In our lifetimes, institutions like the International Criminal Court have fundamentally reshaped the sphere of international justice and accountability. Just a few decades ago, an international criminal indictment against a sitting head of state would have been much less likely or perhaps even inconceivable. Today, the President of Sudan is wanted by the International Criminal Court (ICC).

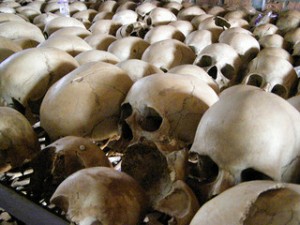

The ICC traces much of its legacy back to the Nuremberg Trials, which held dozens of leaders of Nazi Germany accountable for their actions after World War II. Since then, temporary international tribunals have been created to respond to specific situations of mass atrocity and human rights abuses, such as in Rwanda or the former Yugoslavia. Some of these tribunals are still in place today, but they have been joined by the ICC, the world’s first permanent, global court with jurisdiction over crimes seen as so egregious they are deemed crimes against all people.

We asked four leading experts to weigh in on some of the most controversial issues facing international criminal justice, including its potential interference with state sovereignty and its capacity to really curb human rights abuses.

Is the social control of crime at the international level a new development?

Naomi Roht-Arriaza: War crimes trials go back at least to the 14th century. Even the principle that some crimes are so heinous and so difficult for any one state to try has a long and storied pedigree, going back to cases involving piracy and slave trading.

Two things are perhaps new… One is a commitment by states, at least in terms of discourse, to combat the impunity of powerful actors, whether they be heads of state, militia leaders, or generals. This is where national criminal law has had difficulty in many states. It is why international tribunals or prosecutions are sometimes necessary. The new salience of fighting impunity is a change driven by civil society—human rights groups, journalists, family members of victims, lawyers, women’s groups, religious organizations, and others.

The second is the convergence of international criminal law with international humanitarian law (the law of war) and international human rights law. The kinds of crimes that international criminal law is predominantly concerned with—genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes, torture, enforced disappearance, piracy, slavery, and the like—are also almost all violations of the law of war when committed during armed conflict. And, in addition to individual criminal responsibility, they are violations of human rights for which states are responsible if they commit, condone, or fail to protect against them.

Susanne Karstedt: Moving control of mass atrocity crimes to the international level has been a long process with numerous setbacks… The Nuremberg Trials after World War II became a landmark of international criminal justice. Notwithstanding its numerous flaws, [Nuremberg] has become a benchmark for later trials, like Yugoslavia, Rwanda, and Cambodia. Regional initiatives and institutions [have also] had an undisputable impact, particularly in Europe and Latin America.

However, social control is comprised of more than formal institutions of criminal justice. It includes the reactions of communities towards crimes and offenders. Did social control in this sense move to the international level? Social control in the international sphere is highly dispersed among numerous institutions outside of the system of criminal justice, and [it is] based on regional and global power relations. A global civil society is emerging, with cosmopolitan actors and international NGOs actively working in the human rights regime and in crisis areas…

Kathryn Sikkink: One of the great paradoxes of criminal law in the past was that if an ordinary criminal killed one person, there was a strong chance that he would be prosecuted and sent to prison, but if a state leader ordered the murder of thousands, he would virtually never be held accountable. Thus, the expansion of criminal law to include state officials addresses a glaring inequality in the criminal law system. However, the great bulk of such accountability is happening in domestic courts, not in the international tribunals. [So] the key issue is not the emergence of international criminal law by itself. Rather, the big issue is the emergence of an interrelated but decentralized system of accountability for core human rights violations that includes international, foreign, and domestic prosecutions and courts. Many of these domestic prosecutions primarily use domestic criminal law, not international criminal law. But international criminal law and international tribunals have played a key back-up or supporting role in the process, both by producing some important legal innovations that have facilitated domestic trials and by making it more difficult for former state officials to escape accountability by going into exile.International law is sometimes seen as a direct contradiction to the carefully protected principle of state sovereignty, or the idea that states have control of their own affairs. How do you see this developing in the future?

