Flashback Friday.

When I was in grad school studying sociology of agriculture, one thing we talked about was organic agriculture and the difference between “organic” and “sustainable.” Most consumers think of these words interchangeably. So, when many people think of an organic dairy farm they imagine something along the lines of these images, the top results for an image search of “organic dairy farm”:

So happy! So content! And, we assume, raised on a small family farm in a way that is humane and environmentally responsible. Those, are, after all, two of the things we expect when something is defined as “sustainable”: it is environmentally benign and humane. We also usually assume that workers would be treated decently as well.

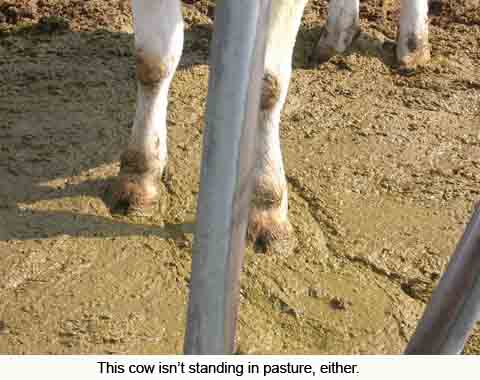

But there is no reason that those elements considered essential to sustainability have to have much to do with organic agriculture. Depending on who is doing the defining, being “organic” can involve very little difference from conventional agriculture. Having an organic dairy mostly just requires that the cows not have antibiotics or homones used on them, eat organic feed, and have access to grass a certain number of days per year. In and of itself, organic certifications don’t guarantee long-term environmental sustainability or overall humane treatment of livestock.

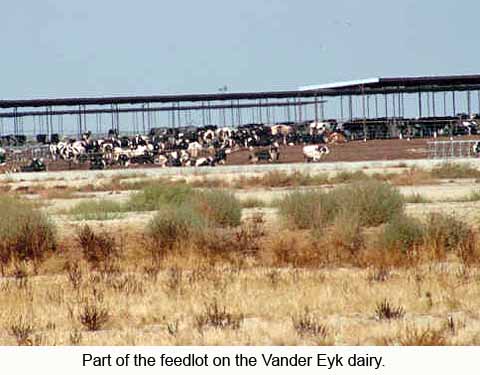

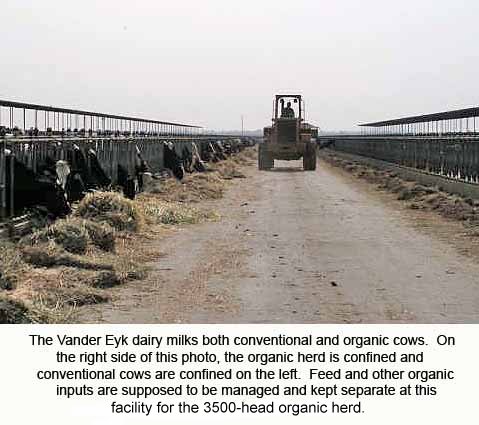

A great illustration of how little the modes of production on organic farms may differ from conventional agriculture is the Vander Eyk dairy. It is an operation in California with over 10,000 dairy cows. Here are some images (found here and here):

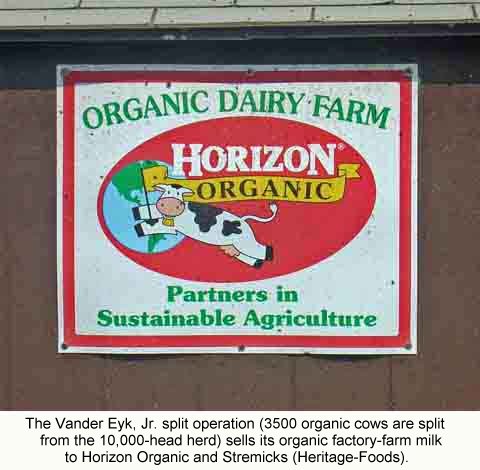

As the caption to the last image makes clear, the Vander Eyk dairy had two herds on the same property, but segregated from one another: the majority of the herd produced conventional milk, while 3,500 cows produced organic milk for sale under the Horizon brand:

In 2007 the Vander Eyk dairy lost its organic certification for violating the requirement that organic dairy cows spend a certain amount of time on pasture. They had cows on pasture, but they were non-milking heifers, not cows that were being milked at the time. What we see here is that the label “organic” doesn’t guarantee most of the things we associate with the idea of organic or sustainable agriculture (and in cases like Vander Eyk, may not even guarantee the things the label is supposed to cover).

