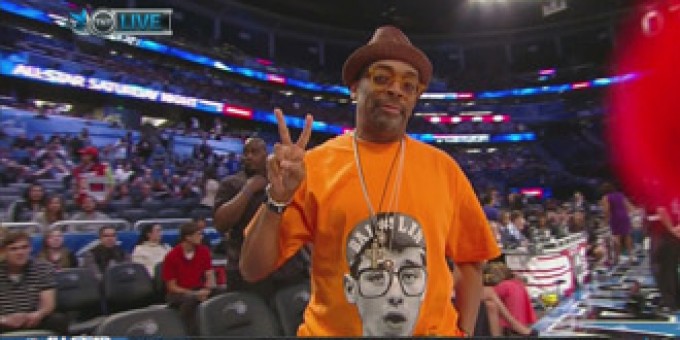

In February, New York Knicks point guard Jeremy Lin seemingly came out of nowhere to propel the struggling Knicks to seven straight victories. Suddenly, the Knicks were relevant again and “Linsanity” was in full force. Drafted in 2010, Lin is the first Taiwanese American to play in the NBA and the first Harvard graduate to do so since the 1950s.

Now, just a few months removed from this improbable craze, Jeremy Lin has all but disappeared from the public radar; he will likely miss the remainder of the NBA season with an injury. We rounded up three leading scholars on race and sports to reflect upon Jeremy Lin’s stint as a media sensation.

First, we asked the simple question: why all the fuss about Jeremy Lin? Rosalind Chou answers:

Chou: He’s surprising people because he doesn’t meet the stereotypes of Asian American men. His popularity among Asians and Asian Americans who aren’t fans of the NBA has something to do with pride and, in some ways, relief. Pride in the fact that someone of Asian descent has broken racial barriers and is disrupting the hegemonic masculine hierarchy.

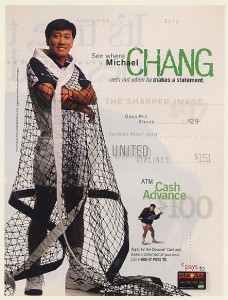

The relief is based on the fact that, finally, there is a public Asian American male figure that gets to retain his manhood. The way masculinity is constructed for men in sports organizations like the NBA and NFL are contrary to the stereotypes of Asian and Asian American men. So, in the case of professional tennis player Michael Chang, while he was a successful, top athlete, his success didn’t break racial stereotypes because tennis players aren’t constructed as “manly” or “tough” as professional football and basketball players typically are. The NFL and NBA are exclusive male spaces for the biggest, strongest, men in the country, or even the world. So the media has been running with the Lin story because it seems so impossible and improbable.

C.N. Le explains how some positive stereotypes about Asian Americans—often called the Model Minority image—has negative implications for Asian American athletes:

Le: The model minority image has basically framed Asian Americans as being very good at certain things such as math, science, and educational attainment in general, but has also limited Americans’ views of what Asian Americans can do outside of those “traditional” areas. In other words, Asian Americans can win a Nobel Prize but still struggle to be taken seriously as political leaders or in Jeremy’s case, as professional athletes.

Chou: Lin’s “model minority” status has also been played up with emphasis on his Ivy League pedigree. He’s been called a “smart player” and “student of the game.” Colorblind language has been used to emphasis how “clean cut” he is compared to “tattooed” or “thuggish” other players (implicating black and Latino athletes). I think these media articulations of his race are very much in line with how Asians and Asian Americans are traditionally racialized in the US, with the exception of the emphasis on his devout Christianity. I think in some ways the discussion around his religion “normalizes” and makes him relatable to other Americans.

It’s very similar to the Susan Boyle phenomenon on Britain’s Got Talent. Someone who looked like her couldn’t possibly sing like an angel. Someone that looks like Jeremy Lin couldn’t possibly be a talented basketball player because it doesn’t meet the racialized ideology embedded into our society.

Ben Carrington frames the success of Jeremy Lin’s story in terms of American ideals about sports and meritocracy:

Carrington: It’s undoubtedly the case that the Lin story directly taps into a number of powerful American myths concerning hard work, social mobility and perseverance: the belief that Lin succeeded “against the odds” and that his religious convictions as a devout Christian gave him the faith in his own abilities to keep pursuing his dream of a professional basketball career. Such a story line, that was successfully spun by the sports-media complex, has resonance way beyond the NBA, and in part helps to explain the level of attention he has attracted.