Roht-Arriaza: Much of international law is, in fact, an embodiment of the principle of state sovereignty. States freely negotiate and choose to enter into treaties with other states. With some exceptions, they can choose not to comply with specific treaty provisions they disagree with, while still being part of the treaty. States, through their practice and behavior, create implicit rules that over time become accepted as customary international law—if states don’t like the emerging rule, they won’t be bound by it if they persistently object to it. There are a few exceptions: a handful of norms, such as a prohibition on genocide or crimes against humanity, are considered inherent to state-dom, and therefore cannot be changed via treaty or through persistent objection.

So, it’s not international law in itself that creates a challenge to state sovereignty. The international human rights regime does have a normative component, deriving from the inherent dignity of the individual, which says that people have rights whether their government chooses to recognize those rights or not. While we may disagree around the edges about what those rights are and how they are enforced, at the core there is little disagreement.Sikkink: States use their capacity as sovereign states to ratify human rights treaties that essentially “invite” other states and international organizations to intervene in issues that were previously considered internal affairs. This process is so far advanced that it begins to seem naïve for states to later complain that their sovereignty is being undermined. When I see states that have ratified multiple human rights treaties with detailed provisions for international supervision of human rights practices later complain about violations of sovereignty, I always think of the scene from the film Casablanca where the corrupt police inspector says that he is “shocked, shocked, to find that gambling is going on here” at the same time as he accepts the cash winnings for bets he has placed. In other words, states ratify treaties hoping to gain something, perhaps international legitimacy, and then later claim that they are “shocked” to find that the fine print of the treaty may actually be implemented.

Karstedt: State sovereignty is indeed crucial to the success and proliferation of international criminal justice. Nonetheless, with the establishment of international criminal tribunals, the international community has taken bold steps toward restraining sovereignty. In particular, the principles of the responsibility to protect and to prosecute restrict sovereignty and are often seen as direct and imminent threats to it. For example, as the international crime of genocide justifies (military) intervention… any definition of a situation as genocide can be seen as an invitation to intervene directly into sovereign states.Roht-Arriaza: It is also true that some states are more sovereign than others in practice: it is far easier to bring international criminal charges against a militia leader in the Congo than against Donald Rumsfeld. And international law can, and often is, used to enforce and expand the power of powerful states. This, it seems to me, is not a problem unique to international criminal law, but rather shows the limits of law itself when confronted with power.

The International Criminal Court is often hailed as the culmination of decades of work promoting international law and individual criminal accountability. Looking back on the ICC’s first 10 years, how do you assess its contributions and achievements?

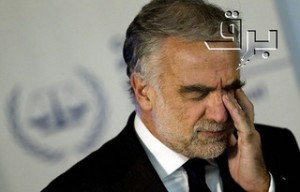

Wenona Rymond-Richmond: Decades of work promoting international law and individual criminal accountability culminated in the establishment of the ICC… Contributions and achievements of the Court include a warrant [for the arrest of] Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir: Charges filed by former Chief Prosecutor Luis Moreno-Ocampo against President Bashir include war crimes, crimes against humanity, genocide, rape, and mass murder as genocide. Of these charges, rape as genocide is the most groundbreaking. Prosecuting the crime of rape as genocide is unprecedented for the ICC and relies on two lesser-known ways of destroying a people, as stated in the Genocide Convention: “causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group” or “deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part.” Prosecuting President Bashir… will provide a legal precedence for the Court to pursue rape as a form of genocide in the future.

Additional contributions and achievements of the ICC include the conviction of Lubanga Dyilo [the first person convicted by the ICC, found guilty of conscripting child soldiers], the issuance of 22 warrants of arrest,

the overseeing of 16 cases in seven countries, and the investigation of 7 ongoing situations. Furthermore, the ICC has [created] an unprecedented series of rights for the victims to present their experience before the Court and established a trust fund to make financial reparations to victims. In this way, the ICC possesses an extraordinary opportunity to bridge the gap between retributive and restorative justice.

