In 2012, the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS) removed a record high of 419,000 people—ten times as many as in 1991, and more than during the entire decade of the 1980s. This increase can be attributed to the fact that immigration law enforcement in the United States has never been fully separated from criminal law enforcement. The term “crimmigration,” coined by law professor Juliet Stumpf, reflects the intersection of these two systems; a convergence of policies has deepened their entanglement. Almost 200,000 of the 2012 deportations were the result of a criminal conviction. Below, we ask a panel of experts to elaborate on “crimmigration”—both as a phenomenon and a field of study—and its possible repercussions for migrants and U.S. immigration law.

What do people mean when they say “crimmigration”?

Ryan King: …The connection between crime and immigrants has a lengthy history. Peruse the pages of the American Journal of Sociology in the first quarter of the 20th century and you find a lot on this topic. The commentary …was sometimes pretty nasty (for example, Edwin Grant’s “Scum of the Melting Pot” in 1925). But “crimmigration” seems to capture the contemporary zeitgeist; the more recent wave of laws and opinions—both scholarly and public—on immigration and crime.

Tanya Golash-Boza: Crimmigration is the merging of criminal and immigration law enforcement—two different regimes of law. Criminal law enforcement is related to violations of the criminal code and requires a series of protections including the prohibition of unreasonable search and seizure, the right to appointed counsel, and the right to a trial by jury. Immigration law enforcement is related to violations of the Immigration and Nationality Act and does not include these same protections.

A person who violates the criminal code faces arrest and incarceration. A person who violates provisions of the Immigration and Nationality Act by, for example, overstaying their visa, entering the United States without inspection, or ignoring a deportation order, faces arrest, detention and deportation. The United States considers neither detention nor deportation punishment, so these procedures do not require due process protections…The merging of criminal and immigration law enforcement has not led to the provision of due process protections to immigration law enforcement. Instead, it means that the distinction between the two law enforcement regimes has been blurred. There are three primary ways we have seen this convergence: 1) Non-citizens convicted of crimes can be subject to deportation; 2) Police officers can be deputized to enforce immigration laws; and 3) Jails and prisons hold non-citizens until immigration law enforcement agents arrive to determine their immigration status.

Yolanda Vázquez: “Crimmigration” should not be defined as simply the “criminalization of immigration law.” In fact, incorporating the role that immigration law and its enforcement play in the criminal justice system still fails to truly describe “crimmigration”…[it]must be defined as a portmanteau, an institutional structure in which criminal and immigration law have merged in various ways to create a singular and distinct concept with its own structure of laws, procedures, and practices.

What are some key turning points in crimmigration in terms of punishment including deportation?

RK: 1986. The Immigration Reform and Control Act …was a game changer for two reasons. First, it enabled the Alien Criminal Apprehension Program that had a direct effect on deportations. Second, this law, in tandem with the 1986 Anti-Drug Abuse Act, represented a turning point in how we deal with problems related to crime. …American penal philosophy fully embraced incapacitation, deportation, and limited judicial discretion. These would be hallmark features of American criminal justice for the next two or three decades. It’s no coincidence that the number of criminal deportations increased dramatically after 1986.

YV: While many attribute the various Congressional Acts which began in 1986 to be the beginning of “crimmigration,” the foundational blocks of “crimmigration” actually began much earlier. …The 1960s and 1970s were monumental in shaping the structure of “crimmigration” as we currently see it.

…In 1964, the Bracero program was eliminated. The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 (“The Act”) abolished the national origins quota [and] established a quota on the Western Hemisphere countries [and restricted] unskilled migrant labor. Further quota restrictions were put in place with the Immigration and Nationality Act Amendments of 1976. While these may have had a positive affect for some nations …[t]hese laws negatively affected legal immigration …from Mexico…. The changes to criminal law during that time also contributed to the structuring of “crimmigration.” The War on Crime and The War on Drugs shifted societal attitudes towards those who were poor, addicted to drugs, or labeled a “criminal.” During this time, the focus on the eradication of crime, drug, and poverty shifted [the U.S.] from a social welfare state to a penal welfare state. …Society now believed individuals …were the cause of social problems instead of the victim. They were lazy and morally depraved. Punishment was the only remedy.By the 1980s. …[m]ore immigrants were coming from non-European countries. [Those] entering illegally were no longer from Southern Europe, but from Mexico and poor. …seen as the cause of social ills…

Looking at it through this history, it [is] easy to see why the Congressional Acts of the 1980s and 1990s focused on the punishment and removal of immigrants, either specifically or through other Legislative Acts directed at combating crime.

While Vázquez and King emphasize the institutionalization of “crimmigration” from the ‘60s to the ‘80s, Golash-Boza reflects on changes since the 1996 immigration reform.

TGB: There are two key turning points in crimmigration: the passage of the 1996 laws and the creation of the Department of Homeland Security (DHS).