This isn’t just in the dairy industry. As Julie Guthman explains in her book Agrarian Dreams: The Paradox of Organic Farming in California, many types of organic agriculture include things you might not expect. For instance, organic producers in California joined with other producers to oppose making the short-handled hoe illegal — the bane of agricultural workers everywhere (and most infamously associated with sharecropping in the South in the early 20th century) — because they want workers to do lots of close weeding to make up for not spraying crops with pesticides. So, though we often assume organic farmers would be labor-friendly, in that case they opposed a change that agricultural workers supported.

Many organic crops are grown on farms that are the equivalent of the Vander Eyk dairy; most of the land is in conventional production, but a certain number of acres are used to grow organic versions of the same thing. Often the producer, which may be an individual farmer or a corporation such as Dole, isn’t very committed to organics; if a pest infestation threatens to ruin a crop, they’ll just spray it and then sell it on the conventional market rather than lose it. They may then have to have the land re-certified as “in transition,” meaning it hasn’t been pesticide-free long enough to be declared completely organic, but many consumers don’t pay too much attention to such distinctions.

The Vander Eyk dairy — and lots more examples of large containment-facility operations selling to Horizon and other brands at the Cornucopia Institute’s photo gallery — are interesting examples of how terms like “organic,” “green,” and “eco-friendly” don’t necessarily mean that the item is produced according to any of the standards we often assume they imply.

Originally posted in 2009.

Gwen Sharp is an associate professor of sociology at Nevada State College. You can follow her on Twitter at @gwensharpnv.

Comments 23

emfole — March 10, 2009

thank you! im sending this to all the people who are like "don't worry this is from happy ORGANIC cows" Fact is that when animals are used for human benefit, the animals will NEVER be treated well.

Katie in Berkeley — March 10, 2009

My impression is that Horizon is particularly bad about this sort of thing. In general, non-national brands of organic dairy are probably a better bet.

Amy — March 10, 2009

If you're interested in this kind of thing, it goes without saying Michael Pollan's The Omnivore's Dilemma is a must-read. He explains this issue in depth, yet eloquently enough to follow. I was riveted. And I started being MUCH more careful about the dairy (and meats and vegetables) I eat.

Sarahjane — March 10, 2009

This reminded me of all the "Happy Cows come from California" comercials that I see so frequently.

http://www.realcaliforniamilk.com/happycowstv/tvcommercials

Umlud — March 10, 2009

My original thought was, "Well, duh." Organic doesn't mean humane. It doesn't mean green. It only means what its requirements make it do. The extrapolation of "organic" to "green" is something that people want to do, and no one in the industry is willing to rip that veil from people's eyes.

Reagan — March 10, 2009

This article is a pretty awesome examination of the factory farm model: http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9C06E5DB153BF932A05750C0A9649C8B63&sec=health&spon=&pagewanted=print

Captain Crab — March 11, 2009

To read about the Organic Farmer of the Year

Go here:

http://captaincrabtales.blogspot.com/2009/03/tom-and-irene-frantzen-organic-farmers.html

and here:

http://www.mosesorganic.org/attachments/broadcaster/foy09.html

Sociological Images — March 11, 2009

[...] Sociological Images. A branch of the journal Contexts from the American Sociological Association. What does "organic" look like? What happens after the oil boom dries up in a town? There are many discussions about the way bodies [...]

Lauralee — March 11, 2009

@Katie in Berkeley " . . . non-national brands of organic dairy are probably a better bet."

For several reasons, among them: organic milk sold nationally is almost always "ultra-pasteurized." This method of pasteurization cooks the milk at high temperatures (over 200 deg. F) which wreaks havoc on milk proteins. As a result, ultra-pasteurized milk often tastes "cooked" and can be problematic when used for food prep (e.g. puddings and sauces), in addition to affecting digestibility and nutritional content.

Anonymous — March 11, 2009

Gwen, you know anything about cow treatment for the cows producing milk that goes into the Organic Valley co-op milk?

Gwen — March 11, 2009

I don't know anything for certain about Organic Valley. However, when I was in Wisconsin, the general feeling among the people I knew who studied the dairy industry was that it was better overall than Horizon. Most Organic Valley producers come from Wisconsin and Minnesota, and if nothing else they tend to have smaller family-owned producers (which doesn't guarantee decent treatment of cattle, clearly, but makes it more likely they'll spend at least some time on pasture than if it's a 10,000-cow dairy).

Several times I drove by farms that were identified as Organic Valley producers, and they didn't, from the road, LOOK like huge confinement-only places.

For what it's worth, I always chose Organic Valley whenever I could. I very rarely have access to it here in Vegas, since Organic Valley doesn't ship as widely as Horizon does. I won't buy Horizon products--I feel like their "organic" label is just marketing and isn't worth the extra money. I feel comfortable with Organic Valley, just from the information I've been able to gather here and there. I'm sure there are problems with it, as there are with any company, but I think it comes a lot closer to encompassing some of the things we think of when we think of "organic" than other companies do.

