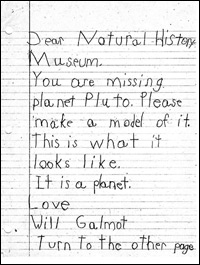

In case you missed it, a few years back there was a major brouhaha (limited mostly to the U.S.) because some astronomers began to argue that Pluto should be reclassified as a dwarf planet, part of the Kuiper belt. This started when, in 2001, the American Museum of Natural History (in New York) created a display about the solar system that did not include Pluto. At first the museum received letters (often from children) pointed out that Pluto was missing, such as this one (from an NPR story on the subject):

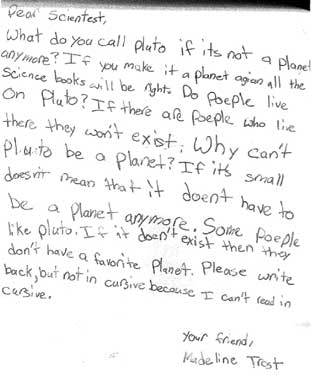

But then word got out that the museum left Pluto out of the display on purpose, and that the director of the museum argued that Pluto is not a planet. Then a real letter-writing campaign began, from both kids and adults (found here):

Text [some errors corrected for ease of reading]:

Dear Scientist,

What do you call Pluto if it’s not a planet anymore? If you make it a planet again all the science books will be right. Do people live on Pluto? If there are people who live there they won’t exist. Why can’t Pluto be a planet? If it’s small doesn’t mean that it doesn’t have to be a planet anymore. Some people like Pluto. If it doesn’t exist then they don’t have a favorite planet. Please write back, but not in cursive because I can’t read in cursive.

A Save Pluto movement had begun, including pro-Pluto websites, t-shirts, bumperstickers, and so on (at CafePress):

Some of these were clearly meant in a joking manner, but many of the letters sent to the museum or published in newspapers expressed realy anger over the change. Headlines announced that Pluto was being “demoted” from planet status. Amid lots of angry debate even among themselves, astronomers eventually voted to recategorized Pluto as a dwarf planet.

You might use these to talk about public controversies about scientific research. This is a particularly odd example because the public concern didn’t spring from arguments that the research was immoral or dangerous (claims used to oppose, say, embryonic stem cell research or cloning). The outrage about Pluto’s change in status mostly occurred in the U.S. and was based on the fact that people just seem to really like Pluto and consider it their “favorite” planet. Neil DeGrasse Tyson, director of the museum, suggests that this might be because of Disney’s cartoon dog Pluto. Regardless, a significant number of people wrote angry and even threatening letters to various outlets about a scientific reclassification that didn’t affect them in any real way; they just didn’t like it.

It’s also interested that Pluto’s reclassification was interpreted as a “demotion,” as though being a dwarf planet is clearly inferior to being a “real” planet, as though the objects in the solar system are arranged in a hierarchy based on size, and being anything other than a planet is a sad, sad fate. DeGrasse Tyson stresses that to astronomers, a dwarf planet isn’t “inferior to” a “regular” one–it’s just another category of things that exist in the galaxy. It’s an interesting example of how scientists’ perceptions of what their research means and the public’s interpretations may differ wildly.

NOTE: Mordecai comments,

First I want to say: All scientific classification is arbitrary. There is no such thing as a planet, or a mammal. These are terms humans put on them to try to make sense of the universe, not some built in truth.

Absolutely. I didn’t mean to imply the scientists were applying some ultimate truth about the universe when they re-classified Pluto. What I find interesting is what the controversy was based on: not “we think the data is wrong,” or “this is immoral or harmful,” but “Leave Pluto alone! It’s our favorite!” And the fact that it was really only a scandal in the U.S. is striking as well–whether it’s the character of Pluto or not, for some reason Americans are pretty much uniquely concerned about Pluto’s status.

Comments 18

mordicai — February 7, 2009

First I want to say: All scientific classification is arbitrary. There is no such thing as a planet, or a mammal. These are terms humans put on them to try to make sense of the universe, not some built in truth.