Sports are one of the few arenas in life where people – both sports fans and those who don’t follow sports – are most likely to believe that a meritocracy actually exists, that the best player always gets picked to play and comes first, and that hard work and dedication pay off in the end. People tend to have an idealized notion of sports as free from politics and discrimination thus often there’s an over-investment in what we might call The Myth of Sport as this meritocratic arena. Now, given that basketball, at least in the US, is racially coded as an “urban sport”, played predominately by black, working-class male youth, Lin’s presumed atypicality gives the story an extra “edge”, provides a reversal of sorts, a novelty factor that serves to both reaffirm The Myth of Sport and allow for a series of not always informed discussions about race, difference and identity to take place.

And, of course, he’s playing in New York, not in Utah, so the potential media interest in a story involving a Knicks’ player will be greater. Thus, given all these factors, plus perhaps the desire for a “feel good” sports story in place of the usual drugs, corruption and cheating scandals, the Lin story hit at just the right time.

Amidst the media coverage of “Linsanity,” several incidents brought Lin’s race to the fore. For instance, after the Knicks’ first post-Linsanity loss, ESPN ran a story with the headline “A Chink in the Armor.” Le comments on this episode and media coverage of Lin:

Le: To the extent that his race is mentioned, I think the mainstream media has treated him and his racial identity well. But in most cases, keeping with the prevailing “colorblind” mentality that most Americans (particularly White Americans) have, I think people generally are reluctant to talk about his race and probably feel that it’s “safer” to focus instead on his basketball performance. Unfortunately, it’s also this colorblind mentality and unwillingness to talk about race that leads to racial ignorance. This was exemplified in the ESPN “chink in the armor” episode and how those involved either had no idea or did not care that that particular phrase was offensive when used in reference to Asian Americans. To ESPN’s credit, they reacted quickly and decisively in firing and suspending the employees who used that term (I wrote more about this in a blog post.

Controversy also ensued after boxer Floyd Mayweather claimed “Jeremy Lin is a good player but all the hype is because he’s Asian. Black players do what he does every night and don’t get the same praise.” Carrington points out that Lin’s race has cut both ways: increasing positive attention now, but also in being responsible for decades of discrimination:

Carrington: Floyd Mayweather was of course right, in the narrow sense, when he suggested that while Jeremy Lin was a good player the “hype” around him was largely due to his Asian identity. Race has been central to the coverage. In the US there is no popular notion of “the Asian athlete”. Prior to this year whenever I would ask my students to name a significant and well known Asian American athlete, their answers, after a long pause, would be Yao Ming, “that female golfer”, and sometimes Michael Chang. Well Ming is obviously Chinese and no longer plays in the NBA, the fact that most students can’t even name Michelle Wie is instructive, and Chang retired from top-level tennis nearly a decade ago.

It is also apparent, although the media and the pundits have had a hard time acknowledging this, that the primary reason why Lin was overlooked for so long—when he was a stand-out high school player but was not picked up by any of the major basketball powerhouses at the college level, when he was outstanding at Harvard and yet still not drafted, when he outplayed NBA draft picks in the summer leagues and still didn’t get a professional contract commensurate with his talents, when he was cut by teams after getting limited playing time (and remember he was weeks from getting cut by the Knicks too)—is the fact that he’s Asian. The racial lens through which we read, judge and assess human potential meant that all of these great coaches and scouts and General Managers couldn’t see past Lin’s race, which coded him as anything but a professional ball player.

As my UT Austin colleague Eric Tang puts it, stereotypes regarding Asian American identity produced a kind of blindness that kept Lin “hidden in plain sight.” When people say that Lin “came out of nowhere,” they talk as if he suddenly walked into Madison Square Garden off the streets of Manhattan! Lin didn’t come out of nowhere. He was there the whole time. Playing brilliant basketball. It was the power of race, or more precisely racism, in structuring how we see, what we see and how we make sense of what we see, that led him to be overlooked for so long, until he seized upon his likely final chance to show his talents and he performed to such a high level that his abilities were finally recognized.

