In this Roundtable, we ask a panel of experts to reflect on a recent Pew Center on the States Survey that found half of Americans believe there are too many prisoners in the U.S. The survey also found that voters believed that one-fifth of prisoners could be released without compromising public safety. In other findings, 48 percent agreed with reducing funding for state prisons and large majorities favored reducing prison time for low-risk, non-violent offenders.

Our Roundtable panelists, while encouraged by the implementation of this survey, were careful not to put too much positive spin on the results. While public support may be moving towards a less punitive America, it’s not certain policy will quickly follow suit.

We began by asking whether anything in the Pew results surprised our respondents. Their answers ranged from near dismissal to cautious optimism.

David Jacobs: There are only a few policies that respond to public opinion, so I’m not very optimistic that [these measures matter]. The conventional wisdom in American politics, or demographic politics, is that public opinion drives policy. But that’s only true about a few issues. If it’s at all complicated, forget it. ….We have a tendency as graduate students and sociologists to think in terms of left-right. You can ask people are they conservative or liberal, and you’ll get answers from them. They’ll be polite and answer your questions. But if you correlate those self-identifications with actual policy or voting, it doesn’t seem to matter much.

Frank Cullen: As someone who has studied public opinion for thirty years, I am not overly surprised by any of the findings. I am heartened that the survey was undertaken, however, because it shows that the American public holds reasonable views about crime-control policy. Its members realize that mass incarceration is not a sustainable policy and is not appropriate for all offenders.

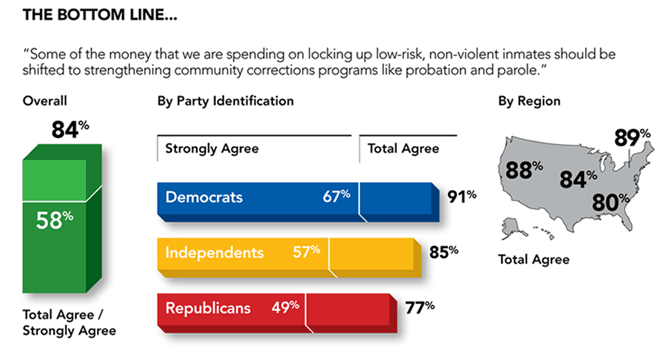

Jeremy Travis: Perhaps the most important finding of the Pew Survey was the bottom line—nearly half of those surveyed thought there were too many prisoners in America, and nearly half thought prison budgets could be reduced. For elected officials—and candidates for office—who have thought that the public would not support criminal justice reforms designed to reduce the size of our prison populations, these survey results should give them confidence in moving forward. What is more impressive however, are the survey findings that the public wants a more effective criminal justice system, not just a less expensive one. …The public official seeking to cut back on the levels of incarceration would be well-advised to propose an alternative investment strategy for the savings—preferably one that would enhance the justice system.

David Garland:* The American people are right to think that we punish too many people and we have too many people in prison. And it’s good [to see in these results] that they’ve caught up with that fact. On the other hand, it’s the American people and their representatives that have created that situation and my guess is that many American people polled in these opinion polls will say that we punish too many people for too long, but the particular offender who just burgled my house or raped my neighbor’s daughter or robbed this store, they deserve to never be let out… So there’s a disjuncture sometimes between the abstract opinion and the particular one.