Sorry I can't be more helpful than that.

easyVegan.info » Blog Archive » easyVegan Link Sanctuary, 2009-03-12 — March 12, 2009

[...] Sociological Images: WHAT DOES “ORGANIC” LOOK LIKE? [...]

anon — March 12, 2009

It's fine to point out the limits of organic, but this kind of thing is often written as if organic is bad, or just the same as conventional. But organic means far less pollution, no harmful chemicals, and requirements of some grazing, so yes, organic does mean that the product is likely to be greener and more humane. The conclusion that some people have come to -- local or family farm is more important than organic -- is foolish, because there are lots of family farmers who use way too much pesticides, without taking measures to avoid polluting their neighbors' wells and rivers. Pace Pollan, having conversations with farmers is nice, but I don't think it's a good way to find out whether their practices are humane or sustainable or not. We should be encouraging small farmers to get certified, not encouraging people to turn away from organic to conventional small farmers.

Of course we should tighten organic standards, but we should also outlaw (or impose much more restrictive regulations) on the kind of massive factory farm that this article criticizes. It would raise the price of all milk and meat, but people have been able to afford milk and meat for 1000's of years without concentrating them in such inhumane and unsustainable ways.

hypatia — March 13, 2009

"I don’t know anything for certain about Organic Valley. However, when I was in Wisconsin, the general feeling among the people I knew who studied the dairy industry was that it was better overall than Horizon. Most Organic Valley producers come from Wisconsin and Minnesota, and if nothing else they tend to have smaller family-owned producers (which doesn’t guarantee decent treatment of cattle, clearly, but makes it more likely they’ll spend at least some time on pasture than if it’s a 10,000-cow dairy)."

I'm definitely starting to think that the unhappiest cows come from California. I've been on Dairy farms in Minnesota, Wisconsin, Michigan, New York and Ontario (I have a friend who is a dairy manager) and none of them have had their bovines in conditions even close to as shown here. Yet both examples from California that I have seen have been similarly disgusting.

Right to Bleed » Sunday Speed — April 26, 2009

[...] organic is your [...]

I love Wegmans, I really do, but… — July 13, 2009

[...] as much as cars?” (TL,DR: yes) That’s good environmental stewardship! [edit: What Does Oraganic Look Like? from a sociology [...]

What Does an Organic Label Mean? » Sociological Images — March 6, 2010

[...] an eco-labeling website, ownership of organic brands, and what does “organic” look like? var addthis_language = 'en'; Leave a Comment Tags: discourse/language, [...]

Issa’s Reviews: Raising Baby Green Part One | LoveLiveGrow — November 22, 2010

[...] Are organic crops grown with care, or are they just grown “organically” until something goes wrong, at which point they’re sprayed down anyway and then sold as conventional crops? Is that what you want from the word organic? [...]

What Does Organic Food Mean Look « Recipes for Health — September 5, 2014

[…] What Does “Organic” Look Like » Sociological Images – What Does “Organic” Look Like. by Gwen Sharp, PhD, Mar 10, … don’t necessarily mean that the item is produced according to any of the standards we often … animals, discourse/language, environment/nature, food/agriculture. Spoofing Sex Symbolism: For Boys Only. Marketing with … […]

Bill R — October 3, 2014

Three things come to mind when I see the word organic on a product at the market: high price, marketing hype and bull shit.

safety — October 7, 2014

I hate to say it but the problem for the US started with market hunting of Bison; native cattle perfectly adapted to their conditions. They never needed to be driven hundreds of miles to escape the weather, or to be put indoors, never needed antibiotics for the different diseases in variable climates, ate wild pasture and put on weight prodigiously, made far more nutritious milk, leaner meat and better hide products. If we could change two things about the founding of America (and I'm admonishing British colonialism here as much as anything) it would be the treatment of indigenous people and the sustainable management of American native abundance that was the envy of the world. Both had much to teach us; both were sacrificed by pioneers in favour of European breeds and techniques that were not superior. From that point on, US agriculture had an artificiality about it that persists to this day. It propagated unsustainable practices to overcome its own deficiencies - cattle drives, range wars, monocropping like the corn belt, grain belt, rice belt and soy belt, subsidies, and worst, the use of slaves. Organic or sustainable - these terms need to be reclaimed to mean what they say, without compromise, or we need some new terms that serious farmers can claim without fear of even accidental hypocrisy

Veg Nik — October 7, 2014

Organic is better in terms of less use of chemicals, hormones, antibiotics, etc. in society and often better for personal and public health, which are benefits not to be underestimated, but has no effect on issues of cruelty or environmental sustainability.

It is better to not eat meat and dairy than to eat organic, though they of course are not mutually exclusive.

Eco-Eating

www.brook.com/veg