Karstedt: Defining the International Criminal court as the “culmination” of decades of development of international criminal justice seems to raise expectations to a very high level. Indeed, the ICC presently suffers from exaggerated expectations. I would suggest seeing the ICC as part of a process of continuous proliferation of legal instruments and institutions that deal with mass atrocity crimes and human rights violations. In the course of this process, numerous local, regional, and international institutions have emerged. Rather than being the apex of this build-up, the ICC should be seen as part of it, connected in various ways to local and regional forms of justice and peacemaking. Whether justice will cascade down from the ICC… as a model or whether [the Court] will be invigorated and changed by local initiatives, we do not know yet.Roht-Arriaza: The creation of the ICC was an enormous achievement, but it also created unrealistic expectations that the ICC—or any Court—could single-handedly do away with mass atrocity. There have been legitimate criticisms of the ICC: it is very slow, the Prosecutor has at times been willing to cut corners or has pursued too narrow a strategy…. The decision to focus on only African situations, while perhaps responding to… the constraints of the Rome Statute that limits who the ICC can investigate, has created frictions with African states. It has showed that the Achilles heel of the ICC, and of international justice in general, is the need to rely on state cooperation to actually detain suspects. Thus, when Sudan’s President Al-Bashir, wanted by the ICC, can still travel internationally and not be immediately arrested, the ICC’s long-term credibility is undermined, and, when the UN Security Council hears about the failure to cooperate and does nothing about it, the problem is compounded.

Sikkink: It is still very early… if we compare [the ICC] to other important regional human rights courts, like the European Court of Human Rights or the Inter-American Court of Human Rights, we see that [other courts] did relatively little in their first ten years. Both [of these] Courts have gone on to produce many landmark cases, but [not] in their first decades. The ICC has succeeded in setting itself up, surviving, and moving ahead with its tasks—far more than many predicted, given the initial harsh opposition from the United States. The initial prediction was that the United States would make sure the Court was never able to function properly. Instead, the United States, even during the Bush Administration, was obliged to change its position from active hostility to tacit acceptance.

Second, in order to evaluate the achievements of the Court, we don’t only want to assess what happens in The Hague, but the effectiveness of the whole “Rome Statute system.” The Rome Statute, which established the ICC, set forth the doctrine of complementarity, meaning that the ICC is a last resort when national courts have failed. …[O]ne important goal of the ICC is to work with states to modify their laws… and to develop their capacity to prosecute genocide, crimes against humanity, and war crimes in domestic courts. Thus, one underappreciated part of the work of the Court has been the degree to which it has spurred domestic legislative changes and prosecutions.

Some argue that international trials deter future human rights abuses. Do they? What are some other important effects of such trials?

Karstedt: As a criminologist, I am rather skeptical of criminal justice being a deterrent in general. First, even domestically, there is hardly any reliable evidence of a deterrent impact of criminal justice, neither on the individual offender, given the enormous recidivism rates, nor on the community, as high imprisonment rates do not seem to have a substantive impact on crime levels. Second, it is important to unpack the concept of deterrence: does this imply that perpetrators are deterred from re-offending or that non-offenders are deterred from committing a crime? As French sociologist Émile Durkheim pointed out, the function of punishment is not the prevention of crime, but the confirmation and validation of norms. Punishment thus enhances the solidarity of communities as their members rally around the visible demonstration and “monumental spectacle” of reactions to breaking rules, norms, and laws.

Indeed, the threat of prosecution may weigh little against what might appear to be gained in a conflict situation. Notwithstanding, the normative appeal of international criminal justice to “put an end to impunity” has emerged as a powerful tool. Both globally and regionally, mass atrocity crimes and human rights violations have subsided; it cannot be proven whether deterrence as threat of punishment or as normative change and confirmation of norms was actually decisive in this process. I would rather opt for the latter than for the former.

Roht-Arriaza: This is, empirically, very hard to prove—it’s the “dog that didn’t bark” problem. How do we know how many human rights abuses were deterred? We do have some anecdotal evidence that leaders of murderous regimes are afraid to be “sent to the Hague,” but that’s about it.