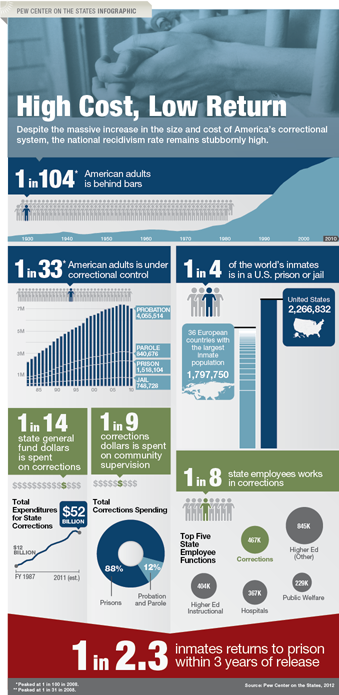

However, I have to say that I’m deeply pessimistic—to the point of being depressed—about the following fact: …the mass imprisonment system that’s been built up in America is one of world-historic proportions. No nation of any description (but certainly not a liberal democratic nation) has ever before had a carceral system in which 750 per 100,000 people are incarcerated. The equivalent in Europe is about a sixth of that, a seventh of that, sometimes a tenth of that, and I really don’t see how the United States of America can move toward having normal rates of imprisonment in any time period that one can envisage. …The build up has taken forty years. To get back to [our even comparatively high rates of incarceration in the ‘70s], it’s hard to see how it can take less than forty years.We then asked whether our experts could speculate as to the causes of the opinion shifts found in Pew’s poll. Could we point to politics, economics, or cultural changes that might lead to a new outlook on crime and punishment?

Cullen: I do not believe that public opinion has shifted at all—or, in the least, that much. I think that what has shifted is the questions that are asked in the surveys. For example, public support for rehabilitation has remained high for three decades… the public has long made reasonable judgments. They want offenders who are dangerous to be incapacitated in prison. While they are there, they want efforts undertaken to rehabilitate them. They will support community-based sentences for many offenders, so long as this includes appropriate supervision and treatment. What they do not support is irresponsible decision-making, where dangerous offenders are released inappropriately or where offenders are placed in the community with little intervention.

Jacobs: Crime rates are down, maybe people aren’t as threatened by [crime]. The Republicans also no longer campaign on crime, probably because it doesn’t work anymore. There is also a connection to [the amount of] media attention [paid to crime]…

Garland: It has to be said that the remarkable diminution in crime rates, sustained over several decades now, has made crime less of an emergency, urgent, top-of-the-agenda issue for many people in this country. That’s not to say that crime rates in this country are low: homicide rates are still four or five times that of any other liberal democratic industrialized nation. On the other hand, crime is less pressing as an issue and crime rates have come down considerably. Our cities—many of them—are safer. Not all of them, but where I live in New York City, it’s considerably safer. For these reasons, I think, the relaxation of punitive energy and enthusiasm is to be expected. The build-up of a massively extensive penal apparatus (prison system, jail system, probation system, parole system) in which there are 7.5 million people on a daily basis, that of course is an enormously expensive undertaking. And, at a time of fiscal stringency s where teachers …and police officers are being laid off, of course politicians …and the public are beginning to consider [whether] we were a little extravagant in our use of penal resources and prisons and does everyone need to be in there forever?

Travis: The nation is witnessing a gradual shift in attitudes regarding our response to crime. The best indicator of this shift can be seen in our juvenile justice system. Twenty years ago, during the rise of juvenile violence in the 1980s, young people were demonized in our public discourse. Some experts said we were witnessing a generation of “super predators,” and warned of a coming bloodbath. In this atmosphere, we passed laws severely punishing young people for their crimes. As a result, the number of youth in prison climbed to historic high levels. Now, we are witnessing a remarkable decline in the number of youth in detention and placement facilities. We are seeing a similar shift in public attitudes toward the death penalty, as 18 states have outlawed capital punishment, and the number of executions has dwindled.

Unfortunately, the winds of change have not yet swept our system of adult prisons. Granted, the nation has seen small declines in rates of incarceration and some states have seen their prison populations drop by as much as twenty percent, but we still incarcerate our population at rates far higher than any other country. The reason for these shifts? The decline in crime is the most important factor… But there is another force at work—our crime policy is becoming more pragmatic, more focused on problems, less ideological. Community policing, problem-solving courts, the reentry movement, the emphasis on “best practices” and “evidence-based policies”—these developments hold great hope for the future. Finally, the nation is coming to grips with the deleterious effects of our criminal justice policies. The revelations of hundreds of wrongful convictions give us pause about the efficacy of the criminal justice system. And the heightened awareness of the devastating consequences of our justice system for communities of color provides a strong impetus to reduce the harms we cause.

When we turned to considering what actual changes in imprisonment policies, and even release programs, might mean for the public, Frank Cullen pointed out a historic parallel and its unintended consequences.

