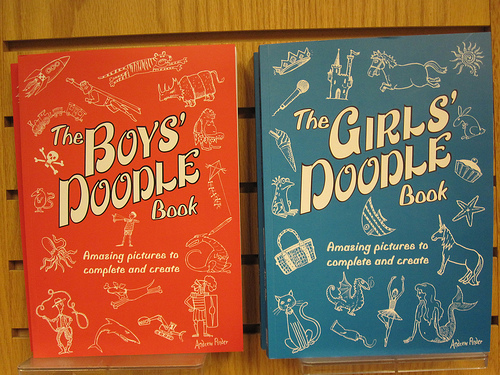

Eric Stoller sent us a photo he took at Borders recently of two doodle books, one targeting boys and one targeting girls:

In Eric’s post about the books at his blog, he says,

The Boys’ Doodle Book features the following images on its cover: triceratops, ogre, tiger, superman, rocket, skull & crossbones, octopus, boy w/slingshot, mouse, train, kite, dragon, knight, shark, excavator, dog and a cowboy.

The Girls’ Doodle Book in comparison has a different cover color and a variety of differing images than the Boys cover including: crown, pony, castle, sun, microphone, ice cream cone, frog/prince, purse/bag, rabbit, cupcake, starfish, unicorn, fish, cat, toothpaste, dragon, ballerina and a mermaid.

I’m surprised that the Girls’ Doodle Book didn’t have a pink colored cover given the overall stereotypical and gendered nature of the doodles on the cover. Boys like fire, machines, spikes and death, while Girls like food, animals typically associated with non-violence, dancing/arts and hygiene. I’m not saying that there is anything inherently wrong with any of the doodles. What I am saying is that gender-based stereotypes are being perpetuated in overt contrast with these two books.

Thanks for sending the image along, Eric!

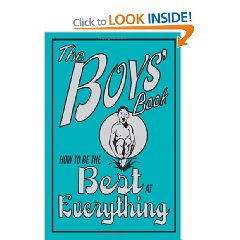

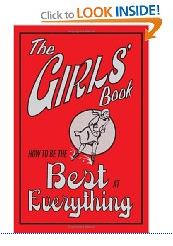

NEW! Laurel O. found another example, the Girls’ and Boys’ versions of How to Be the Best at Everything:

Laurel’s kids’ school sent home an order form for books. The descriptions of these two:

The boys’ book description says “Learn how to lasso like a cowboy, juggle one-handed and more” whereas the girls’ book says “Design your own clothes, host the best sleepover, and lots more.”

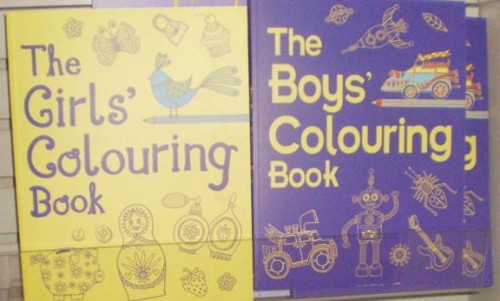

NEW! (July ’10): Gaby K sent in an example of British coloring books aimed at boys and girls. We see a lot of the typical gendered stuff: girls like cupcakes and perfume and butterflies, while boys like trucks and bugs and rockets. Gaby also points out that the girls’ version has a passive Russian nested doll while the boys’ has a robot with apparently movable joints:

Comments 35

SarahMC — June 4, 2009

Is that toothpaste on the girls' book?!

Trabb's Boy — June 4, 2009

The books are probably trying to leech some of the interest generated by that Dangerous Book for Boys that came out a few years ago. They have the same retro font and a number of the pictures, especially on the boys' one, are of interests boys stereotypically had in the '50s.

It's interesting that they included a dragon on the girls' version, but that it is a cute, friendly dragon compared to the vicious one on the boys'.

And yes, that does look like a tube of toothpaste. Uh...

Kelly — June 4, 2009

Currently, I'm an art student training to be an illustrator. Images like these only serve to remind me that as an aspiring illustrator is very important to keep in mind how the drawings I make might help to challenge or reinforce social stereotypes. Of course, you can't always have complete control over the final image, depending on what the client wants, but you can at least control what types of jobs you take on.

me — June 4, 2009

I think the "toothpaste" is a tube of paint!

Dusk_Blue — June 4, 2009

Looks like an old-fashioned set of gendered colors: red as the bold passionate masculine, and blue as the mild tranquil feminine. I'd say it's better than the now typical blue and pink in that the colors are non-standard and would probably have less of the same effect in today's society. Obviously not ground-breaking, though.

Duran — June 4, 2009

Is Eric suggesting that the boys' book would sell better if it included unicorns and ballerinas? And that the girls' book would sell better if it included excavators and rockets?

Have you guys ever thought that perhaps industries reinforce the stereotypes because that's what people want, as evidenced by their willingness to spend money on products?

It would be great to have every poster to this blog take ECON 101.

Vidya — June 4, 2009

It would also be great if Duran would take a social theory course on the constitution of subjectivity. Or even a marketing psychology course, for that matter.

Eric Stoller — June 4, 2009

@ Duran - People want what they have been socialized to "want. Industry perpetuates patriarchal stereotypes and covertly showcases sexism.

And, FYI, I did take ECON 101 and completed a minor in marketing during my undergrad career...

Eric Stoller — June 4, 2009

PS: Those who have power a.k.a. the dominant paradigm purveyors of patriarchy create institutionalized defined norms. It is these defined norms (not create by those in marginalized groups) that artificially create the desire to purchase something. E.g. Why would most men not purchase a pink cellphone? They have been socialized that a pink device is anti-masculine. This comes from patriarchal socialization and not from some sort of inherent individual desire.

Maggie — June 4, 2009

@Eric

"Industry perpetuates patriarchal stereotypes and covertly showcases sexism."

I completely agree. The reason for the gender distinction in these doodle books is not due to "economics." A gender-neutral doodle book could've probably been made without a significant blow to sales (and production would probably be cheaper anyway, since you wouldn't need to produce two different books with different color schemes/designs/topics).

Creating unnecessary gender distinctions in children's toys is socially harmful, as the message that girls and boys are radically different becomes reinforced again and again. And since traditionally the distinction has been male=norm, female=inferior, sexism continues.

*I* think it'd be great if every reader would take the time to educate themselves on the basics of patriarchy before commenting. Google for this great resource: Finally, A Feminism 101 Blog.

Samantha — June 4, 2009

You can search inside the books on Amazon. Strange, there, the book for boys is blue and the book for girls is red.

Girls:

http://www.amazon.co.uk/gp/reader/1906082227/ref=sib_dp_pt#reader-link

Boys:

http://www.amazon.co.uk/gp/reader/1906082235/ref=sib_dp_ptu#reader-page

Excerpts from the girls' version instruct them to draw flowers, animals ("Draw each dog a designer outfit") and a cake, while the boys' tells them to draw a robot, aliens, a viking shield and a cowboy horse.

Looks like the girls got the short end of the stick.

Ellen — June 4, 2009

I honestly don't think Duran really gives a shit. He comes here to let us all know how stupid he thinks we are. He himself most likely never took an econ 101 class. If he had he would know that most of economic theory doesn't really hold up in society. Especially since advertising has gotten a hold of psychology. Some major ones would be that people make rational, individual choices with all of the necessary information. Yeah right.

Oh, and Dusk Blue is right. Those were the gender normative colors before 1930.

Ellen — June 4, 2009

I don't know why someone with no sociological imagination would frequent a sociology blog unless it is to be contrary for the sake of being contrary. And we respond and give him the argument he is looking for every time.

Ellen — June 4, 2009

And the other option to this does not have to be giving boys unicorns and girls excavators. Believe it or not, girls and boys enjoy more similar activities than different.

Trabb's Boy — June 4, 2009

Duran is being argumentative, but he has a point. Hang out with a bunch of lefty moms, and you'll hear a lot of lamenting about their children's stereotyped interests. If I had a nickel for every time I heard the joke about it being obvious that a male invented the wheel ...