[First], Congress passed two laws that fundamentally changed the rights of all foreign-born people in the United States: the Anti-Terrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act and the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act of 1996. These laws were striking in that they eliminated judicial review of some deportation orders, required mandatory detention for many noncitizens, and criminalized illegal entry and re-entry. [They] transform[ed] some immigration violations into crimes.…The 1996 laws took away most of the judge’s discretionary power in aggravated felony cases. [Those convicted now] face mandatory and automatic deportation, no matter the extenuating circumstances. …[Even] legal permanent residents who have lived in the United States for decades, have contributed greatly to society, and have extensive family ties in the country, are subject to deportation for relatively minor crimes they may have committed years ago.

In 2003, in the aftermath of the September 11th terrorist attacks, the DHS was created and immigration law enforcement became one of its central missions. [This] meant a massive infusion of funds …[and] facilitated more aggressive enforcement of the 1996 laws.

Golash-Boza explains how the laws didn’t necessarily change, but their funding and enforcement ramped up considerably under the DHS.

TGB: …Congress has appropriated increasing amounts of money for immigration law enforcement, in line with DHS’s annual budget requests. The FY 2011 budget for DHS was $56 billion, 30% of which was directed at immigration law enforcement through Immigration and Customs Enforcement and the Customs and Border Patrol. Another 18% …went to the U.S. Coast Guard and 5% to U.S. Citizenship & Immigration Services. [O]ver half of the DHS budget was directed at border security and immigration law enforcement.

To put [DHS’s] $56 billion in perspective, [in 2011] the Department of Education budget was $77.8 billion and the Department of Justice’s was $29.2 billion.

The rise in deportations over the past decade primarily stems from Executive Branch decisions to expand immigration law enforcement, as part of the broader project of the War on Terror.

Who is most likely to be the target of crimmigration practices?

RK: Race, sex, and class matter [for non-citizens] in much the same way that they matter for the punishment of citizens. For instance, research shows that being Hispanic and a non-citizen [separately and together] increases your chance of incarceration in the federal courts. In addition… it seems pretty clear that the current discourse on crime and immigrants is very much about those from Central and South America. When Representative Steve King states “for every… valedictorian there is another hundred out there that they weigh 130 pounds and they’ve got calves the size of cantaloupes because they are hauling 75 pounds of marijuana across the desert,” he doesn’t exactly conjure up an image of a European immigrant. The face of the debate has a dark complexion and a Spanish accent.

What’s really unfortunate is how far apart the public debate and the scholarly research are. [Research] suggests immigrants are not more crime prone, but I have my doubts about whether even the best of research will change many opinions on this topic.

TGB: The disparities in deportations by race and gender are staggering. More than 97% of people deported last year were Caribbean or Latin American immigrants, even though they only account for 60% of non-citizens. And over 90% were men… Deportation is happening at unprecedented rates, with almost no due process, and it is primarily targeted at black and Latino men.

I have not seen representative data on the class status of deportees. However, I interviewed 150 deportees in four countries and the overwhelming majority …seemed to be working-class or poor. Middle-class people are less likely …to be arrested for [the] minor offenses [that] make up the vast majority of crimmigration arrests.

…So long as police cooperate with immigration law enforcement agents, we can expect for the race and gender profiling common in criminal law enforcement to have spillover effects into immigration law enforcement.

Vázquez agrees:

YV:The “criminal alien” is the poor, young, male, Latino. …As I discussed above, the immigration laws put into place during the 1960s and 1970s greatly affected the legal migration of Mexicans and Central Americans …as well as the race and ethnicity of future immigrants into the United States. In addition, the enforcement of immigration law …is mostly seen in states and localities with increasing numbers of Latinos. …The War on Crime, the War on Drugs, racial profiling, and federal prosecution …have all disproportionately impacted who is labeled a “criminal alien.”

While the implications are overwhelming, our participants shared their thoughts on the most profound social effects of “crimmigration” law and enforcement. Golash-Boza sees a reasonable distrust of the police.

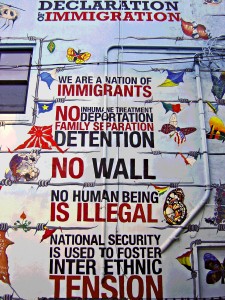

TGB: Unfortunately, Section 287 (g) of the Immigration and Nationality Act, which allows local law enforcement officers to perform immigration law enforcement functions, is being adopted in communities across the country. …In theory, inter-agency collaboration could enhance national security. In practice, the adoption of 287 (g) decreases local-level security.

[Since] 287 (g) gives police officers the authority to call immigration agents to find out if any person they encounter is undocumented …people who are undocumented or whose loved ones are undocumented will be less likely to call the police to report crimes, even when they are the victims. [It] could even lead to people being scared to take their children to the hospital.Although the 287 (g) program deports few women, [it has other] pernicious effects on women… [when] men get arrested, women and children get left behind. …A recent study [also] found that only about half of all battered women report perpetrators to authorities. Immigrant women with stable status report at a rate of 43%, [but] undocumented women at a rate of [just] 19%…. women have good reason to fear deportation [their own or their partner’s] when the police cooperate with ICE.