Cullen: The difficulty is in seeing prisons as the answer to the crime problem. Research is clear in showing that placing an offender in prison is not more effective in reducing future recidivism than a community-based penalty. Mostly, the savings that accrue from imprisonment is the crime saved while an offender is behind bars. Given this reality, it makes sense to imprison only high-risk offenders (or those whose crime is so serious that punishment by prison is deserved). A crucial issue is not simply who is or is not sent to prison, but rather what else we do while an offender is within our grasp. Simply put, the correctional system should “correct.” There is a growing literature on what works to rehabilitate offenders….Finally, a massive release of prisoners would, by itself, be irresponsible policy. To be responsible, we should, first of all, refrain from sending low-risk offenders to prison [in the first place]. Then, we should release …those offenders who are low-risk—either because they were never high-risk or because their risk levels have been lowered through treatment programs. [And], for those released after [serving their time], we should ensure that effective reentry programs are established …that they receive appropriate supervision that includes not only surveillance but also treatment.

We do not wish to repeat the errors that occurred when patients in mental hospitals were deinstitutionalized in mass numbers—too often [they were released to lives of] no services and, for too many, to lives of despair and/or homelessness. Anything we do in the criminal justice system should be done responsibly.

Travis, too, urged cautious, carefully planned changes in carceral policy.

Travis: …Advocates for lower levels of incarceration have often said, “Now the prison system has finally gotten too expensive, and our elected officials will finally see the error of their ways and reduce the prison population.” For forty years, this prediction has not been borne out. On the contrary, … in the face of ever-expanding prison populations and corrections budgets, our elected officials have been willing to pay the bill. And they have been supported by the public.These survey results do not help public officials consider the potential costs and benefits of a program of large-scale releases of prisoners [because] the questions in this survey are based on various policy alternatives and assume the policy maker is operating in a world of considered decisions. A large-scale release program poses enormous risks… the near certainty that someone released early will commit a serious crime. Perhaps the public will be understanding and recognize that this crime could also have occurred at a later date, when the release was originally scheduled. But, more likely, the public will view this as a crime that [would] not have occurred, and will hold the government official responsible. So early release programs should be considered with great caution. This concern also argues for the “balanced portfolio” concept—so that the public will see the advantages of alternative investments.

Our final question was broader, going beyond the specifics of this recent Pew Survey to ask whether public opinion matters for policy makers more generally. If, then, the public responds in a well-rendered poll that they largely believe in a reformation of the nation’s approaches to punishment, will we begin to see change as eager politicians respond to their constituents?

Our final question was broader, going beyond the specifics of this recent Pew Survey to ask whether public opinion matters for policy makers more generally. If, then, the public responds in a well-rendered poll that they largely believe in a reformation of the nation’s approaches to punishment, will we begin to see change as eager politicians respond to their constituents?

Cullen: A survey [like Pew’s] can matter a great deal. Policy makers are not necessarily driven to act by public opinion surveys, but they are unlikely to pursue reforms if the public is seen as opposed. Policy makers generally overestimate the punitiveness of the public, [so this] is crucial in showing policy makers that they have considerable latitude in devising reasonable policies.

Jacobs: There is work in political science that shows that the correlation between the attitudes of voters and congressional votes on policy issues vary by the policy. Most voters don’t know anything about foreign policy, for instance, so there is no correlation. For economic policy, spending and things like that, there is a modest correlation. The only strong correlation you get between constituents’ attitudes and congressional votes is about highly symbolic issues, like civil rights, abortion, or capital punishment. So, I don’t see [this survey] as very consequential because for most public policies, public opinion doesn’t matter. There is no evidence that [public opinion matters for] a very sophisticated policy, like a collection of laws that increase imprisonment or …imprisonment spending….

Travis: The question now is whether the public mood has turned, [if] the public now believes the prison budget can safely be reduced. [Pew’s] survey results would suggest that this shift is possible. But it is too soon to know for certain. …So the question of the moment may be how best to capture the public mood—when the public is looking for a more balanced investment portfolio with reductions in prison budgets and increases in community supervision budgets—to map out a long-term strategy rather than seeking quick results through a program of early releases.

