One topic we cover in my sociology classes is the way the nature vs. nurture debate treats those two categories as though they are completely separate entities: “nature” is this fixed biological reality and “nurture” is all the social stuff we use to tinker around with nature as best we can. I point out to students that biology isn’t as fixed as we often think it is, and that seemingly “natural” processes are in fact often highly influenced by social factors.

One good example of this is the age at which girls have their first periods (menarche). In the U.S. today, the average age at menarche is a little over 12 years (see source here), and that seems normal to us. But historically, this is odd; until quite recently, girls did not begin menstruating until well into their teens. Because girls have to develop a certain amount of body fat in order to menstruate, access to food affects age at menarche. And access to food is generally an indicator of all types of social factors, including societal wealth and the distribution of wealth within groups. In general, economic development increases access to sufficient levels of food, and thus reduces average age at menarche.

This graph of average age at menarche in France from 1840-2000 (found on the French National Institute for Demographic Studies website here) shows a clear decline, starting at over 15 years and now standing at under 13:

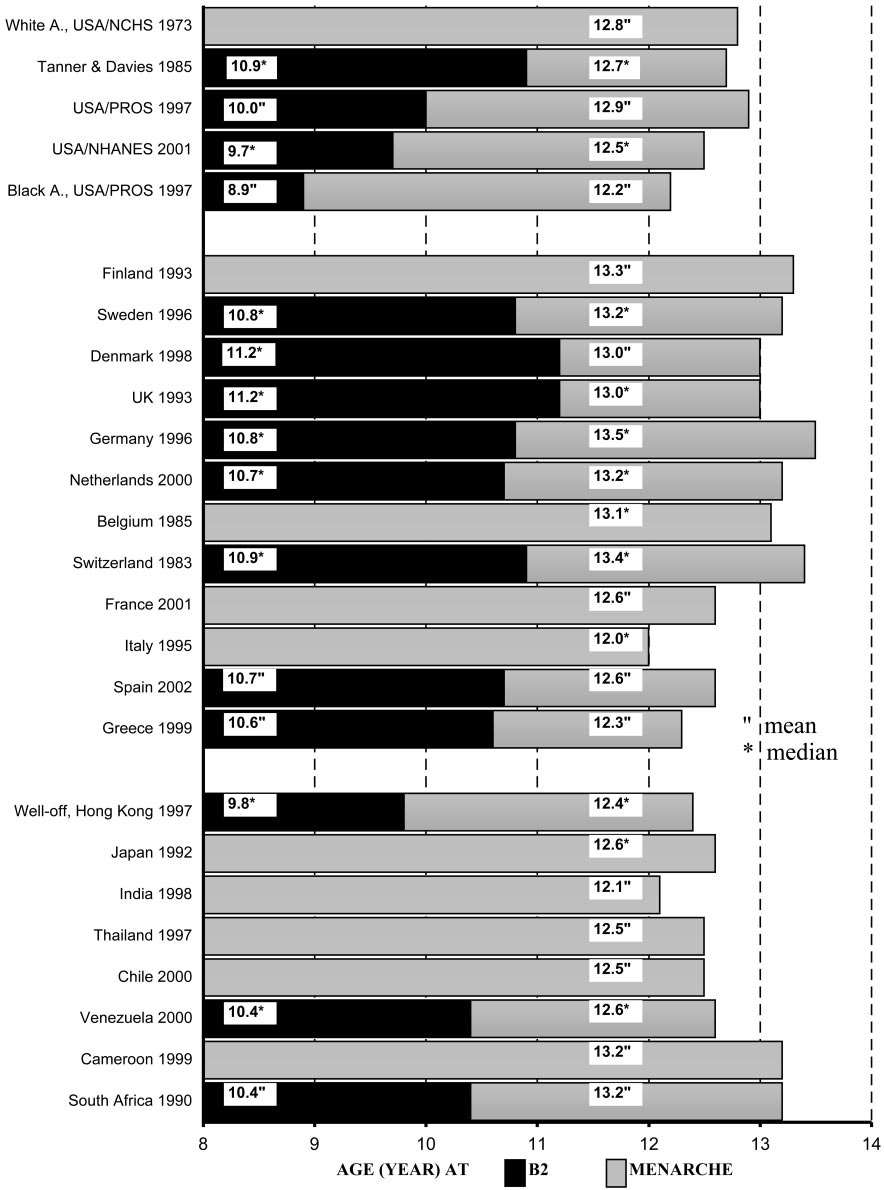

Below is a bar graph showing average age at menarche for a number of countries (found here; age at menarche is the grey bar); we see the oldest average age is 13 and a half years, in Germany. Note that the data are not all from the same year, and while most report mean age at menarche, some report median age, so though they show a general trend, they are not stricly comparable:

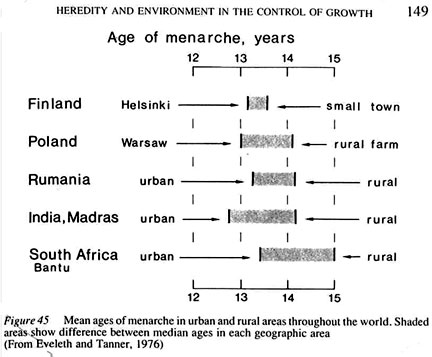

However, these average ages obscure the fact that access to resources is not equal within nations, and as we would expect, though average age at menarche has fallen for most nations over the past century, we continue to see differences in average age among groups within nations that seem to mirror differences in wealth. For instance, this graph (found at the Museum of Menstruation website here) shows differences in average age at menarche between urban and rural areas in several countries:

The example of the quite dramatic fall in average age at menarche, as well as continued differences within societies, is a very helpful example for getting across the idea that biology is not fixed. I explain to my students that though we have many biological processes (i.e., the ability to menstruate), social factors such as economic development and social inequality affect how many of those processes are expressed (i.e., how early girls being to menstruate, on average). For other examples of how social factors affect biology, see this post on average lifespan and this post on increases in height over time.

I’m currently pairing these images with the chapters “The Body’s New Timetable: How the Life Course of American Girls Has Changed” and “Sanitizing Puberty: The American Way to Menstruate” from The Body Project: An Intimate History of American Girls, by Joan Jacobs Brumberg (1997, NY: Vintage Books) in my women’s studies course. Brumberg argues that the decreasing age of menstruation has created new social pressures as there is an increasing gap between girls’ biological maturity (that is, being able to get pregnant at age 12 or so) and their mental and emotional maturity (they’re still 12 year old girls), a point activists were trying to make in these misguided PSAs about statutory rape. Brumberg argues that just as this was happening, American cultural understandings of menstruation turned it into a hygiene problem, not a maturational milestone, meaning we give girls information about tampons and sanitary pads but not much about what these changes really mean.

Just for fun, here is “The Story of Menstruation,” an animated cartoon put out by the Disney company in 1946. Millions of girls learned about menstruation from it in the ensuing decades, including that they could throwing their schedules off by getting too emotional or cold and that it’s ok to bathe as long as the water isn’t too hot or cold. It illustrates Brumberg’s point about how discusses of menstruation turned to scientific explanations of what was happening and advice about what was and wasn’t ok to do while menstruating, while mostly ignoring it’s emotional or social significance.

I also like the explanation at the beginning of why we refer to “Mother” nature–because she does all her work without anyone even noticing, just like moms. How nice.

Comments 23

Lisa Wade, PhD — September 19, 2008

Wow. Terrific post, Gwen!

Dubi — September 19, 2008

A. Due to pollution, there have been increasing reports (in Israel, at least) of menarche (seriously? men-arche?) in girls as young a 7 or 8 years old, along with other signs of physical maturity. From what I've heard, it's become a concern that prompted some agencies to try and provide girls with such premature puberty with treatments that delay it into the teens. Obviously, third graders who need bras suffer quite a lot at the hands of their peers.

B. I should note that in the life sciences, nobody really thinks there is any strict separation between nature and nurture. The general understanding is that "nature" (i.e., genes) provides a range within which the actual phenotype is determined by "nurture" (i.e., everything else). It just feels like one of those things where sociology keeps debating issues that were raised and discredited by the life sciences decades ago.

Gwen — September 19, 2008

Dubi--Yeah, there's worldwide concern with early puberty. There seemed to be this "biological floor" of 9 years old as the earliest, but now there are concerns that pollutants are overcoming that.

And my statements about the nature/nurture debate weren't directed at other scientists--but the general public, or at least that part represented by our students, seem to have a very simplistic idea of how genes work. They'll ask me if there's "a gene for athletic ability," as though there's just one gene that, if you have it, makes you good at any and all sports and if you don't, means you suck. So I find myself having to really work to get them to think about biology and genes in a more complex way and to stop thinking that individual genes work in isolation and "make" you do this or that.

Fernando — September 19, 2008

I don't see much how these specific examples fit in the nature vs nurture discussion. I mean, obviously what we eat and breath, which is product of what we do, affect our bodies in many different ways. From my understanding the discussion of nature vs nurture is around issues related to our behaviors, talents, tendencies.

Gwen — September 20, 2008

Part of the issue is that the nature/nurture debate is set up as a one-way street: biology limits what we can do through socialization, but there's no comparable way in which social life affects biology--biology is set, fixed, determined at birth, because it's genetic. So we are essentially animals, and then we can mess around a bit with culture (say, trying to teach men to control their "natural" violent urges, etc.). The graphs don't just show "the environment" affecting biology; they show human society, and particularly economic inequality, affecting a biological process.

Those changes in a biological process have then created social changes as well--for instance, passing statutory rape laws to deal with the fact that we now have young girls able to get pregnant but whom we define as too emotionally immature to be having sex.

I use examples like this to try to get students to think about how, if biology and culture are so intertwined regarding something like menstruation, which seems very simple, and if social factors can influence it, then the idea that something like athletic ability or aptitude at math or other complex talents or behaviors is "simply" biological is questionable. They honestly seem to think there is "a" gene for any behavior/trait (as opposed to lots of genes working in various ways). And I have to do a lot of work to get them to even possibly admit there might not be, say, "a gene" for math that explains why Asians in the U.S. tend to have higher standardized math scores than other racial groups.