Nearly one-quarter of those deported in 2013 were also parents of U.S. citizens. King and Vázquez worry about the effects of crimmigration enforcement on those children and families, as well as the communities in which they live.

RK: …Human Rights Watch reports that 1.6 million U.S. residents are now separated from a spouse or child because of criminal deportation. I don’t have great confidence in that precise number, but even if that estimate overshoots by a million, we are still left with a very large number. I’m curious to see if this issue… receives much political attention, because it could put many politicians in a bind, namely those who preach about the importance of family…. When it comes to deportation you can’t always have it both ways.

YV: Families are torn apart …left without a means of financial, physical, and emotional support. Children are left with one or neither parent …Communities across the United States are destabilized and fractured.

[Other] nations are [also] feeling the weight of returning individuals from the United States and the drying up of remittances that supported their economic growth and the personal livelihoods of their citizens. As a result, they remain unable to prosper or compete politically [and economically]…

[Third], these actions create, maintain, and promote conditions that influence the social, cultural, economic and political structures in the United States. …[I]mmigration’s “management” of non-citizens is absorbed into the structures of the criminal system and subjected to its consequences: the labeling as a “criminal,” the stigma of “other,” the justification for “punishment,” and the bars to employment, housing, education, and voting. “Crimmigration” reifies marginalization….

In the face of these stark realities, our contributors shared some practical, if large-scale, solutions for addressing the harmful effects of “crimmigration.”

RK: …I first want to acknowledge and encourage others to be upfront about how messy and difficult immigration law inherently is. It often forces choices between competing principles.…I’d aim for reinstating judicial discretion, specifically the JRAD (judicial recommendation against deportation). This power …was curtailed in 1990. ….Now I’m not naïve; with discretion comes the potential for discrimination. But my guess is that many judges would allow for sanctions other than deportation in many cases, especially when it means breaking up a family.

TGB: The rights to due process and a fair trial are fundamental …in the United States, yet these procedural protections are denied to non-citizens in deportation proceedings. At a minimum, people facing deportation should have the same protections as those facing incarceration. People facing deportation should have the right to appointed counsel, immigration judges should [have discretion], immigrants awaiting their hearings or deportations should have bond hearings….

Further, the police should not be involved in enforcing immigration laws. [That function] places [officers] at odds with their mission to enforce the criminal code and enhance public safety.

YV: First, there needs to be a complete severing of the relationship between the civil immigration and criminal justice system. …[T]he Acts [from] the ‘80s and ‘90s should be abolished …[so] the immigration system [can] focus on the removal of those truly a danger to the community and nation. Judicial discretion would be reinstated…. Operation Streamline could be dismantled. Immigration violations could be taken out of the criminal system and heard in immigration court …[but with appointed] counsel …since their liberty, property, etc. are at risk; the law is complicated, and the opposing side is represented by counsel. Immigration [shifted to] purely outside of the criminal justice system would allow law enforcement and its limited resources to focus on the investigation, detention, and arrest of dangerous and violent individuals [rather than on checking documentation statuses]. It would also lower the rate of racial profiling and [strengthen] the relationship between immigrants and law enforcement….

Finally, we need to restructure immigration law in a manner that acknowledges the structural inequalities that cause unauthorized migration and disparate treatment of immigrants from certain nations. …By severing the ties between immigration and criminal law and changing the rhetoric to focus on the contributions immigrants, including unskilled workers, make, we can begin to work toward true comprehensive immigration reform.

Comments 7

Friday Roundup: February 28, 2014 » The Editors' Desk — February 28, 2014

[…] “Crimmigration”: A Roundtable with Tanya Golash-Boza, Ryan King, and Yolanda Vàsquez, by Suzy McElrath, Rahsaan Mahadeo, and Stephen Suh. What happens when criminal and immigration enforcement come together? […]

Penny — March 1, 2014

A roundtable would be more informative and stimulating if all the participants were not in total agreement with one another.

chris — March 5, 2014

I don't see complete consensus here, but it tells us something when researchers as varied as Professors Golash-Boza, King, and Vázquez seem to identify the problems and potential solutions in similar ways. Some phenomena cry out for this sort of careful analysis even when a rough consensus exists among academic experts. For example, Jeff Manza and I initially had a tough time finding credible scholarly "debates" regarding ex-felon disenfranchisement, but points of disagreement emerged as more was written on the phenomenon. I'm guessing this will be the case with crimmigration (and climate change, and mass incarceration, and...) as well.

Crimmigration | RETURN MIGRANTS/DEPORTEES — February 16, 2015

[…] http://thesocietypages.org/roundtables/crimmigration/ […]

Race and Border Control: Is There a Relationship? — April 6, 2015

[…] has transformed the immigration and criminal justice systems, forming ‘crimmigration,’ a distinct system that has its own structure of laws, policies, and practices, formed through the various ways that […]

Race and Border Control: Is There a Relationship? » Antropologia Masterra — April 9, 2015

[…] has transformed the immigration and criminal justice systems, forming ‘crimmigration,’ a distinct system that has its own structure of laws, policies, and practices, formed through the various ways that […]