There probably are some innate differences, that aren't inevitable sex-linked traits, but which show up in larger proportions in boys or girl. It seems likely that a larger percentage of boys find speed and aggression pleasurable and a larger percentage of girls find social interaction and nurturing pleasurable. The problem with marketers glomming onto this is that it is a stereotype. The bell curve for boys' innate interest in aggression may be skewed further to the right than girls', but that doesn't mean in the slightest that "aggression" is male and is not female.

Manufacturers glom onto stereotypes, however they are derived, for economic reasons. If 40 percent of young boys prefer cars, 30 per cent prefer sports, 10 percent prefer fighting games, and the other 20 percent are divided among fifty different types of toys, it's cheapest to focus on the cars, sports, and fighting games. Not only does it provide a more predictable return, but it reinforces the stereotypes, which might push boys' interests further onto those few items, creating greater returns, etc.

So it is economics, but it's still sexist and damaging to society.

Girls Like To Draw Hygiene [Drawing Conclusions] by Funny Celebrity . info — June 4, 2009

[...] Posted by Deusdies as General The message of these Girls’ and Boys’ Doodle Books, according to Eric Stoller: “Boys like fire, machines, spikes and death, while Girls like food, animals typically associated with non-violence, dancing/arts and hygiene.” [Eric Stoller, via Sociological Images] [...]

Less Optimistic — June 4, 2009

I'd be interested in how many of those certain that children are molded into stereotypical roles by what they learn from society actually have children. I have a boy and a girl and my wife and I were fairly certain that we were going to raise our children to be free from social brain washing. We limited TV to almost nothing and were very careful about what they did watch. Being in a less than ideal neighborhood, we raised them without much interaction from other children and any interaction was supervised. Family members were carefully instructed on what was acceptable gifts so we wouldn't imprint them with any marketing imaging. We got our son a baby doll. Our daughter was handed down the same toy tools that our son had as a child. And what do we have?...A boy who loves frogs, slingshots and space rockets and a little girl who will only wear pink and wants to be a princess. I know this is an sampling of one and we might have missed somethings that they saw somewhere but I have to say that I tend to agree with some of the newer studies on nature vs. nurture that point more toward biology as an indicator of our future than nurture. I now believe that boys and girls are more different by nature than many of us these days want to give credit to. But thats just me...

Kelly — June 4, 2009

'Speaking from a purely personal and anecdotal level, I really hated all of the traditional "girl" toys as a child and always felt like I was getting the short end of the stick, especially with the toys in the McDonald's Happy Meals. I would cry and complain until they gave me a car instead of a princess.

weliveunderrocks — June 5, 2009

While in my experience it's mostly true that somehow little girls seem to go more for dolls and boys for cars (I say mostly cause I was heavily into matchbox, my brother stole my sisters dolls, and my nephew loves his mummy's pearl necklace and insists on wearing pink socks… ok, he's 4), I still wonder why marketers feel they have to gender toys in such an obvious way at all.

Is there a selling benefit in dividing all toys into male and female categories by colour code? Why can't we have pirate ships, princess castles, building blocks and colouring books presented in a more neutral fashion? It might make some girls feel more comfortable demanding the ship and some boys asking for the castle. Which should elevate sales, not reduce them? Or am I missing econ 101 now?

And anyway, who ever came up with the idea that there was a 'correct' way to play with stuff, or a 'feminine' and 'masculine' way of playing? I'd have attacked the princess castle and abducted the princess same as I shaved my Barbies a mohawk (and no, I wasn't into rough'n'tumble play with the boys – I just was). And my nephew has a pirate ship and makes the pirate trade goods and go shopping (they look as if they could use some new clothes). Seems fair to me.

Endor — June 5, 2009

"I know this is an sampling of one and we might have missed somethings that they saw somewhere but "

Like peer pressure in school for example? Or simply walking through the mall with you kids. What about Halloween costumes - might they have noticed what boys dress up as and what girls dress up as? Do you think they didn't notice the gender divisions in the toy section at Wal-Mart? Kids are not dumb - they are little learning machines. No one can keep them entirely free from society's influence.

I find it deeply interesting that "it's just biology" is ALWAYS used to justify sexism.

Fred Goodwin — June 5, 2009

Google vervet monkey study to see if there are any innate differences between males and females in their attraction to gender-typed toys.

b — June 5, 2009

I tend to agree with some of the newer studies on nature vs. nurture that point more toward biology as an indicator of our future than nurture.

The studies I've seen on the subject don't say this - they say that it's a much more complex interplay than could possibly be captured by the phrase "nature vs nurture."

Take identical (monozygotic) twins raised apart, who don't meet until adulthood. They are frighteningly, creepily similar. They tend to wear the same type of clothes, have the same careers, marry very similar people, have the same hobbies and even the same annoying little habits. It really is almost as though the same person was out there existing twice in the world.

Proof positive that it's all biology, right? UNTIL you add in the fact that MZ twins raised together are nothing like this. Sure, they often have more similar personalities than regular siblings, but they are very distinct people in many ways. Being raised with a twin has caused them to specifically push away from being exactly like their sibling, resulting in two very distinct and different people with the same DNA. Nurture had every bit as much to do with their eventual personality and choices as nature did.

To deny the effects of biology is completely foolish, and yes, I'm sure that there are biological differences between males and females (I mean, at a bare minimum there are obvious hormonal differences which must have neurological implications). But to say that biology trumps environment is just as foolish, and oversimplifies matters way too much.

Ellen — June 5, 2009

First, there is no nature vs. nurture. It's an interaction. You can't separate the two. But if you really read the research on sex differences, not a random article interpreted by mass media on vervet monkeys, you will find that there is much more variability and overlap among the sexes than between the sexes. The problem with scientific research in general is the goal is to find significant differences. If no differences are found then the research doesn't get published. This has been very much the case with gender research. And many of the studies that refute some of the preliminary research that has found differences gets published, but the media finds it boring, so it doesn't get reported on. One of the really interesting thing about the observational research on primates is that once women started entering the field and observing the primates, the observations became very different and no longer reinforced gender stereotypes.

@ Less optimistic: You were born in this world, you will never be able to see every way you have been influenced and not only keep yourself from influencing your children but the rest of society from influencing them as well.

One of my best friends thinks it is just so amazing that her son always wanted to wear the clothes that had sports appliques on them. Of course, he was getting a choice between a sports applique and plain. Not a choice between a sports applique and a flower.

Joanne — June 6, 2009

Interesting discussion. I have to say that while the images geared toward each gender are disturbing, I was especially shocked to see a frog with a crown on its head for the girls. This is 2009...should we really be telling little girls that they need to find their frog prince to rescue them? Ridiculous.

Shae — June 10, 2009

It's interesting that you should mention what "kinds" of animals girls like.

My husband and I recently noticed the gendered quality of animals associated with home decor.

Women fill their home spaces with animals that you nurture: cats, geese, cows, pigs, chickens.

Men fill their home spaces with animals that you kill: deer, ducks, fish. Dogs are included because they help you hunt.

2becontinued — June 13, 2009

When I was a kid, I drew dragons and dinosaurs A LOT (I still have my doodle-filled notebooks to prove it), also, I'm a girl. I know that's anecdotal and all, but seriously, the blue book would not appeal to me at all when I was a kid (well, maybe the mermaid one would have).

Also, as a person who works retail, I've noticed several times that when a child picks a toy that isn't for their gender, especially if it's a boy picking a 'feminine' toy, the parent will tell the child to pick another toy because it's the "wrong one." It annoys the hell out of me.

Sociological Images » My Pretty Princess Purse — June 25, 2009

[...] here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, and here. tags: children/youth, gender, toys| Permalink| Media Coverage of Uighurs in Bermuda [...]

Merle — August 29, 2009

Readers of this essay may well ask what an academic psychologist is doing invading territory normally reserved for scholars closer to C. S. Lewis’s own field of literary criticism or for theologians

and philosophers. The short answer to that question is that Lewis had a lot to say over his lifetime about three topics of interest to me: science, social science, and gender. The longer answer to that question is more autobiographical.