Anonymous — September 27, 2008

Why is the baby wearing lipstick and mascara?

Carolyn Dougherty — August 3, 2010

A while ago I asked one of the Vikings at Jorvik about the practicalities of child marriage--given that the age of menarche has been dropping, wouldn't girls 1000 years ago not have been sexually mature until their mid teens? Apparently not--the Vikings had access to lots of high-protein fish, and both men and women lived healthy active lives, so the girls did indeed start menstruating as young as we do. The high age of menarche in the 19th century (as well as the short stature and other indicators of poor health) had to do with the wretched living conditions for most Europeans after the start of the Industrial Revolution.

AitchCS — January 17, 2011

The addition of artificial light in our lives so many hours in the 24 hour cycle---lights in the home or office and night--not natural darkenss--has contributed to the earlier age of menstruation. One theory.

Darkwing Duck — April 26, 2011

"a useful record of past performance." *snerk* *snort* Yep. My period. It's a performance.

Anonymous — May 27, 2012

Another possible factor for earlier menstruation that I noticed was not mentioned was exposure to synthetic chemicals [generally endocrine disruptors]. Although I guess that's generally not covered in sociology...?

And Coerced Abortions for the Trifecta! - Page 6 - SLUniverse Forums — June 28, 2012

[...] [...]

The CultureWars and Your Aunt Flo | Away Point — July 17, 2012

[...] the 19th Century there was approximately a five year gap between when females started their periods and age at first marriage; now the gap is closer to fifteen years, with many girls [...]

A Brief History of Your Period, and Why You Don’t Have to Have It | Femina Invicta — July 25, 2012

[...] the 19th Century there was approximately a five year gap between when females startedtheir periods and age at first marriage; now the gap is closer to fifteen years, with many girls [...]

Víkendové surfovanie « life in progress — September 9, 2012

[...] o posúvajúcom sa veku prvej menštruácie … the decreasing age of menstruation has created new social pressures as there is an increasing gap between girls’ biological maturity (that is, being able to get pregnant at age 12 or so) and their mental and emotional maturity (they’re still 12 year old girls), a point activists were trying to make in these misguided PSAs about statutory rape. Brumberg argues that just as this was happening, … cultural understandings of menstruation turned it into a hygiene problem, not a maturational milestone, meaning we give girls information about tampons and sanitary pads but not much about what these changes really mean. [...]

All about periods. | UBC Psychology 350A — September 21, 2012

[...] the 19th Century there was approximately a five year gap between when females startedtheir periods and age at first marriage; now the gap is closer to fifteen years, with many girls [...]

Rosina — January 8, 2014

I know it's not related to sociology per say, but another possible explanation is the increasing use of hormones in our food sources, which would explain why there would be a disparity between rural and urban areas. It is probably more comoon that those who live in urban areas would eat more processed food, whereas the opposite might be true in rural areas.

Why the age you get your period can matter forever | Fusion — August 1, 2015

[…] decline has been seen from first-world to third-world countries—similar stats are reflected from France to India—and across races. (In the U.S., black and Latino girls are most likely to get their […]

tessa — November 18, 2015

Enjoyed reading. I'd also look to not only pcb's, chemicals mostly in canned food and water (endocrine disruptors) but. Also the link between not only early onset puberty and a rise in disease since the mid nineties when gmos were introduced into the food supply. (Genetically Modified organisms) their glyphosate (other pesticides) and growth hormones in the food. Most notably, the U.S. and our pets and livestock too.

Why the age you get your period matters — for the rest of your life: ( by Taryn Hillin ) – redlegagenda — January 23, 2016

[…] decline has been seen from first-world to third-world countries—similar stats are reflected from France to India—and across races. (In the U.S., black and Latino girls are most likely to get their […]

mandy jones — December 3, 2016

Actually menarch doesn't equal being fertizle in most girls.

mandy jones — November 19, 2017

Girls in urban areas seem to start their a little earlier.

Anika Yip — March 4, 2020

We seem to assume that the age of menstruation in the 19th century was the age it was since the beginning of time. As in, the age for menarche has only ever declined. I would be interested to see the age of menstruation prior to that time, rather than only the data from the 19th century, as it’s not right to assume that the age then is the “normal age.”

Emma — January 3, 2022

I thought menarche was connected to body mass. 21st century girls have more mass than even 20th century, hence the ceiling of 9 years old can be breached. Those who have begun menstruating usually stop if they loose sufficient weight to take them under 45kg.

There are hormonal abnormalities that pollutants may affect but hormonal changes fall into the 'disease' category rather than the girls in general menstruate earlier now which I thought was connected to body mass.

I very much appreciate the comment about physical vs social vs emotional explanation of menarche. As a scientist and religious I am thankful that we are beginning to realize that science cannot explain everything. We need more social data and humility.