú is reserved for close friends. Do you know how people generally talk to their servants? I don't know if the informality people use with friends would also be used with servants because of the power dynamic of the situation.

Dmitriy — August 4, 2009

is there a reverse dictionary as well. the one that would allow the maids/house cleaners/ nannies to communicate with the employers?

or are "the help" is expected to be seen and not heard.

p.s.

on related note, if there isnt one, what phrases should it contain?

Noir — August 4, 2009

The only thing I can think right now is that that spanish is incredibly awful. I can't even begin to say how awful it is. And the pronunciation? I understand you will pronounce different, but when books or whatever tell you to pronounce it wrong...

At least it explains the spanish I hear a lot from people whose native language is english.

Rachel — August 4, 2009

Sad, no phrases to say "That looks nice" or "Well done" or even "Thank you."

Elena — August 4, 2009

Laura, I speak Castilian Spanish, so I couldn't really comment on that. Treatment of usted is a lot more widespread in Latin America than here, though.

rachel — August 4, 2009

Wow...I can imagine that the people who really did use this guide to instruct their help got made fun of and laughed at behind their backs...not that they probably didn't deserve it...yes, i agree with the other poster, that spanish is horrible.

Carla — August 4, 2009

Elena and Laura -

as much as we'd like to think that they were being polite and using the "usted" form...they are not.

they are using "mandatos" in the "tu" form. so they are using a familiar way of giving commands.

they would most definitely NOT be using a respectful term when addressing "servants" or "help" as they so delicately put it. using the tu form of a command when it is not someone you are close with shows that you are of higher status, that you are more important, and more deserving of respect than the people you are addressing (which is why the tu form is often used when people are speaking to children - they are not old enough yet to have earned that respect)

Paulette — August 4, 2009

I agree with most of what Carla said. I also think that the instructions are given with "usted" because it is most teached than "tú" treatment, at least for what I have known.

I live in Chile and would like to tell Laura that here "tú" is being more used than "usted" nowadays, saving "usted" just for people you feel some kind of respect (seniors, sometimes proffesors). In the upper classes, children are taught not to use "usted" for older people, because parents feel it is sort of "lower class thing" (everything here is about class, I guess).

And last, the book contains a lot of misspellings, like "agua distillado", when it should say "agua destilada" and many more. Shouldn't be a book check many times, by people who can really understand? I work as a proofreader and surely be fired for that.

Elena — August 5, 2009

Carla: "as much as we’d like to think that they were being polite and using the “usted” form…they are not.

they are using “mandatos” in the “tu” form"

Mmm... no? It's "lave/planche/limpie (usted)" and similar sentences throughout, not "lava/plancha/limpia (tú)".

opminded — August 5, 2009

I support books that make it more likely that someone in America who speaks no English can find employment. Isn't that a good thing?

Larry — August 6, 2009

My most amazing such experience: Seeing the Spanish phrase (which I have forgotten) for: "Sharpen the blades on your mower."

Sighter — August 7, 2009

My only spanish was high school AP stuff and a semester of it in college, but I do remember we were never taught any command verb tense other than the one used in the book. If there is a "usted" or "tu" distinction in giving commands, I guess I just don't recall learning it.

I think the mere fact that it's conjugated FOR people to read it as a command is the telling part, anyway. I mean, they don't EXPECT you to learn spanish. You just put the words together it gives you, and the book writers ASSUME you will be using it to issue orders.

Bea — August 7, 2009

As a native Spanish speaker and a Spanish Language major, I have to say that the Spanish there is rather horrible ("tepida"? did they get that from a XIX century novel? it's "tibia"!), and an open invitation to be mocked by the help.

And I agree with Sighter and Dimitry and Rachel. The most disturbing things are the imperative mood, the absence of any positive comments, and the lack of a reverse dictionary. That last one is even functionally illogical. How are you supposed to understand when your maid tells you you're running low on detergent, furniture polish and vacuum bags?

And a brief note about tú/usted in Latin America. Laura is right, its use is frequent in the Americas, and, further, it varies from region to region.

In Colombia, for example, usted denotes warm admiration, and so it is used for people close and important to you. Tú is for everyone else.

In Mexico, the country of origin of most domestic employees in L.A. (as well as mine), usted can imply some respect, but mostly it implies distance. You use tú with your equals and usted with everyone else. With figures of authority, or people otherwise "above" you in some hierarchy, you use it to show respect. With those "below" you, you use usted to implicitly demand that they respectfully address you as such, to make a point about your inequality.

Lately, many people in Mexico that would traditionally be adressed as usted -professors and bosses- are not demanding the pronoun anymore, and some even ask that you call them tú. Well, at least if you're a middle class student or a college-educated professional. This doesn't seem to stick when there are class differences, so even within Mexico, domestic employees get told "lave, barra, planche".

Sandrágoras — August 18, 2009

I agree with Bea: the Usted implies distance, but I Live in Mexico City, in a middle class medium size house, and the cleaning lady that helps us is older (50-52 years old, I think) and we address to her as "Usted", adding a "Por favor" (please) and "Gracias" (thank you). The requests are in question form, like: "¿Podría trapear la cocina?" (Can you mop the kitchen floor?). I don't know if the help staff gets the same treatment in all homes in Mexico, but as far as I know, you just can't address an older person with the TÚ, even if she or he is your subordinated. As a matter of fact, the lady uses the TÚ to address me :) , but that is because I'm younger than her.

K — August 1, 2010

I have a very similar book, except it uses Hawaiian rather than Spanish. The text was originally published around 1920. However, my copy is a new edition that was billed as a "Hawaiian phrasebook," with no mention of servants on the cover.