In my Canadian Protestant childhood—as in C. S. Lewis’s, a generation earlier in Protestant Belfast—church was still a vehicle of respectability and upward mobility, perhaps especially for my parents,

who were schoolteachers and first-generation urban transplants from humble rural backgrounds. In such a setting, it was expected that teenagers would be confirmed in the church, but it never was made very clear how seriously—other than as a rite of social passage—they should take the professions of faith they were urged to make. Predictably, this led to resistance and accusations of hypocrisy from some adolescents, including myself, as I vacillated between thinking that church membership would demand too much of me and suspecting that it would demand too little.

But in the end, like the adolescent

C. S. Lewis, “I allowed myself to be prepared for confirmation, and to make my first Communion... eating and drinking to my own condemnation” (Lewis 1955, 130), metaphorically crossing my fingers behind my back while going through the motions of professing faith.

You will not be surprised to learn that such superficial churchianity did not survive—either intellectually

or morally—my transition from high school to an elite public university. I had wanted to study psychology ever since my middle-school days, but by the time I entered university in the early 1960s, academic psychology was suffering from what might be called a bad case of physics envy. In its eagerness to be accepted as a legitimate “science” it had embraced what philosophers call the Unity of Science thesis—namely, that there is only one method that all genuine sciences employ, and that method consists of giving causal, deterministic explanations that are empirically testable. By this standard, if psychology aspired to be a “real” science it would have to become as much like experimental physics as possible. As a methodological corrective to certain past, ill-supported pronouncements about human behavior and mental life (including many from Freudian and Jungian psychoanalysis) this was not an entirely bad move, but methodological correctives seldom stay within their original limits. They more often become full-blown—but usually unacknowledged—metaphysical world views, especially in times of great social change when older belief systems are being unreflectively marginalized in the name of progress.

This is in fact what was happening during my undergraduate days. We were being taught as apprentice logical positivists to regard “facts” and “values” as quite distinct. Facts—based on input

Trinity 2007

Opposite Sexes or Neighboring Sexes?

C.S. Lewis, Dorothy L. Sayers, and

the Psychology of Gender

Mary Stewart Van Leeuwen

And in that volume Lewis made both an Aristotelian and a Freudian argument for male headship in marriage.

Both Aristotle and Freud held that women were driven more by emotion and less by reason than men. For Aristotle (and his later Thomistic followers in medieval Christendom) all things exist in a hierarchical

scala naturae, or “ladder of nature,” beginning with inanimate matter and proceeding through plants, animals, humans, and ultimately the “unmoved mover” that gives all objects their purpose. But on the human part of the ladder, women occupied a lower rung: in relation to men they were deemed less rational, unequal, and passive. For Freud also, “anatomy is destiny.” He saw women even in adulthood

as having less-developed superegos than men, and hence less capable

A Residual Platonism

Years later, when I returned to Lewis’s works as a young Christian academic, I confirmed that for much of his life he did indeed promote both an essentialist and a hierarchical view of gender. He regarded stereotypical masculinity and femininity as timeless, metaphysical archetypes, deeper even than biological sex and apparently more significant for the right organization of social life than any “mere humanity” shared by women and men. Moreover, especially in his Preface to Paradise Lost (1942) and in Perelandra (1942) and That Hideous Strength (1945), the second and third novels respectively

of his space trilogy, he portrayed God as representing the highest ideal, or form, of masculinity. For the Lewis of the 1940s, humans were so inescapably gendered—in their creation, their fallenness, and the implications of their redemption—that man and woman were almost different species. They were metaphysically opposite sexes, not the “neighboring sexes” that his contemporary, Dorothy L. Sayers, proposed in one of her own essays in the 1940s (Sayers 1975, 37).

Thus in his 1945 science fiction novel, That Hideous Strength, Lewis (speaking through the trilogy’s

hero, Elwyn Ransom) asserted that:

Gender is a reality, and a more fundamental reality than sex. Sex is, in fact, merely the adaptation to organic life of a fundamental polarity which divides all created beings. Female sex is simply one of the things that have feminine gender; there are many others. Masculine and feminine meet us on a plane of reality where male and female would be simply meaningless. Masculine is not attenuated male, nor feminine attenuated female. On the contrary, the male and female of organic creatures are rather faint and blurred reflections of masculine and feminine

(Lewis 1945, 314–315).

Lewis’s residual Platonism is very evident here. He regarded the eternal, metaphysical “forms” of masculinity and femininity as higher spiritual realities of which material maleness and femaleness are mere “shadows,” a Platonic term Lewis used often to describe the earthly in comparison to the heavenly.

And for the younger Lewis, these polarized forms were not merely Platonic opposites; they were also hierarchically ordered.

In his 1948 essay arguing against opening the Anglican priesthood to women, Lewis wrote that a woman can be a competent pastoral visitor, church administrator, or even a preacher. It is not the case that she is “necessarily or even probably stupider than a man” (Lewis 1970a, 235). What she cannot do, wearing the “feminine uniform,” is sacramentally represent the people of God at the Eucharistic altar, because God represents ultimate masculinity, beside whom everything and everyone is less masculine and more feminine by contrast. Lewis wrote:

To say that men and women are equally eligible for a certain profession is to say that for purposes of that profession their sex is irrelevant... This may be inevitable for our secular life. But in our Christian life we must return to reality... the kind of equality which implies that equals are interchangeable (like counters or identical machines) is, among humans, a legal fiction. It may be a useful legal fiction. But in the church we turn our backs on fictions. One of the ends for which sex was created was to symbolize for us the hidden things of God... [Thus] only one wearing the masculine uniform can... represent the Lord to the Church; for we are all, corporately and individually, feminine to Him. (Lewis 1970a, 237–38)

Escaping the Sword between the Sexes

Even more, “the misogyny of some of Lewis’s earlier works seems to be reversed in this novel told from a woman’s perspective” (Hannay 216). Its story is a recasting of the classical myth of Cupid and Psyche which, in Lewis’s adaptation, focuses on the strong woman ruler of a small nation. She is a person struggling against idolatry and toward belief in a way that parallels Lewis’s own faith journey and the resentment it inspired in some of his colleagues and family members.

This period also coincided with Lewis’s work on The Discarded Image (1964), an introduction to medieval and Renaissance literature. It is an engaging, detailed portrait of the medieval worldview and one that clearly illustrates its hierarchical cosmology, but with one significant difference. In a volume where one would expect Lewis, given his earlier writings, to include an exposition of gender hierarchy

in the Aristotelian ladder of nature and its descendent, the medieval “great chain of being,” there is not a word on this topic. Indeed, his only explicit mention of gender relations was a leveling one, when he challenged the modern illusion that medieval persons of both sexes led static lives. On the contrary, Lewis wrote, “Kings, armies, prelates, diplomats, merchants and wandering scholars were continually on the move. Thanks to the popularity of pilgrimages, even women, and women of the middle class, went far afield; witness the Wife of Bath [in Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales] and Margery Kempe” (Lewis 1964, 143). Kempe was a fifteenth-century religious mystic who was also married and the mother of fourteen children.

Most telling is his reflection on his wife’s death, A Grief Observed (1961). It was written when Joy Davidman—an award-winning American poet and writer—died of cancer in 1960 after just four years of marriage to Lewis. The start of Lewis’s friendship with Davidman (in the early days of which he once referred to her as “our queer, Jewish, ex-Communist American convert…” In Lewis 2007, 450) coincided with his 1954 move from Oxford to a professorial chair at Cambridge. This move coincided with his first serious bout of writer’s block. It was due largely to Joy Davidman’s help and inspiration that he eventually wrote Till We Have Faces, which he then dedicated to her. Lewis’s biographer and former student, George Sayer, who knew them both well, noted that “[h]er part in the book, and there is so much that she can almost be called its joint author, put him very much in her debt. She stimulated and helped him to such an extent that he began to feel that he could hardly write without her” (Sayer 220).

