American workers have lost power relative to their employers since the heyday of unionization during the industrial era. One way in which employees gained was through the extension of benefits to full-time workers: salary, relative job security, health insurance, sick pay, paid vacation, parental leave, etc. Full-time jobs, however, are being replaced by part-time jobs, and with them have gone much of the power and most of the benefits that workers were able to gain through unionization.

You would think, though, that jobs that require a high level of education and training might be immune from these trends. Perhaps not.

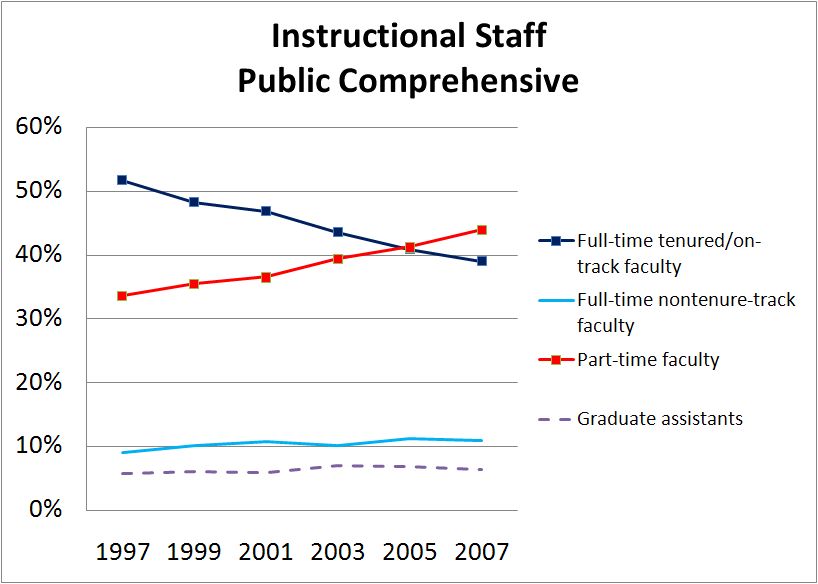

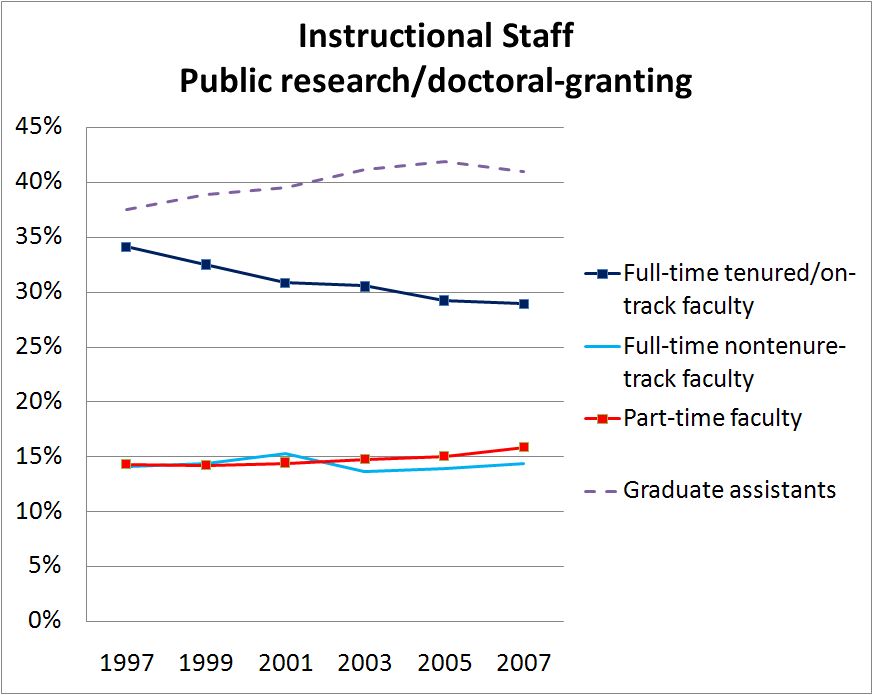

The American Federation of Teachers released a report that included data on the percentage of employees at U.S. colleges and universities that are full-time tenure-track professors, full-time non-tenure track, adjunct (part-time) professors, and graduate students. As you can see, the percentage of full-time tenure-track professors is decreasing and we are being replaced by other types of employees who cost the institution much less (graphs borrowed from MontClair SocioBlog).

This is a problem from a labor perspective in that it strips power away from employees, putting it squarely back into the hands of employers. It may also be a problem in terms of the quality of education. Adjunct professors are often terrific, but anyone who is overworked and underpaid is likely to invest less in their product. I wonder, too, if this impacts the rate of scientific research (fewer full-time tenure- track professors= less research). Any other thoughts on this trend?