Garland: I [recently attended] a very powerful, inspiring social activist speech by Michelle Alexander…, the author of a book called The New Jim Crow, which …argues, I think powerfully (if unpersuasively) that …the system of mass confinement, which has been disproportionately suffered by black men (increasingly, by black women, too), will not be undone by the kinds of legal reforms that are currently envisaged. It would take a social movement on the scale of the Civil Rights Movement to undo it. And I think that she is right about that, but I think there’s no prospect whatsoever of a social movement of that kind.The punishment of criminal offenders is not an unpopular position, nor is it even a position that violates the values and the Constitutional commitments of the American liberal, the American Democrat, or American civil liberties. It’s a matter of scaling back excessive punishment, and I think that will only ever get done through the realization by legislators and by elites that rendering punishment questions as populist questions was a huge mistake. Because the answer will always be, “More, please!” We’re talking about what to do with violent offenders, dangerous offenders, but even drug offenders who might one day be violent and dangerous or who might be selling their drugs to “our children.” The popular response, by and large, is “Lock them up. Let me not see them on my street, please.” For that reason, it’s very, very difficult to see a widespread social movement mobilized for and on behalf of criminal offenders.

That’s a desperate reality, because the tragedy of American imprisonment can’t be understated. It’s been devastating for not just the men and women involved, but for their communities, for their spouses, for their families, for their children, for their neighborhoods, and for the states in which they live.

*A note: David Garland’s responses were taken, with his permission, from the transcript of his Office Hours interview with The Society Pages. To listen to the entirety, click here.

For more on polling in general, please read the recent TSP Roundtable “Polling, Politics, and the Populace,” with Paul Goren, Howard Schuman, and Tom Smith.

Comments 3

Chris Uggen — August 8, 2012

Terrific roundtable, Sarah, with really thoughtful commentary. I see some consensus across the responses about ramping down criminal punishment. Like Frank, I'm concerned about the mechanics of responsible decarceration -- the public safety record of some "early release" evaluations has not been reassuring.

Sarah Lageson — August 14, 2012

Reducing the prison population is also clearly easier said than done - for instance, the LA Times reported this week that California is behind on their federal mandate to reduce its prison population. The LA Times reports:

"In May 2011, the high court gave California two years to comply with the three judges' determination that prisons should not be overcrowded by more than 137.5%. State officials concede they are unlikely to reach that target by the June 2013 deadline and have told the judges they intend to ask for a new cap of 145%."

Source: http://www.latimes.com/news/local/la-me-prisons-20120811,0,6752352.story

Dudley Sharp — September 28, 2012

The 5 Myths of Prof. David Garland – death penalty

Dudley Sharp

It is difficult to say if Prof . Garland is just sloppy or if, like many in academia, he is happy to peddle bias in service of a goal, here, an end to execution.

(“Five myths about the death penalty”, By David Garland, July 18, 2010, http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2010/07/16/AR2010071602717.html)

Lets’ look at Garland’s myths:

1) Garland fails to mention that it is the judges that make the imposition of the death penalty all but impossible in some jurisdictions. Dictatorial judges in New Jersey never allowed an execution. There, the death penalty was repealed. Pennsylvania judges never allow executions other than those whereby the inmates waive appeals. If you appeal a death sentence in Pa, you have a life sentence, even if your death sentence is not overturned. Similar abusive judicial behavior is legendary in California.

The death penalty in Virginia? Inmates are executed within 7.1 years, on average, after sentencing, 75% of those sentenced to death have been executed and only 15% of death row cases are overturned on appeal. The national averages for those are 11 years, 13% and 37%, respectively.

The difference is in the judges.

Victim survivors in death penalty cases are knowingly and unnecessarily tortured by such irresponsible and callous judges, as in NJ, Pa and Ca and others, nationwide.

Garland gives the false hope that by replacing the death penalty with a life sentence that we can avoid these problems. All states are, now, looking at ways to release lifers, early, for overcrowding and cost issues.

Instead of the abusive performance of judges in so many death penalty jurisdictions, cases, abuse which should be stopped, those murder victim survivors would then be served a recurring theme of releasing those lifer murderers of their loved ones.