“There is,” Lewis wrote in A Grief Observed, “hidden or flaunted, a sword between the sexes till an entire marriage reconciles them” (Lewis 1961, 40). In a pointed rejection of his earlier insistence that gender, as a spiritual ideal, is a more fundamental reality than sex, Lewis concluded:

It is arrogance in us [men] to call frankness, fairness and chivalry “masculine” when we see them in a woman; it is arrogance in them [women] to describe a man’s sensitiveness or tact or tenderness as “feminine.” But also what poor, warped fragments of humanity most mere men and mere women must be to make the implications of that arrogance plausible. Marriage heals this. Jointly the two become fully human. “In the image of God created he them.” Thus, by a paradox, this carnival of sexuality leads us out beyond our sexes. (Lewis 1961, 40–41).

As he struggled with his grief and reflected on what he had learned from his short-lived marriage, Lewis also reversed his earlier assumptions about gender hierarchy as well as his view that women and men could not be both friends and lovers at the same time:

A good wife contains so many persons in herself. What was [Joy] not to me? She was my daughter and my mother, my pupil and my teacher, my subject and my sovereign; and always, holding these all in solution, my trusty comrade, friend, shipmate, fellow soldier. My mistress, but at the same time all that any man friend (and I have had good ones) has ever been to me... Solomon calls his bride Sister. Could a woman be a complete wife unless, for a moment, in one particular mood, a man felt almost inclined to call her Brother?

(Lewis 1961, 39–40)

Clearly Lewis’s marriage in his mid-fifties to a gifted and feisty woman helped to advance changes in his thinking about gender relations. And, in fact, Lewis was always a better man than his theories in his actual relationships with women, especially those who, like himself, were intellectuals and serious Christians. I note in passing his long association with Stella Aldwickle, pastoral advisor to the women students of Somerville College. He also corresponded for twenty-five years with an Anglo-Catholic nun, the theologian Sister Penelope Lawson (whom he referred to as his “elder sister” in the faith), and for the last fifteen years of his life had a mutually-mentoring relationship with the celebrated and much-honored English poet Ruth Pitter.

The Cresset

C. S. Lewis and Dorothy Sayers

But Lewis had an equally long relationship with a woman colleague who was even closer to him in terms of age, background, education, intellectual interests, and Christian writing projects. That woman was Dorothy Leigh Sayers, whom Lewis once described as “the first person of importance who ever wrote me a fan-letter” (Lewis 2007, 1400). Sayers, like Lewis, grew up in the shadow of an Anglican rectory. By the time of their first correspondence in 1942 she was, like Lewis, an Oxford MA. Both had won scholarships to Oxford as undergraduates: Sayers to Somerville College in 1912, and Lewis to University College in 1916. She was also, like Lewis, a published poet, author of several novels in a popular new genre (detective novels in her case, science fiction in Lewis’s), and a BBC broadcaster recruited to help strengthen Christian faith in the dark days of World War Two (doing radio drama in her case, popular theological talks in Lewis’s). Sayers also had written and directed two plays for the Canterbury Cathedral arts festival, published essays on Christian doctrine and creativity, and was soon to become a distinguished translator of Dante’s Divine Comedy from Italian into English verse.

Though most of their correspondence was of a scholarly, literary-critical nature, some of it also concerned gender relations. For example, in 1948, when Lewis became exercised about the possible ordination of women in the Anglican church, he tried to persuade Sayers—a well-known Christian author of longer standing than he—to join him in protest (Lewis 2004b, 860). However, Lewis’s attempt to co-opt this famous woman writer backfired. Though Sayers was, if anything, even more Anglo-Catholic in her leanings than Lewis, she politely declined to “give tongue” in the debate over women’s ordination. She agreed that it might “erect a new and totally unnecessary barrier between [Anglicans] and the rest of Catholic Christendom,” but she pointed out that it would also decrease differences with those Protestant free churches that emphasized preaching more than the sacrament of communion (Sayers quoted in Reynolds 359).

In some ways it would be too simple to call Sayers a feminist. Like Lewis, she had too robust a view of the human capacity for sin to romanticize any class or gender group just because it had a history of marginalization. But unlike the Lewis of the 1940s, she believed gender was an incidental, not an essential trait, and that women and men’s common humanity was more fundamental than any differences

between them. Moreover, despite sharing a common background with Lewis in terms of class and intellectual brilliance, Sayers went through a species of baptism by fire at Oxford that Lewis, as a privileged male student and later an Oxford don, was quite incapable of understanding at the time. It was only two years before Sayers went to Oxford in 1912 that the university officially had recognized the presence of women in its midst. When Sayers arrived in 1912, women still could not receive Oxford degrees, even after meeting all the qualifications and (not infrequently) outperforming men in the same programs. Only in 1920, when Oxford degrees were retrospectively opened up to females, did Dorothy Sayers and several hundred other women return to the university to receive their long-denied degrees.

In 1927 the faculty and administrators at Oxford voted to limit indefinitely the number of women students who could be admitted and to prohibit the establishment of any more women’s colleges. Lewis supported this proposal (Lewis 2004a, 702–3). Though Lewis and Sayers did not know each other at this time, her reaction to Oxford’s retrograde move was pretty clear. Her most complex detective novel (and her own favorite) was Gaudy Night, which she set in a fictitious Oxford women’s college in the mid-1930s. The plot of the novel turns on the resentment that tradition-bound male academics—and their female supporters—harbor towards women scholars whose commitment to intellectual integrity will not be compromised by submission to social norms about women’s “natural calling” to support and defer to men, no matter what they do (Sayers 1935). Later, in her 1946 essay “The Human-Not-Quite-Human,” she mocked the view (going as far back as Aristotle) that women are not complete persons:

[People believe women] lie when they say they have human needs: warm and decent clothing; comfort on the bus; interests directed immediately to God and his universe, not intermediately

through any child of man. They are [either] far above man to inspire him, far beneath him to corrupt him; they have feminine minds and feminine natures, but their mind is not one with their nature like the minds of men; they have no human mind and no human nature... They are “the opposite sex”—(though why “opposite” I do not know; what is the “neighbouring sex”?). (Sayers 1975, 32)

“I do not know what women as women want,” Sayers declared in a 1938 lecture. “But as human beings they want, my good man, exactly what you want yourselves: interesting occupation, reasonable freedom for their pleasures, and a sufficient emotional outlet. What form the occupation, the pleasures,

the emotional outlet may take depends entirely on the individual. You know that this is so with yourselves—why will you not believe that it is so with us?” (Sayers 1975, 17–36, quotation 32).

Gender and Modern Social Science

C. S. Lewis was no fan of the emerging social sciences. He saw practitioners of the social sciences mainly as lackeys of technologically-minded natural scientists, bent on reducing individual freedom and moral accountability to mere epiphenomena of natural processes (See Lewis 1943 and 1970 b). And not surprisingly (given his passion for gender-essentialist archetypes), aside from a qualified appreciation

of some aspects of Freudian psychoanalysis (See Lewis 1952 (Book III, Chapter 4) and 1969). “Carl Jung was the only philosopher [sic] of the Viennese school for whose work [Lewis] had much respect” (Sayer 102).

But the social sciences concerned with the psychology of gender have since shown that Sayers was right, and Lewis and Jung were wrong: women and men are not opposite sexes but neighboring sexes—and very close neighbors indeed. There are, it turns out, virtually no large, consistent sex differences in any psychological traits and behaviors, even when we consider the usual stereotypical suspects: that men are more aggressive, or just, or rational than women, and women are more empathic, verbal, or nurturing than men. When differences are found, they are always average—not absolute—differences. And in virtually all cases the small, average—and often decreasing—difference between the sexes is greatly exceeded by the amount of variability on that trait within members of each sex. Most of the “bell curves” for women and men (showing the distribution of a given psychological trait or behavior) overlap almost completely. So it is naïve at best (and deceptive at worst) to make even average—let alone absolute—pronouncements about essential archetypes in either sex when there is much more variability within than between the sexes on all the trait and behavior measures for which we have abundant data.