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

Comments 19

Anna! — May 23, 2009

most of the part-time and full-time but non-tenure-track professors that i've had really deserve to put up a step higher... they have huge commutes to teach at school all over california, or have been at my school for decades without the benefits of tenure. it's pretty unfair to them, i think. i don't find a huge difference in my education, except that part time faculty have almost no office hours and it makes it harder to get extra help from them.

Vettekaas — May 23, 2009

This doesn't make me feel hopeful for job prospects after grad school x-(

L — May 23, 2009

It may also be a problem in terms of the quality of education. Adjunct professors are often terrific, but anyone who is overworked and underpaid is likely to invest less in their product.

Yes, certainly. I've adjuncted and been a graduate teaching assistant (GTA), and, honestly, I was treated better as a GTA than as an adjunct instructor -- I had an office, a two-year (rather than semester-long) contract, and plenty of departmental support for instruction.

There are tons and tons of problems with the shift toward increased reliance upon adjunct faculty in all aspects of higher education. For one thing, there is typically little to no office space for adjunct faculty, putting student-teacher confidentiality at risk as faculty share offices and putting educational quality at risk for lack of space for conferences, etc. For another thing, many adjunct faculty are hired mere weeks before the start of a semester, making their preparation for the semester more difficult and likely more superficial and unstable and putting students' quality education at risk.

And those are just the issues affecting educational quality; they don't even touch on material issues affecting adjunct faculty themselves. Many, many adjuncts have no access to institutionally supported health benefits -- I have had to purchase my own medical insurance since I began adjuncting because they just don't cover it. Add to that the fact that adjuncts are paid much, much less than their similarly qualified full-time counterparts, and you have a class of people being exploited, essentially.

Some colleges and universities are working diligently to correct these discrepancies -- by offering health insurance after so many sections, by paying more per hour/class, by scrounging up space for offices on campus, by providing more curricular support for new-to-the-institution instructors -- but much more needs to be done before being a part-time instructor in higher education actually pays a living wage. And before anyone jumps on me with "yeah but you're part-time, so you shouldn't expect the benefits of full-time!": as the chart in the OP makes clear, colleges and universities are simply eliminating full-time positions because relying on "part-time" instructors costs less (the majority of these "part-timers" teach more sections than full-time instructors each semester -- but they often spread their teaching out across two or more institutions in order to do so if possible). As this process continues, there are fewer and fewer full-time opportunities available, so adjuncts just can't find full-time teaching work (and then the market is flooded with teachers seeking part-time work, making it an employer's market -- not good for decent wages for already relatively low-paying work).

Universities and colleges, if they expect to continue providing their students with solid educations, must stop cutting budget corners by paying highly qualified adjuncts wages that force adjuncts into teaching more than they should at various institutions just to scrape by.

The FORUM is a newsletter dedicated to adjunct (composition) instruction issues -- check it out for more information about what folks in the field are doing about the Part-Time Problem.

Vidya — May 23, 2009

My advice to anyone considering doing a PhD has become, 'If you can't get into your top one or two university choices, don't even bother.' It sounds harsh, but even graduates from the 'top' programs in their fields are finding it impossible to get a TT position, and there is a huge, huge glut of graduates out there. I really wish there was some way to scale back admissions to PhD programs in general -- only the very best candidates, only in limited numbers.

That being said, the system has to change radically, and I don't see that happening unless the government steps in (I'm thinking about the Canadian context here, btw) and legislates that universities must maintain a certain percentage of TT faculty to retain their degree-granting status.

Pat — May 24, 2009

TT jobs are probably on their way out, complete. Anyone expecting to get such a job is fooling themselves (says a social scientist PhD student at the #2 institution for his field). The system will not change radically, and while those of us in the system may think it's not a good change, we are far far far far far in the minority on this opinion. When the typical citizen thinks of tenure they think of aloof professors wasting their time on research with no applicability to the rest of society.

Expect humanities and social science TT jobs to be the first to go. The generation of PhD students coming out now will be one of the last with relatively large-scale TT employment.

And guess what? The world won't end.

NL — May 24, 2009

I'm an adjunct, and I make about minimum wage. It's pretty awesome trying to live and pay back loans on that. I definitely had it better as a TA -- like L, I had benefits, an office (shared with 6 other people), and a 2-year contract.

The grad chair of my former department just got tenure. I'm very happy for him; he worked very hard. But I don't think I'll be seeing too many more happy notes like that as the years go by.

Ellen — May 24, 2009

Wow Vidya, that is some incredibly bad and elitist advice. First, graduate education is not just about getting a job. Second, there are plenty of great jobs outside academia (for many, but not all disciplines). And occasionally, an interesting and less studied topic of expertise can help you get a job. There are plenty of ways to market yourself besides with the name of the school that you went to. It is true that top tier schools tend to be elitist and only hire graduates from top tier schools. But those are not the only jobs to be had.