However, trials do serve other important purposes… they help stem revisionist history and establish facts, they allow victims and survivors to visualize the change in power that put the once all-powerful [on trial], and, sometimes, [they can let victims] confront [perpetrators]. Trials can, in this sense, rebalance power and head off vigilante justice and collective blame. They can also incapacitate, either through incarceration or political discrediting, local leaders who would otherwise continue to wield power, to terrorize, and to impede any change to a more just society. They can signal the emergence of norms of behavior, and help set the limits of the thinkable—and the unthinkable. And yet… trials are necessary but never sufficient.Sikkink: International trials are still too few and too recent to give any systematic judgment about their effects. …But some of my research shows that human rights prosecutions, including combinations of both international and domestic trials, are associated with improvements in human rights practices in transitional countries. This suggests that trials, including international trials, may indeed deter human rights abuses. …The most complex issue with determining the effects of international trials is that such trials are carried out in exactly those countries with the most severe situations, including conflict, authoritarianism, and chaos. This creates some selection effects…

Rymond-Richmond: I agree with fellow roundtable panelists that it is challenging to prove that international trials deter human rights abuse because far too few have occurred…. Yet, there are indications that legal interventions more broadly can deter future human rights abuses. [O]ne of the best and most creative examples is Savelsberg and King’s 2011 book American Memories. [These authors have done] a remarkable job of demonstrating that legal intervention may be a key mechanism in curtailing… mass atrocities. In addition, trials play an important role in shaping a nation’s collective memory of past atrocities and shaping present day laws against hate-motivated violence.

Citing the potential benefits, advocates claim trials are essential in the wake of human rights abuses. Others argue that resources would be better used for more far-reaching measures, like truth commissions or reparations. In the broader context of post-conflict rebuilding, what do you think is the role of criminal trials of individual perpetrators in dealing with widespread situations?

Sikkink: Why are transitional justice choices so often framed in either/or terms? It does not and should not have to be a choice among truth commissions, reparations, and trials. In fact, many countries use all three… Different transitional justice mechanisms serve different purposes. Until we know more about what works… I would not say that criminal trials are somehow [more or] less capable of addressing these situations than other mechanisms.

Karstedt: International trials are defining moments for societies emerging from a violent past. They symbolize the end to impunity for individual perpetrators and set the scene for further prosecution in years to come. For example, it was a common criticism of the Auschwitz trials that only a handful of perpetrators were brought to justice… However, [it] was a “cultural watershed” for German society, [F]or the first time, the voices of the victims could be heard.Roht-Arriaza: If all that is done is to try a few perpetrators, trials may be necessary but not sufficient to dealing with the aftermath of mass atrocity. What’s needed is a holistic effort to [re]construct social relations and political trust…. This may involve a wide array of measures, including truth-telling, documentation and archival work, reparations, revamping and cleansing of government services, memorialization, changes in educational curriculum, and more. Over the last few years, that agenda has broadened even more, so that we’re now including in the idea of “transitional justice” efforts to deal with the marginalization of groups…. While the needs will be similar, how each state does this will differ depending on their culture, traditions, the nature of the conflict, and so on. It will have to be done, moreover, with close attention to not reproducing earlier oppressions—of women, of indigenous peoples—and to ensuring that those most affected have a say.

International criminal justice has changed tremendously over the last several decades. Based on what we have seen, do you have any predictions (or hopes) about its future?

Sikkink: The main issue is not the future of international criminal justice, but the future of the interrelated but decentralized system of accountability for human rights violations (which includes international and domestic prosecutions). With regard to this system of accountability, the most striking theme in my book The Justice Cascade is the persistence of the demand for justice: I believe human rights prosecutions will not go away. Such prosecutions are not a panacea for all the ills of society, and they will inevitably disappoint as they fall short of our ideals. They represent an advance, however, over the complete lack of accountability of the past, and they have the potential to prevent human rights violations in the future.