This criticism applies as much to C. S. Lewis and Carl Jung as it does to their currently most visible descendent, John Gray, who continues to claim (with no systematic empirical warrant) that men are from Mars and women are from Venus (Gray 1992).

And what about Lewis’s claims about the overriding masculinity of God? Even the late Carl Henry (a theologian with impeccable credentials as a conservative evangelical) noted a quarter of a century ago that:

Masculine and feminine elements are excluded from both the Old Testament and New Testament doctrine of deity. The God of the Bible is a sexless God. When Scripture speaks of God as “he” the pronoun is primarily personal (generic) rather than masculine (specific); it emphasizes God’s personal nature—and, in turn, that of the Father, Son and Spirit as Trinitarian distinctions in contrast to impersonal entities... Biblical religion is quite uninterested in any discussion of God’s masculinity or femininity... Scripture does not depict God either as ontologically

masculine or feminine. (Henry 1982, 159–60)

However well-intentioned, attempts to read a kind of mystical gendering into God—whether stereotypically

masculine, feminine, or both—reflect not so much careful biblical theology as “the long

arm of Paganism” (Martin 11). For it is pagan worldviews, the Jewish commentator Nahum Sarna reminds us, that are “unable to conceive of any primal creative force other than in terms of sex... [In Paganism] the sex element existed before the cosmos came into being and all the gods themselves were creatures of sex. On the other hand, the Creator in Genesis is uniquely without any female counterpart, and the very association of sex with God is utterly alien to the religion of the Bible” (Sarna 76).

And if the God of creation does not privilege maleness or stereotypical masculinity, neither did the Lord of redemption. Sayers’s response to the cultural assumption that women were human-not-quite-human has become rightly famous:

Perhaps it is no wonder that women were first at the Cradle and last at the Cross. They had never known a man like this Man—there never has been such another. A prophet and teacher who never nagged at them, never flattered or coaxed or patronised; who never made arch jokes about them, never treated them either as “The women, God help us!” or “The ladies, God bless them!; who rebuked without querulousness and praised without condescension; who took their questions and arguments seriously; who never mapped out their sphere for them, never urged them to be feminine or jeered at them for being

female; who had no axe to grind or no uneasy male dignity to defend; who took them as he found them and was completely unself-conscious. There is not act, no sermon, no parable in the whole Gospel which borrows its pungency from female perversity; nobody could possibly guess from the words and deeds of Jesus that there was anything “funny” about women’s nature. (Sayers 1975, 46)

It is quite likely that Lewis’s changing views on gender owed something to the intellectual and Christian ties that he forged with Dorothy L. Sayers. And indeed, in 1955—two years before her death, Lewis confessed to Sayers that he had only “dimly realised that the old-fashioned way... of talking to all young women was v[ery] like an adult way of talking to young boys. It explains,” he wrote, “not only why some women grew up vapid, but also why others grew us (if we may coin the word) viricidal [i.e., wanting to kill men]” (Lewis 2007, 676; Lewis’s emphasis). The Lewis who in his younger years so adamantly had defended the doctrine of gender essentialism was beginning to acknowledge the extent to which gendered behavior is socially conditioned. In another letter that same year, he expressed a concern to Sayers that some of the first illustrations for the Narnia Chronicles were a bit too effeminate. “I don’t like either the ultra feminine or the ultra masculine,” he added. “I prefer people” (Lewis 2007, 639; Lewis’s emphasis).

Dorothy Sayers surely must have rejoiced to read this declaration. Many of Lewis’s later readers, including myself, wish that his shift on this issue had occurred earlier and found its way into his better-selling apologetic works and his novels for children and adults. But better late than never. And it would be better still if those who keep trying to turn C. S. Lewis into an icon for traditionalist views on gender essentialism and gender hierarchy would stop mining his earlier works for isolated proof-texts and instead read what he wrote at every stage of his life.

Mary Stewart Van Leeuwen is Professor of Psychology and Philosophy at Eastern University, St. Davids, Pennsylvania.

This essay originally was presented as the Tenth Annual Warren Rubel Lecture on Christianity and Higher Learning at Valparaiso University on 1 February 2007.

The Cresset

Bibliography

Evans, C. Stephen. Wisdom and Humanness in Psychology: Prospects for a Christian Approach. Grand Rapids: Baker, 1989.

Gray, John. Men Are From Mars, Women Are From Venus. New York: HarperCollins, 1992.

Hannay, Margaret. C. S. Lewis. New York: Frederick Ungar, 1981.

Henry, Carl F. H. God, Revelation, and Authority. Vol. V. Waco, Texas: Word, 1982.

Lewis, C. S. The Collected Letters of C. S. Lewis, Vol. III. Walter Hooper, ed. San Francisco:

HarperSanFrancisco, 2007.

_____. The Discarded Image: An Introduction to Medieval and Renaissance Literature. Cambridge: Cambridge University, 1964.

_____. The Collected Letters of C. S. Lewis, Vol. I: 1905–1931. Walter Hooper, ed. San Francisco:

HarperSanFrancisco, 2004a.

_____. The Collected Letters of C. S. Lewis, Vol. II: 1931–1949. Walter Hooper, ed. San Francisco:

HarperSanFrancisco, 2004b.

_____. “On Three Ways of Writing for Children,”[1952] Reprinted in Of Other Worlds: Essays and Stories, ed., Walter Hooper, 22–34. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1975.

_____. “Priestesses in the Church?” [1948]. Reprinted in God in the Dock: Essays on Theology and Ethics, ed. Walter Hooper, 234–39. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1970a.

_____. “The Humanitarian Theory of Punishment,”[1954]. Reprinted in God in the Dock: Essays on Theology and Ethics, ed. Walter Hooper, 287–300. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1970b.

_____. “Psychoanalysis and Literary Criticism,”[1942]. Reprinted in Selected Literary Essays, ed. Walter Hooper, 286–300. Cambridge: Cambridge University, 1969.

_____. [N. W. Clerk, pseudo.] A Grief Observed. London: Faber and Faber, 1961.

_____. The Four Loves. London: Geoffrey Bles, 1960.

_____. Till We Have Faces. London: Geoffrey Bles, 1956.

_____. Surprised by Joy: The Shape of My Early Life. London: Collins, 1955.

_____. Mere Christianity. London: Collins, 1952.

_____. That Hideous Strength. London: John Lane the Bodley Head, 1945.

_____. The Abolition of Man. Oxford: Oxford University, 1943.

_____. A Preface to Paradise Lost. Oxford: Oxford University, 1942.

The Cresset

_____. Perelandra. London: The Bodley Head, 1942.

Martin, Faith. “Mystical Masculinity: The New Question Facing Women,” Priscilla Papers, Vol. 12, No. 2 (Winter 1998), 6–12.

Reynolds, Barbara. Dorothy L. Sayers: Her Life and Soul. New York: St. Martins, 1993.

Sarna, Nahum M. Understanding Genesis: The Heritage of Biblical Israel. New York: Schocken, 1966.

Sayer, George. Jack: C. S. Lewis and His Times. San Francisco: Harper and Row, 1988.

Sayers, Dorothy L. “The Human-Not-Quite-Human,”[1946]. Reprinted in Dorothy L. Sayers, Are Women

Human?, 37–47. Downers Grove, Illinois: InterVarsity, 1975.

Sayers, Dorothy L. Gaudy Night. London: Victor Gollancz, 1935.

Sterk, Helen. “Gender and Relations and Narrative in a Reformed Church Setting.” In After Eden: Facing the Challenge of Gender Reconciliation, ed., Mary Stewart Van Leeuwen, 184–221. Grand Rapids:

Eerdmans, 1993.