Finally, we asked our roundtable participants to predict the long-term impact of “Linsanity”:

Carrington: We simply don’t know. One of the interesting aspects about sports is that (for the most part), we don’t even know how a particular match will end, let alone a professional sports career that has barely started. Lin has already been injured this season and is unlikely to play again. Lin is clearly a very good basketball player, and potentially a great player. But he may also end up being an average player, an injury-prone player, or someone who, like hundreds of others, gets cut and disappears from the public view in a year or two.

I also don’t think we are at a historical moment where we’re about to witness the creation of “the Asian American athlete” like we saw just over a hundred years ago when Jack Johnson became the first black heavyweight boxing champion of the world and who ushered into popular consciousness the idea of “the black athlete.” Lin will probably be defined as the exception. Racial ideology was always been able to accommodate exceptions and contradictions. The crude forms of anti-Asian American racism and stereotyping that have come to the fore in the past few months helps us to see how the simplistic notion that sports dissolve questions of race and racial difference and that we are in a post-racial era is just that, simplistic.

Le and Chou, however, were optimistic that Jeremy Lin’s success could inspire challenges to stereotypes:

Le: As time passes, Lin’s success and prospects for continued success, perhaps ironically, will hopefully be less and less of a big deal. In other words, hopefully his success is a meaningful step toward the ultimate goal of colorblindness—when people will see Asian Americans succeeding in professional sports as “normal” just as it is seen for white Americans and African Americans.

Chou: Jeremy Lin redefines what it means to be an Asian man in the United States. He breaks down racialized stereotypes about Asian American men, about their masculinity, their bodies, about their sexuality, and he provides a role model for any Asian boys or men that have ever been bullied or taunted about their manhood… When I was young, a teacher told me that people who looked like me “were not athletes.” I refused to believe him. Jeremy Lin refused to believe all the people who overlooked him or ignored him… The United States still has problems with racial inequality and racism, but I also believe that we are continuing to progress. My hope is that future generations will see many more stories like Jeremy Lin’s, in which racial stereotypes are being dismantled and discarded, even if just briefly.

Stephen Suh and Kyle Green are graduate students in sociology at the University of Minnesota. They are members of The Society Pages’ graduate student board.

Comments 8

Stephen — April 18, 2012

Jeremy Lin was just named one of Time Magazine's 100 most influential people: http://www.time.com/time/specials/packages/article/0,28804,2111975_2111976_2111945,00.html

Dave from JeremyLinFansHQ — April 21, 2012

Great round table discussion here. While most of the points are pretty obvious in a media standpoint, i enjoyed the Michael Chang comparison as he's practically the pioneer Asian American pro-athlete that attracted fans of all races.

http://jeremylinfanshq.com

Chad — April 23, 2012

Wow, you guys read waaaay too much into Lin being Asian-American! Ben Carrington would have you believe that racism kept Lin from being noticed before at Harvard or by NBA scouts. The reality is Lin played great his junior and senior years on a mediocre squad in a mediocre conference. He had a 17.8 average his junior year and 16.4 his senior year, in large part due to the many free throws he was able to take for his aggressiveness in driving the lane. He didn't get noticed much in the NBA at first for the same reason many rookies don't get noticed: they don't come from highly ranked college teams and haven't showed enough "wow" factor yet to warrant the attention. Lin came into national attention because of his outstanding contribution to the winning streak the Knicks had at the beginning of the year. It parallels Tim Tebow's sudden national attention. I'm not saying that Tebow didn't get attention already for his Heisman Trophy award, national championship with Florida, and his open Christian beliefs. Still, he got relatively ignored after being drafted by the Broncos until he put together last season's incredible winning streak. Winning contributed to both athletes' manias, not their ethnic backgrounds.

Gender Matters: Jeremy Lin and Asian American Masculinity | WMS 50 Intro to Gender Studies — July 23, 2014

[…] been shattered by Jeremy Lin. Jeremy Lin became the symbol of hope for Asian American men. Lin has broken racial barriers that no other Asian American men have done before. Lin has become a symbol of hope for me too because now I know that it is not impossible for Asian […]

Asian-Americans & Sports – YOUR DAILY SRIRACHA — May 16, 2016

[…] Suh, Stephen, and Kyle Green. “Linsanity and the Model Minority Myth.” The Society Pages. 17 Apr. 2012. Web. 24 Apr. 2016. <https://thesocietypages.org/roundtables/linsanity-and-the-model-minority-myth/>. […]