That being said, attempts to refine those systems to be more accurate are admirable. & The idea that the culture of science is open to sentimentality is appalling. I wonder how much of it stems from the fact that there is already a long standing argument between science & arbitrary belief-- heliocentric versus geocentric, natural selection versus intelligent design, meteorology versus Zeus...okay, kidding on that last one.

Becky — February 7, 2009

The uproar over Pluto really bothered me, because I thought it was a symptom of poor science education in this country. As scientists, we're not making it clear that science is a system of inquiry, not a collection of facts.

Laurel Kornfeld — February 7, 2009

The movement to reinstate Pluto is alive and well because the demotion was wrong in the first place. It's fine to classify a small planet that is not gravitaitionally dominant as a dwarf planet, but it makes no sense to say that a dwarf planet is not a planet at all, as four percent of the IAU did two years ago. Much of the uproar was over this linguistic nonsense and over the highly flawed process the IAU used to make this decision.

Opposition to Pluto's demotion is not limited to the US. It is true that many planetary scientists are American, and it is planetary scientists who are most opposed to this "reclassification" because it categorizes objects solely by where they are while ignoring what they are. If Earth were in Pluto's orbit, it would not be considered a planet according to the IAU definition because it would not be massive enough to clear that orbit of other Kuiper Belt Objects.

A definition that categories the same object as a planet in one location and not a planet in another location is fundamentally flawed. This issue, not the Disney dog, is the reason so many people found this "reclassification" offensive. Most people who care about this at all, whether children or adults, are people who already have some interest in astronomy and the solar system.

If the term dwarf planet is amended to be a subclass of planet, thereby brought in line with the use of the term "dwarf" in astronomy (dwarf stars are still stars; dwarf galaxies are still galaxies), much of this controversy would be resolved.

Gwen Sharp, PhD — February 7, 2009

I don't think the people helping their kids send in letters about Pluto were generally doing so out of any strong astronomy-based position on whether dwarf planets are or aren't a subset of planets. Their concern was based on something else entirely. Which is fine--as a sociologist, I find that fascinating.

billy joe — February 7, 2009

Pluto was the only 'planet' discovered by an american. pride is a factor. there was a much larger movement against the new classification amongst american astronomers than the global population.

We needed a classification for an object that was large enough to be round and planet like that hadn't cleared it's neighborhood of other similar objects, thus, the term 'dwarf planet' is applied.

Conrad Johnston — February 7, 2009

My BSc suggests I'm trained as a scientist, and I agree with Becky's statement "As scientists, we’re not making it clear that science is a system of inquiry, not a collection of facts."

However, Pluto's reclassification, although systematically correct, seems to me to lack Poetry.

I'd argue for keeping Pluto in the wrong category and teaching the reasons why. In the same way that the English language has weird little historic inconsistencies.

chuk — February 7, 2009

I think Becky's comment--"science is a system of inquiry, not a collection of facts"--is bang on! I've found it to be a very challenging idea to communicate to people though.

anna — February 7, 2009

my first instinct was that the planet list is something we learn at an early age and take as fact all throughout school/our lives. people's conceptions were disrupted. and perhaps it becomes particularly emotional because we grasp dearly to the limited "understanding" we have of space....

Dr. Robert Runte — February 7, 2009

Pluto also became a verb for a while -- as in an employee who was "downsized" would say to his friends, "I've been plutoed!"

cordelia9889 — February 8, 2009

There are a seemingly endless number of facebook groups 'defending' pluto--"When I Was Your Age, Pluto Was a Planet", etc. I don't know how relevant that is, but I feel like among college students who spend way too much time online (i.e. 90% of the people I know), facebook groups are a pretty good indicator of what people are thinking about en masse.

Elena — February 8, 2009

It's not as if the number of planets in the solar system was ever a fixed number. We knew only the inner planets up to Saturn until Uranus was discovered in 1781 and Neptune in 1846. Pluto was discovered as recently as 1930. That's within living memory.

As we've discovered a lot of dwarf planets since then, and at least one of them, Eris, is bigger than Pluto (which is smaller than some moons of the gas giants), there had to be a choice of where to draw the line -- either we got a solar system of twenty-whatever planets, or eight planets and an expandable list of outliers.