Copyright © 2007 Valparaiso University Press www.valpo.edu/cresset

Merle — August 29, 2009

PSYCHOLOGY MATTERS

Psychology Matters Homepage

Glossary of Psychological Terms

RESEARCH TOPICS

Adolescents

Consumer/Money Issues

Decision Making

Driving Safety

Education

Environmentally Friendly Behaviors

Gender Issues

Health

Improving Human Performance

Law/Justice

Lifespan Issues

Memory

Parenting

Product Design

Psychological Well-Being

Safety

Sexuality

Sports/Exercise

Trauma, Grief & Resilience

Testing and Assessment

Violence/Violence Prevention

Workplace/Industry

Men and Women: No Big Difference

Studies show that one's sex has little or no bearing on personality, cognition and leadership

The Truth about Gender "Differences"

Mars-Venus sex differences appear to be as mythical as the Man in the Moon. A 2005 analysis of 46 meta-analyses that were conducted during the last two decades of the 20th century underscores that men and women are basically alike in terms of personality, cognitive ability and leadership. Psychologist Janet Shibley Hyde, PhD, of the University of Wisconsin in Madison, discovered that males and females from childhood to adulthood are more alike than different on most psychological variables, resulting in what she calls a gender similarities hypothesis. Using meta-analytical techniques that revolutionized the study of gender differences starting in the 1980s, she analyzed how prior research assessed the impact of gender on many psychological traits and abilities, including cognitive abilities, verbal and nonverbal communication, aggression, leadership, self-esteem, moral reasoning and motor behaviors.

Hyde observed that across the dozens of studies, consistent with the gender similarities hypothesis, gender differences had either no or a very small effect on most of the psychological variables examined. Only a few main differences appeared: Compared with women, men could throw farther, were more physically aggressive, masturbated more, and held more positive attitudes about sex in uncommitted relationships.

Furthermore, Hyde found that gender differences seem to depend on the context in which they were measured. In studies designed to eliminate gender norms, researchers demonstrated that gender roles and social context strongly determined a person's actions. For example, after participants in one experiment were told that they would not be identified as male or female, nor did they wear any identification, none conformed to stereotypes about their sex when given the chance to be aggressive. In fact, they did the opposite of what would be expected – women were more aggressive and men were more passive.

Finally, Hyde's 2005 report looked into the developmental course of possible gender differences – how any apparent gap may open or close over time. The analysis presented evidence that gender differences fluctuate with age, growing smaller or larger at different times in the life span. This fluctuation indicates again that any differences are not stable.

Learning Gender-Difference Myths

Media depictions of men and women as fundamentally “different” appear to perpetuate misconceptions – despite the lack of evidence. The resulting “urban legends” of gender difference can affect men and women at work and at home, as parents and as partners. As an example, workplace studies show that women who go against the caring, nurturing feminine stereotype may pay dearly for it when being hired or evaluated. And when it comes to personal relationships, best-selling books and popular magazines often claim that women and men don't get along because they communicate too differently. Hyde suggests instead that men and women stop talking prematurely because they have been led to believe that they can't change supposedly “innate” sex-based traits.

Hyde has observed that children also suffer the consequences of exaggerated claims of gender difference -- for example, the widespread belief that boys are better than girls in math. However, according to her meta-analysis, boys and girls perform equally well in math until high school, at which point boys do gain a small advantage. That may not reflect biology as much as social expectations, many psychologists believe. For example, the original Teen Talk Barbie ™, before she was pulled from the market after consumer protest, said, “Math class is tough.”

As a result of stereotyped thinking, mathematically talented elementary-school girls may be overlooked by parents who have lower expectations for a daughter's success in math. Hyde cites prior research showing that parents' expectations of their children's success in math relate strongly to the children's self-confidence and performance.

Moving Past Myth

Hyde and her colleagues hope that people use the consistent evidence that males and females are basically alike to alleviate misunderstanding and correct unequal treatment. Hyde is far from alone in her observation that the clear misrepresentation of sex differences, given the lack of evidence, harms men and women of all ages. In a September 2005 press release on her research issued by the American Psychological Association (APA), she said, “The claims [of gender difference] can hurt women's opportunities in the workplace, dissuade couples from trying to resolve conflict and communication problems and cause unnecessary obstacles that hurt children and adolescents' self-esteem.”

Psychologist Diane Halpern, PhD, a professor at Claremont College and past-president (2005) of the American Psychological Association, points out that even where there are patterns of cognitive differences between males and females, “differences are not deficiencies.” She continues, “Even when differences are found, we cannot conclude that they are immutable because the continuous interplay of biological and environmental influences can change the size and direction of the effects some time in the future.”

The differences that are supported by the evidence cause concern, she believes, because they are sometimes used to support prejudicial beliefs and discriminatory actions against girls and women. She suggests that anyone reading about gender differences consider whether the size of the differences are large enough to be meaningful, recognize that biological and environmental variables interact and influence one other, and remember that the conclusions that we accept today could change in the future.

Sources & Further Reading

Archer, J. (2004). Sex differences in aggression in real-world settings: A meta-analytic review. Review of General Psychology, 8, 291-322.

Barnett, R. & Rivers, C. (2004). Same difference: How gender myths are hurting our relationships, our children, and our jobs. New York: Basic Books.

Eaton, W. O., & Enns, L. R. (1986). Sex differences in human motor activity level. Psychological Bulletin, 100, 19-28.

Feingold, A. (1994). Gender differences in personality: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 116, 429-456.

Halpern, D. F. (2000). Sex Differences in Cognitive Abilities (3rd Edition). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum, Associates, Inc. Publishers.

Halpern, D. F. (2004). A cognitive-process taxonomy for sex differences in cognitive abilities. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 13 (4), 135-139.

Hyde, J. S., Fennema, E., & Lamon, S. (1990). Gender differences in mathematics performance: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 107, 139-155.

Hyde, J. S. (2005). The Gender Similarities Hypothesis. American Psychologist, Vol. 60, No. 6.

Leaper, C. & Smith, T. E. (2004). A meta-analytic review of gender variations in children's language use: Talkativeness, affiliative speech, and assertive speech. Developmental Psychology, 40, 993-1027.

Oliver, M. B. & Hyde, J. S. (1993). Gender differences in sexuality: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 114, 29-51.

Spencer, S. J., Steele, C. M. & Quinn, D. M. (1999). Stereotype threat and women's math performance. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 35, 4-28.

Voyer, D., Voyer, S., & Bryden, M. P., (1995). Magnitude of sex differences in spatial abilities: A meta-analysis and consideration of critical variables. Psychological Bulletin, 117, 250-270.

American Psychological Association, October 20, 2005

For more on GENDER ISSUES, click here.

Glossary of Psychological Terms

© 2009 American Psychological Association

Merle — August 29, 2009

Psychology Matters Homepage

Behaviors

Gender Issues

Think Again: Men and Women Share Cognitive Skills

Research debunks myths about cognitive difference

What the Research Shows

Are boys better at math? Are girls better at language? If fewer women than men work as scientists and engineers, is that aptitude or culture? Psychologists have gathered solid evidence that boys and girls or men and women differ in very few significant ways -- differences that would matter in school or at work -- in how, and how well, they think.

At the University of Wisconsin, Janet Shibley Hyde has compiled meta-analytical studies on this topic for more than 10 years. By using this approach, which aggregates research findings from many studies, Hyde has boiled down hundreds of inquiries into one simple conclusion: The sexes are more the same than they are different.

In a 2005 report, Hyde compiled meta-analyses on sex differences not only in cognition but also communication style, social or personality variables, motor behaviors and moral reasoning. In half the studies, sex differences were small; in another third they were almost non-existent. Thus, 78 percent of gender differences are small or close to zero. What's more, most of the analyses addressed differences that were presumed to be reliable, as in math or verbal ability.

At the end of 2005, Harvard University's Elizabeth Spelke reviewed 111 studies and papers and found that most suggest that men's and women's abilities for math and science have a genetic basis in cognitive systems that emerge in early childhood but give men and women on the whole equal aptitude for math and science. In fact, boy and girl infants were found to perform equally well as young as six months on tasks such as addition and subtraction (babies can do this, but not with pencil and paper!).