Roht-Arriaza: Our expectations of international criminal justice will eventually come more into line with what it can actually accomplish. It can’t put societies back together, it can’t bring closure to those who have suffered horrible losses, and it can’t rid the world of international crime, any more than domestic courts have been able to abolish ordinary crimes. It can make modest contributions to each of these things, and that’s all to the good. I think we will see new ways of intertwining international and national prosecutions, supporting the national courts, [and] linking reparations and structural reform to justice efforts. And I think that we will see new kinds of conflicts over natural resources and land, which will require their own set of holistic responses.Rymond-Richmond: My hopes … include continued and increased global support of the International Criminal Court. The ICC has the potential to contribute to world peace and security. However, international criminal justice is only one piece of [the] holistic approach necessary to eliminate human rights violations. [This] includes identifying precursors to mass atrocities, increased international and national prosecutions, assistance and protection for refugees and internally displaced people, raising the status of women, eliminating racial and ethnic discrimination, understanding the context of genocide, and [funding] reparations for victims.

…We must try, though a variety of means, including scholarship, activism, and legal interventions, to end the massive killing, raping, and displacement that has left a scar on the twentieth century and each century before. What is the alternative? For individuals, states, or the international community to be bystanders to atrocities is shameful and the implications of inactivity are deadly. Advancements in international criminal justice are a step in the right direction.

Karstedt: The development and proliferation of international criminal justice testifies to the human capability of inventing institutions—good ones as well as bad ones that do a lot of harm. …Its history also testifies to the many obstacles and setbacks that international criminal justice has to confront. It is my hope that international criminal justice becomes the beacon for institutions all over the world to end impunity for human rights violations and mass atrocities, and that it promotes the empowerment of citizens to find their own ways out of conflicts and violence.

Comments 7

Chuck Turchick — February 20, 2013

Professor Sikkink said, "...the United States, even during the Bush Administration, was obliged to change its position from active hostility to tacit acceptance."

Coincidentally, the day before this Roundtable was posted, U.N. Ambadassador Susan Rice made a statement to the Security Council on protecting civilians in armed conflict(http://usun.state.gov/briefing/statements/204513.htm).

Toward the end of that statement, she said: "Mr. President, we fully support the Secretary-General’s call for this Council to be more active in addressing violations of international law and to strengthen accountability. The United States strongly rejects impunity and supports efforts to hold accountable violators of international humanitarian and human rights law. Our longstanding support of international tribunals and efforts to document ongoing atrocities in such places as Syria reflect this commitment. Recent events, including the conviction of Charles Taylor by the Special Court for Sierra Leone and the International Criminal Court’s judgment against Thomas Lubanga Dyilo of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, show us that accountability for those who commit atrocities and justice for their victims is possible. Yet, too many perpetrators remain free. This Council needs the facts and strong reporting to help bring to justice the perpetrators of crimes against civilians."

So maybe the U.S. has moved beyond "tacit acceptance" of the ICC. Oh, except for U.S. perpetrators, of course.

exteme.info » Sudan — October 31, 2013

[…] Featured here- thesocietypages.org/roundtables/international-criminal-ju… […]

Friday Roundup: Awards Edition! » The Editors' Desk — December 21, 2013

[…] “International Criminal Justice, with Susanne Karstedt, Wenona Reymond-Richmond, Naomi Roht-Arriaza, and Kathryn Sikkink,” by Shannon Golden and Hollie Nyseth Brehm. […]

Friday Roundup: February 15, 2013 » The Editors' Desk — April 1, 2014

[…] “International Criminal Justice, with Suzanne Karstedt, Naomi Roht-Arriaza, Wenona Rymond-Richmond, a…,” by Shannon Golden and Hollie Nyseth Brehm. In which we consider states, sovereignty, and efforts to assert international justice with four experts. […]

Macs for Kid's » Blog Archive » Sudan — September 6, 2014

[…] Featured here- thesocietypages.org/roundtables/international-criminal-ju… […]

Give an example of an international justice system. How do the various international justice systems cooperate and coordinate in combating global crime? What would happen if the communication among these international justice systems broke down, or was no — January 14, 2017

[…] Shannon G., Hollie B. (2013). TheSocietyPages.org. Retrieved from https://thesocietypages.org/roundtables/international-criminal-justice/ […]

Give an example of an international justice system. How do the various international justice systems cooperate and coordinate in combating global crime? — January 16, 2017

[…] Shannon G., Hollie B. (2013). TheSocietyPages.org. Retrieved from https://thesocietypages.org/roundtables/international-criminal-justice/ […]