Becky — February 8, 2009

LK, there are many icy objects like Pluto in the Kuiper Belt, and as Elena points out, at least one is larger than Pluto. Classifying Pluto as a "dwarf planet" or a Kuiper Belt Object is a useful way to classify it with similar objects in terms of orbit, structure, and formation history. Perhaps we wouldn't consider the Earth to be a planet if it was out by the Kuiper Belt, but part of the issue is that you're not going to form something like the Earth out by the Kuiper Belt.

livetta — February 8, 2009

I had always argued in my high school science classes back in the 90's that Pluto ought to be re-classified as a Kuiper Belt object-- socially speaking, this endeared me to my teachers, while it targeted me for teasing as a "geek" by my peers. Then the reclassification occurred, and what floored me was that as pointed out, it was viewed as a "demotion," AND when I joked about it, making silly quips like, "Vindication at last!" and other equally ridiculous things, I actually strained friendships. Over Pluto. I find it kind of bizarre how personally many folk have taken the whole issue-- bizarre and fascinating. What does that say about the things Americans were taught in school, and how people (or maybe just Americans) cling to certain worldviews as they were presented early on?

Sociological Images » SAVE PLUTO!: SCIENTIFIC CONTROVERSIES | www.dwarfs.ca — February 9, 2009

[...] here: Sociological Images » SAVE PLUTO!: SCIENTIFIC CONTROVERSIES Share and [...]

Laurel Kornfeld — February 10, 2009

Becky, most of the icy objects in the Kuiper Belt are tiny, shapeless asteroids. The few largest ones, including Pluto, Haumea, Makemake, and Eris have one crucial feature that distinguishes them from the other objects in the Kuiper Belt. They are spherical, meaning they are in a state of hydrostatic equilibrium. This happens only when an object is large enough for its own gravity to pull itself into a round shape. Spherical objects behave geologically like planets, not like shapeless asteroids. That is why we need to differentiate these large objects from the majority of Kuiper Belt Objects.

What is wrong with having a solar system with 20 plus planets? Again, I ask, why not just make dwarf planets a subcategory of the broader term planet, to refer to small round objects that are not located in belts but are large enough to become spherical and therefore have more in common with planets?

Elena — February 10, 2009

What is wrong with having a solar system with 20 plus planets?

That I pulled that number out of my sphincter and I grossly underestimated it. Make it a solar system of 50-400 planets, then.

"As of late August 2006, 44 objects this size or larger in the Kuiper belt (including, of course, Eris and Pluto), and one (Sedna) in the region beyond the Kuiper belt. In addition our large ongoing Palomar survey has detected approximately 30 more objects of this size which are currently undergoing detailed study.

We have not yet completed our survey of the Kuiper belt. Our best estimate is that a complete survey of the Kuiper belt would double this number.

For now, the number of known objects in the solar system which are likely to be round is 53, with the number jumping to 80 when the objects from our survey are announced, and to ~200 when the Kuiper belt is fully surveyed."

Anonymous — January 16, 2010

i think pluto should be a planet!!!

Shawn Prendergast — July 7, 2010

Pluto is a planet. And it was named after the dog, not visa-versa. The fact that millions of people, especially children, are raging about the travesty being foist upon humanity by demoting Pluto just shows that science is NOT about numbers and facts and cold, lifeless stoicism; it is about curiousity, and dreams, and hope of understanding and bettering oneself. Einstein did not say to himself "I must extend the concept of velocity to extraordinary speeds so that we may have a greater range of predictive power"; he *wondered* and *imagined* what it would be like to travel at the speed of light. Newton looked at the sky and, marveling at God's work, and said "How did He do that?". The almost childlike concept of How Small Can Things Go and Can I Break That Apart drive particle physics. The demotion and violation of Pluto is not a scientific achievement, it is a blow to science in the hearts of us all, especially the children. Science is no longer science when we remove the wonder, the surprise, and the joy. That is what the IAU (or the subset that pulled off this coup) has attempted to do. They in fact are the Luddites, mired in concrete black and white prejudices and unable to imagine, to conceive, to create. Science was dealt a serious blow the day Pluto the planet died. I hope the children are resilient enough to withstand this assault, rally, and march over the graves of those who'd leave us in the dark ages once again. Vive la Pluto!