The evidence has piled up for years. In 1990, Hyde and her colleagues published a groundbreaking meta-analysis of 100 studies of math performance. Synthesizing data collected on more than three million participants between 1967 and 1987, researchers found no large, overall differences between boys and girls in math performance. Girls were slightly better at computation in elementary and middle school; in high school only, boys showed a slight edge in problem solving, perhaps because they took more science, which stresses problem solving. Boys and girls understood math concepts equally well and any gender differences narrowed over the years, belying the notion of a fixed or biological differentiating factor.

As for verbal ability, in 1988, Hyde and two colleagues reported that data from 165 studies revealed a female superiority so slight as to be meaningless, despite previous assertions that “girls are better verbally.” What's more, the authors found no evidence of substantial gender differences in any component of verbal processing. There were even no changes with age.

What the Research Means

The research shows not that males and females are – cognitively speaking -- separate but equal, but rather suggests that social and cultural factors influence perceived or actual performance differences. For example, in 1990, Hyde et al. concluded that there is little support for saying boys are better at math, instead revealing complex patterns in math performance that defy easy generalization. The researchers said that to explain why fewer women take college-level math courses and work in math-related occupations, “We must look to other factors, such as internalized belief systems about mathematics, external factors such as sex discrimination in education and in employment, and the mathematics curriculum at the precollege level.”

Where the sexes have differed on tests, researchers believe social context plays a role. Spelke believes that later-developing differences in career choices are due not to differing abilities but rather cultural factors, such as subtle but pervasive gender expectations that really kick in during high school and college.

In a 1999 study, Steven Spencer and colleagues reported that merely telling women that a math test usually shows gender differences hurt their performance. This phenomenon of “stereotype threat” occurs when people believe they will be evaluated based on societal stereotypes about their particular group. In the study, the researchers gave a math test to men and women after telling half the women that the test had shown gender differences, and telling the rest that it found none. Women who expected gender differences did significantly worse than men. Those who were told there was no gender disparity performed equally to men. What's more, the experiment was conducted with women who were top performers in math.

Because “stereotype threat” affected women even when the researchers said the test showed no gender differences – still flagging the possibility -- Spencer et al. believe that people may be sensitized even when a stereotype is mentioned in a benign context.

How We Use the Research

If males and females are truly understood to be very much the same, things might change in schools, colleges and universities, industry and the workplace in general. As Hyde and her colleagues noted in 1990, “Where gender differences do exist, they are in critical areas. Problem solving is critical for success in many mathematics-related fields, such as engineering and physics.” They believe that well before high school, children should be taught essential problem-solving skills in conjunction with computation. They also refer to boys having more access to problem-solving experiences outside math class. The researchers also point to the quantitative portion of the Scholastic Aptitude Test (SAT), which may tap problem-solving skills that favor boys; resulting scores are used in college admissions and scholarship decisions. Hyde is concerned about the costs of scientifically unsound gender stereotyping to individuals and to society as a whole.

Sources & Further Reading

Hyde, J. S., & Linn, M. C. (1988). Gender differences in verbal ability: A meta- analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 104, 53-69.

Hyde, J.S., Fennema, E., & Lamon, S. (1990). Gender differences in mathematics performance: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 107, 139-155.

Hyde, J.S. (2005) The gender similarities hypothesis. American Psychologist, 60(6), 581-592.

Spelke, Elizabeth S. (2005). Sex differences in intrinsic aptitude for mathematics and science?: A critical review. American Psychologist, 60(9), 950-958.

Spencer, S.J., Steele, C.M., & Quinn, D.M. (1999) Stereotype threat and women's math performance. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 35, 4-28.

American Psychological Association, January 18, 2006

Learn more about EDUCATION, TESTING AND ASSESSMENT or GENDER ISSUES

Glossary of Psychological Terms

© 2009 American Psychological Association

Merle — August 29, 2009

Below is an email I wrote to Oxford University Gender communication professor Deborah Cameron author of the great important book,The Myth Of Mars and Venus Do Men and women Really Speak Different Languages?.

Dear Deborah,

I recently read your great important book, The Myth Of Mars & Venus. You had said in your book that Deborah Tannen doesn't believe in natural gender differences in the mind, but I just read a bad review of the book, The Female Brain on Amazon.com US by psychologist David H.Perterzell.

I also thought you would want to know that John Gray got his "Ph.D" from Columbia Pacific University which was closed down in March 2001 by the California Attorney General's Office because he called it a diploma mill and a phony operation offering totally worthless degrees!

Also there is a Christian gender and psychology scholar and author psychology professor Dr. Mary Stewart Van Leewuen who teaches the psychology and Philosophy of Gender at the Christian College Eastern College here in Pa. She has several online presentations that were done at different colleges from 2005- the present debunking the Mars & Venus myth.

One is called , Opposite Sexes Or Neighboring Sexes and sometimes adds, Beyond The Mars/Venus Rhetoric in which she explains that all of the large amount of research evidence from the social and behavorial sciences shows that the sexes are very close neighbors and that there are only small average differences between them many of which have gotten even smaller over the last several decades which she says happened after 1973 when gender roles were less rigid and that genetic differences can't shrink like this and in such a short period of time, and that most large differences that are found are between individual people and that for almost every trait and behavior there is a large overlap between them and she said so it is naive at best and deceptive at worst to make claims about natural sex differences. etc.

She says he claims Men are From Mars & Women are From Venus with no emperical warrant and that his claim gets virtually no support from the large amount of psychological and behavioral sciences and that in keeping in line with the Christian Ethic and with what a bumper sticker she saw said and evidence from the behavioral and social sciences is , Men Are From,Earth ,Women Are From Earth Get Used To It. Comedian George Carlin said this too!

She also said that such dichotomous views of the sexes are apparently popular because people like simple answers to complex issues including relationships between men and women. She should have said especially relationships between them.

Sociologist Dr.Michael Kimmel writes and talks about this also including in his Media Education Foundation educational video. And he explains that all of the evidence from the psychological and behavioral sciences indicates that women and men are far more alike than different.

You also quoted Mark Liberman the language professor of University of Penn as recognizing this but on his language log he quotes biological determinists such as Michael Gurian, the author of The Female Brain and Leonard Sax Why Gender Matters and even though he criticizes and debunks some of what they say as false and pseudo science he says that some of their claims about innate brain differences are right and he says that what they say about how we should treat girls and boys and men and women differently at home, at school and in the workplace accordingly is probably true.

He also admits that there is a popular trend recently of using some pseudo science claims, exaggerating some real differences and claiming that it's all hard wiring and attributing the way the sexes, hear,see, think, feel, act etc to neurological differences. But he says now there are psychological, and neurological differences between the sexes sometimes big ones but some of this just seems to made up.

Yet Dr.Mary Stewart Van Leewuen says that there are no consistent large psychological sex differences found.

I have an excellent book from 1979 written by 2 parent child development psychologists Dr. Wendy Schemp Matthews and award winning psychologist from Columbia University, Dr.Jeane Brooks-Gunn, called He & She How Children Develop Their Sex Role Idenity.

They thoroughly demonstrate with tons of great studies and experiments by parent child psychologists that girl and boy babies are actually born more alike than different with very few differences but they are still perceived and treated systematically very different from the moment of birth on by parents and other adult care givers. They go up to the teen years.

I once spoke with Dr.Brooks-Gunn in 1994 and I asked her how she could explain all of these great studies that show that girl and boy babies are actually born more alike with few differences but are still perceived and treated so differently anyway, and she said that's due to socialization and she said there is no question, that socialization plays a very big part.

I know that many scientists know that the brain is plastic and can be shaped and changed by different life experiences and different enviornments too and Dr.Mary Stewart Van Leewuen told this to me too when I spoke to her 10 years ago.

Also there are 2 great online rebuttals of the Mars & Venus myth by Susan Hamson called, The Rebuttal From Uranus and Out Of The Cave: Exploring Gray's Anatomy by Kathleen Trigiani.