Vidya — May 24, 2009

I should clarify that I don't believe that 'top university' =/= 'top program' (in Canada, I find the discrepancy shockingly large, in fact).

And, yes, there are some fields/disciplines in which a PhD can assist in getting a job outside academia -- but mine is not one of these; almost everyone I know who is doing a doctorate aspires to find a TT position, and most will not be able to do so.

Also, yes, I believe doctoral study *should* be elitist -- not in the sense of social class or economic standing (few students at my own institution possess much of these), but meritocratically. (Incidentally, I know several professors hired for TT positions in recent years, and all were the recipients of major government-funded scholarships during their PhD studies. I haven't seen much in the way of academia-career possibilities materialize for non-scholarship-winning graduates.)

Penny — May 24, 2009

I did doctoral study with absolutely no interest in a tenure-track position. I did it because I had an interesting research project I would have done with or without a degree at the end; and because I was offered a very nice three-year fellowship, and because it meant spending time in a small program with good people. Because I did the program with no TT intentions, I was able to make it a good experience for me. But...if I spent the whole time worrying about academic job prospects, tailoring my work to that goal, and still landed off campus, I could definitely see that being a bitter disappointment.

Ellen — May 24, 2009

I am guessing you aren't studying sociology if you think anything is meritocratic.

Larry — May 25, 2009

"When the typical citizen thinks of tenure they think of aloof professors wasting their time on research with no applicability to the rest of society."

Pat -- do you have any evidence for this? Your post may be correct, but it reads like the standard evasion of activism.

PhDork — May 25, 2009

My handle might tell you that this issue hits close to home. Even before the economy tanked (and took almost all the jobs in my field with it), the move

If you read the Chronicle of Higher Ed, or the Education series they've been running in the NYT, or ed blogs, you'll know this has been coming for years, as universities are run as businesses, for profit, as the expense of its laborers. Tuition (which is *wildly* misnamed) goes toward buying and developing real estate, more dorm amenities; TT faculty are being replaced with squadrons of adjuncts who go without security, benefits, or even a decent wage, and more and more "administrators" are brought on, at higher salaries than the profs.

I love my field, but I hate the system, and if I had it to do all over again, I don't think I'd do grad school or A&S: I'd sell out (business, finance, etc.) and become a paper pusher who leaves her work at work. There is no meritocracy, and there's little future for people with PhDs in most humanities fields. I'm one of the most educated fools you'll ever meet.

PhDork — May 25, 2009

The first para got partially deleted, and should finish "...to a para-professional professoriate was well underway."

Becca — May 25, 2009

Vidya, I'm not so sure about your advice.

I know that in astronomy (my own field), the PhD institution does not make any statistical difference in the ability to get an astronomy job in academia later on. Here's the paper: http://arxiv.org/pdf/astro-ph/9904229

This is of course field specific, but astronomy is one field that definitely has a lack of permanent faculty positions available relative to the number of PhDs being produced. I'm betting it carries over into other fields. Anyone else read any studies about this? (The anecdotes always makes things seem way worse than they truly are, I've found.)

Rachel Jenkins — May 25, 2009

The way universities have recently been operating with increasing losses, many if not most, classes will soon be online to save money for both school and students.

I was just hired as an online teacher, and those classes have to be paid in advance, so don't lose money.

Jesse — May 26, 2009

This one is about the research question in the originating article. Actually, the demands on TT teaching (to absorb more students, more classes), make these positions *not* optimum for high quality research. Soft money researchers have, in principle, more time and attention to devote to research, as this is their mainstay, and what they are actually paid to do. On the down side, soft money researchers have to include their own salary in proposals, which make them less attractive to fund. All in all, university "biz" is following the globalization story, doing more of everything with fewer of everyone. Regarding teaching, an admin colleague recently observed the huge savings involved if a course could be delivered on a cell phone (through distance ed technology). Depressing. Coming soon from an ether-campus in an undisclosed location: the Tweet Degree.

For your reading pleasure « Living in interesting times — June 1, 2009

[...] “Employment Trends And Academic Labor,” Lisa Wade, Sociological Images: Seeing is Believing (May 23/09) [Thanks to Jonathan for the link.] [...]

Recruiter Bill — November 2, 2009

I have worked in staffing for over 20 years, in the last few I have had a lot of people looking to transition into industry as they have not been able to realize their career goals in academic settings.

The Best Jobs in America » Sociological Images — March 12, 2010

[...] race, race and the economic downturn, changes in type of work over time, gender and the wage gap, trends in academic employment, science/engineering Ph.D.s for women and minorities, changes in compensation by job sector, more [...]