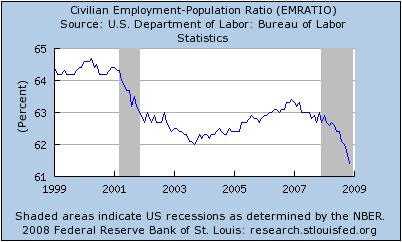

If there are any method-heads out there who want to tell me this isn’t as bad as it looks, I’m ready to listen.

Actually, I just thought of one. The line looks like it drops to the bottom, but the scale starts at 61 and ends at 65. Even still… method-heads?

Comments 10

Benjamin Lobato — December 14, 2008

I think this data would be more useful if years before 1999 were included. 61.5% may be bad, but how bad is relative to the last 50-100 years? That employment is the lowest its been since 1999 I doubt is very surprising to most people.

Daniel — December 14, 2008

I agree. 1999 was probably a local high water mark for employment. My guess is that we are still pretty high when compared to the 70s/early 80s.

Penny — December 14, 2008

Here's the longer view, since the 1940s--big difference in perspective.

http://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/series/EMRATIO/

Benjamin Lobato — December 14, 2008

Good find Penny.

With that context, we can see that our recession hasn't been any worse for employment than similar recessions in the 70s and 80s; at least not yet...

Gwen — December 14, 2008

Although I do wonder--did the data from the 40s-60s count adult women who stayed home full-time as unemployed, or did it ignore them as not really part of the workforce? Because if they were counted as people who could have been employed but weren't, the lower rates back then could partially be a result of adult women's lower rates of workforce participation compared to today.

I have no idea if this was the case, it's just a question about the methodology of counting "civilians" who were or weren't employed.

Penny — December 14, 2008

Right--the women who were out of the paid workforce were not (and are not) counted among the unemployed or the employed--they're neither, for economic purposes. But the point of this ratio is to show how many people are working (and thus paying income taxes) as a proportion of the whole. The reason for the unemployment of the rest doesn't change the ratio--the Y-axis only shows how many paid (civilian) workers there are per 100 residents.

Dubi — December 14, 2008

Penny - yes, but the significant rise between the 70's and the 90's can at least partially be explained by the entrance of more women into the "employed" column. This could go against interpretations that "this is still much better than the 70's", because the breakdown of the "not employed" column has changed considerably.

Of course, all this tells us is that Lisa's graph (or even the extended graph you found) tell us precious little about what I believe Lisa's interested in.

Penny — December 14, 2008

Right. The very simplistic "this is still much better than the 70s" interpretation doesn't take into account that the not-employed population doesn't include as many employable people (meaning, we're closer to maxing out the people who could potentially become income tax payers), and also that the "employed" percentage probably includes more people with crummy jobs (thank you Walmart) and fewer benefits, which means they're paying less in income taxes, etc. etc.

So we still have reason to be very, very concerned about the economy, obviously; but that concern shouldn't be triggered merely by a line graph that's been cut to exaggerate the drop (from a record high). A single ratio is seldom very useful in isolation--interesting, provocative, but still just one slice of a complicated picture.

Pete Murphy — December 17, 2008

This isn't surprising to me and I predict that the ratio will continue to decline. I am the author of a book titled "Five Short Blasts: A New Economic Theory Exposes The Fatal Flaw in Globalization and Its Consequences for America." To make a long story short, my theory is that, as population density rises beyond some optimum level, per capita consumption of products begins to decline out of the need to conserve space. People who live in crowded conditions simply don’t have enough space to use and store many products. This declining per capita consumption, in the face of rising productivity (per capita output, which always rises), inevitably yields rising unemployment and poverty.

This theory has huge implications for U.S. policy toward population management. Our policies that encourage high rates of population growth are rooted in the belief of economists that population growth is a good thing, fueling economic growth. Through most of human history, the interests of the common good and business (corporations) were both well-served by continuing population growth. For the common good, we needed more workers to man our factories, producing the goods needed for a high standard of living. This population growth translated into sales volume growth for corporations. Both were happy.

But, once an optimum population density is breached, their interests diverge. It is in the best interest of the common good to stabilize the population, avoiding an erosion of our quality of life through high unemployment and poverty. However, it is still in the interest of corporations to fuel population growth because, even though per capita consumption goes into decline, total consumption still increases. We now find ourselves in the position of having corporations and economists influencing public policy in a direction that is not in the best interest of the common good.

The U.N. ranks the U.S. with eight third world countries - India, Pakistan, Nigeria, Democratic Republic of Congo, Bangladesh, Uganda, Ethiopia and China - as accounting for fully half of the world’s population growth by 2050.

If you’re interested in learning more about this important new economic theory, I invite you to visit either of my web sites at OpenWindowPublishingCo.com and PeteMurphy.wordpress.com where you can read the preface, join in my blog discussion and, of course, purchase the book if you like. (It's also available at Amazon.com.)

Please forgive the somewhat spammish nature of the previous paragraph. I just don't know how else to inject this new perspective into the overpopulation debate without drawing attention to the book that explains the theory.

Pete Murphy

Author, "Five Short Blasts"

Dubi — December 18, 2008

Pete, pardon my laziness, but I'll just comment on the description you gave here:

I don't understand why population density should bother consumerism. As long as people have money to consume, they can. Long gone are the days when consuming meant purchasing large, long-lasting physical things. Now, if what we consume isn't electronic to begin with (music, movies, games, even books are beginning to go the way of digitization), most of it is disposable. We don't have those old hefty blades for shaving - we have small disposable blades that we have to keep purchasing. My kid hardly has any of those large toys I used to have as a kid that survived through three brothers. He has a million plastic toys that survive just as long as his attention span and are constantly replaced, because they're so damn cheap (and I'm so damn poor). So consumerism seems only to gain from our lack of place to store stuff.