Also have you read the excellent book by social psychologist Dr.Gary Wood at The University of Birmingham called, Sex Lies & Stereotypes:Challenging Views Of Women, Men & Relationships? He clearly demonstrates with all of the research studies from psychology what Dr.Mary Stewart Van Leewuen does, and he debunks The Mars & Venus myth and shows that the sexes are biologically and psychologically more alike than different and how gender roles and differences are mostly socially created.

Anyway, if you could write back when you have a chance I would really appreciate it.

Thank You

Merle — August 29, 2009

This is Google's cache of http://ec.europa.eu/research/research-eu/women/article_women16_en.html.

Text-only version

Special issue – April 2009

Home

NEUROBIOLOGY

The brain, caught between science and ideology

Catherine Vidal, neurobiologist and Research Director at the Institut Pasteur (FR), does not limit her activities to her fundamental work, in particular on pain, memory and neurodegenerative ailments. This brain specialist also devotes her time to popularising science and to the relations between science and society.

Catherine Vidal – “As it develops, the brain integrates outside elements associated with its owner’s personal history.” © CNRS

©Shutterstock

Let’s start with a very direct question: is the brain sexed?

The scientific answer is, paradoxically, yes and no. Yes, because the brain controls the reproductive functions. Male and female brains are not identical, in every species, including our own, because sexual reproduction involves different hormone systems and sexual behaviours, which are controlled by the brain.

But the answer is also no, because when we look at the cognitive functions, it is cerebral diversity which reigns, independently of gender. For thought to emerge, the brain needs to be stimulated by its environment. At birth, just 10 % of our 100 billion neurons are inter-connected. The 90 % of remaining connections will be constructed progressively depending on the influence of the family, education, culture and society. In this way, during its development, the brain integrates external elements associated with its owner’s personal history. We call this cerebral plasticity; which is why we all have different brains. And the differences between individuals of one and the same gender are so great as to outweigh any differences between the genders.

In fact, behind your question is the fundamental problem of the degree to which behaviour is innate and to which it is acquired – an essential question that philosophers and scientists have been debating for centuries. This remains an ideologically-charged subject, which the media adore.

Absolutely. The media often echo works that argue that cerebral specialisation differs between male and female. They say, for example, that language functions are undertaken by both hemispheres only in women’s brains. What do you say?

The theories on the hemispheric differences between the sexes in language appeared over thirty years ago. They have not been confirmed by recent brain imaging studies which allow us to see the living brain at work. These theories are often based on observations carried out on very small samples – often a dozen people. People continue to quote these studies whereas contemporary scientific reality is very different. Meta-analyses, which draw conclusions from all the experiments published in scientific literature and cover several hundred men and women, show that there is no statistically significant difference between the sexes in the hemispheric distribution of language zones. This is explained by the fact that the location of these language zones differs considerably from one individual to the next, with this variability being more important than a possible variability between the sexes.

Another proposed idea is that the male brain is more suited to abstract reasoning, in particular mathematics.

These conceptions have no biological foundation. This is illustrated by two major studies that were published last year in Science. A first investigation took place in 1990 in the United States, involving a sample of 10 million pupils. Statistically speaking, boys did better than girls in maths tests. Certain people interpreted this as a sign of the inaptitude of the female brain in this field. The same study, commissioned in 2008 (1), this time shows girls scoring as well as boys. It’s hard to imagine that in less than two decades there has been a genetic mutation to increase their aptitude in maths! These results are due simply to the development of the teaching of science and the growing gender mix of scientific fields. Another study (2) carried out in 2008 on 300 000 adolescents, in 40 countries, has shown that the more the socio-cultural environment is favourable to male-female equality, the better the girls score in maths tests. In Norway and Sweden, the results are comparable. In Iceland the girls beat the boys, while the boys outperform the girls in Turkey and Korea.

One argument that is frequently advanced to explain unequal performances in maths is that men succeed better in three-dimensional geometric-type tasks. What is this idea based on?

Experimental psychology does indeed show that men often perform better on tests on the mental representation of three-dimensional objects. But one forgets to mention the influence of the context in which these performance differences take place. If, before carrying out this test in a classroom, pupils are told that this is a geometry exercise, the boys will generally get better results. But if the same group is told that this is a drawing test, the girls will perform as well as the boys. These experiments clearly show that self-esteem and the internalisation of gender stereotypes play a decisive role in the scores obtained in this type of test.

In the end, what are the challenges for research on the differences between men’s and women’s brains?

It is fascinating to look for the origins of these differences beyond the simple description of them. These origins are to be found in biology, but in particular in history, culture and society. One major advance of neurobiological research has been a revaluation of the extraordinary plastic capacity of the brain. It is not justifiable to invoke biological differences between the sexes to justify the different distribution between men and women in society.

But this ‘biologising’ vision continues to satisfy people as providing a sort of scientific justification for the existence of manifest inequalities. In this way people use the theory of evolution to explain that men find their bearings better in space because, in prehistoric times, they went hunting mammoths while the women remained in the cave looking after the children. This scenario is totally speculative – no one was there to see whether it really happened like that. Any prehistory specialists will tell you that no document – fossils, cave paintings, graves, or the like – reveals any details of the kind on the social organisation and division of labour among our ancestors.

How do you explain the renewed interest in these questions over the past 20 or so years?

First of all by the fact that these studies are easily taken up by the media – an aspect to which the publishers of scientific journals, including the most prestigious, are unfortunately sensitive. Second, by the development of cerebral imaging technologies which initially gave new life to the old theories on the inequality between men and women explained by the differences in their brains. But the more cerebral imagery progresses the more we observe, as I said, the major role of the plasticity of the brain and the variability of its functioning from one individual to another, independent of gender.

I find it regrettable that studies of doubtful scientific value continue to be so widely echoed. But other things are there to make me optimistic. The fact that the 2008 Nobel Prize in physiology and medicine rewarding the discovery of the AIDS virus was awarded jointly to Luc Montagnier and his main female collaborator, Françoise Barré-Sionoussi shows that mentalities are changing. Formerly only the head of the laboratory was rewarded… Think back here to Rosalind Franklin, the British biophysicist who played a key role in elucidating the double-helix structure of DNA and whose work was taken over by James Watson and Francis Crick, the winners of the Nobel Prize in physiology and medicine in 1962. We are seeing a real awareness of women’s role in research. But this evolution is slow. And belief in change is, alas, stronger than change itself…

Interview by Mikhaïl Stein

C.Guiso et al., Culture, Gender and Math, Science (2008), 320: 1164-1165.

J.S. Hude et al., Gender Similarities Characterize Math Performance, Science (2008), 321 : 494-495.

TOP

Find out more

Selected publications by Catherine Vidal

Sexe et pouvoir, with Dorothée Benoit-Browaeys, Paris, Belin, 2005. Translated into Italian, Japanese and Portuguese.

Féminin/Masculin: mythes et idéologie, Paris, Belin, 2006.

Hommes, femmes: avons-nous le même cerveau?, Paris, Le Pommier, 2007.

Cerveau, sexe et liberté, DVD Gallimard/ CNRS, col. «La recherche nous est contée», Paris, 2007.

Sociological Images Update (Sept. 2009) » Sociological Images — October 2, 2009

[...] As we often do, we have more examples of gendered kids’ products: boys’ and girls’ versions of a book on “how to be the best at everything.” They make a nice pair with the girls’ and boys’ doodle books we posted here. [...]

Danny — April 4, 2010

Something that could be interesting:

My step-dad has three young daughters from a previous marriage. One day he took them to the bookstore where they saw the "How to be the Best at Everything" books. The boys and the girls ones. One girl went directly for the "Girls" book while the other (her mirror twin, if that means anything) went for the "Boys" book. He bought them both.

We also found out later that a lot of the content was similar, and a lot of the "Girls" book centered around typically "boy" activities like tying knots(at least if I remember correctly).

Perhaps an interesting view on one dad fighting against societal norms. Not that he even realized that was what he was doing.