The same legal challenges that have been used for years to restrict death penalty applications, are now being repeated in challenging life sentences. Pro death penalty folks have been stating that pending course for years and it is now in full swing. Murderers serving life sentences can appeal for life.

2 and 3. Yes, fortunately, American democracy is stronger. Even in Europe, the collection of countries whose governments are most opposed to the death penalty, the majority of their populations do support the death penalty for some crimes (1). Those governments could care less.

It may be the case that a majority of citizens in every country support executions for some crimes, based upon the proposition that such sanction is a morally just and proportionate sanction for the crime(s) committed, the foundation of support for all criminal sanctions.

The insult here is that Garland believes that governments ban the death penalty because they know better, that they are wiser than those whom they govern, similar in fashion to the dictatorial judges who confound the law, as reviewed. In fact, it is simply a product of Garland’s bias, with no evidence to support it and a false sense of parental superiority guiding it.

4. Predictably, Garland says “it stretches credulity to think that the death penalty, as administered in the United States today, can be an effective means for deterring murder”.

Note, that Garland’s hedge is “effective”, which he can define in any manner he wishes.

Of course the death penalty deters. All prospects of any negative outcome deter some. There is no exception.

Let’s say that only 0.5% of murderers are deterred every year because of deterrence. It is a very small percentage of murders deterred, but huge in terms of lives saved, about 90 innocents saved per year, on average, since 1977, noting an 18,000 murders/yr. average during that time.

Is that effective, enough, for Garland? Probably not. For many against the death penalty, it wouldn’t matter if a thousand lives were spared per execution because of deterrence, they would still seek its end.

Of the recent (since 2000) 28 studies finding for deterrence, there is a range of deterrence detected, between 1 and 28 lives spared per execution (2), with an average of about 30 executions per year, since 1977, which equates to about 30-900 innocents spared per year because of deterrence.

Garland states that “66 percent have their death sentences overturned on appeal or post-conviction review. He needs to fact check. It is 37%. (3)

Garland states that “a smaller number — 139 — have been exonerated in the past 30 years”. Fact checking is definitely not Garland’s thing. The 139 exonerated is well known fraud and easily uncovered by anyone who cared to fact check. (4)

5. Of course the death penalty works. Everyone who has been executed has remained dead.

Garland states: “An Indiana study last month showed that capital sentences cost 10 times more than life in prison without parole.”

Not surprisingly, Garland didn’t fact check that story either. It is about 12% more expensive not the 1000% (10 times) that Garland found. (5)

Garland closes: “Getting past the myths and looking at how the death penalty actually operates is one place to start. ”

How would he know?

1) “Death Penalty Support Remains Very High: USA & The World”

http://prodpinnc.blogspot.com/2009/07/death-penalty-polls-support-remains.html

2) 28 recent studies finding for deterrence, Criminal Justice Legal Foundation

See Published Research, Working Papers and Essays at http://www.cjlf.org/deathpenalty/dpdeterrencefull.htm

3) “A Broken Study: A Review of ‘A Broken System’ ”

http://prodpinnc.blogspot.com/2009/10/broken-study-review-of-broken-system.html

4) “The 130 (now 139) death row ‘innocents’ scam”

http://homicidesurvivors.com/2009/03/04/fact-checking-issues-on-innocence-and-the-death-penalty.aspx

5) Garland was referencing a review that didn’t look at all the costs and stated that it didn’t include all the costs. With one exception, this one appears to.

See Background Information, page 2, Fiscal Impact Statement, Legislative Services Agency,

http://www.in.gov/legislative/bills/2008/PDF/FISCAL/HB1074.004.pdf

Costs per case

$758, 243 for death penalty

$657, 028 for LWOP

However, this excludes the credit of savings for plea bargain to LWOP, which I suspect saves at least $20, 000 per case, solely attributed to having the death penalty.

That would bring the differential down to about $80,000 – the death penalty and LWOP cost amounts are already present valued.

$738, 000 for death penalty (inclusive of LWOP plea credit cost savings, solely attributable to having the death penalty)

$657, 000 for LWOP

The death penalty is 12% more than LWOP.