The old cliché says that beauty is in the eye of the beholder. But who is the beholder? That’s complicated when we look through the unique lenses of different countries and societies. In a more globalized world, culture, race, media, and power intersect to create an idea of “beauty” admired by a collective, rather than an individual.

In my daily browsing of Reddit, the popular online news, humor, and information aggregation site, I did a double-take when I saw a submission titled, “Korea’s Plastic Surgery Mayhem is Finally Converging on the Same Face: Miss Korea 2013 Contestants.” The picture shows 21 pageant contestants later found to be competing in a regional, not national, contest. Still, the women’s hairstyle and dress differ, but that’s about all. Whether it’s the effect of popular plastic surgery or the pageant using a single person to Photoshop the headshots—or, more likely, both—these women look virtually the same.

To think through this startling homogeneity, a sociologist has to ask why “beauty” would come to mean just one thing in one culture. What does the Korean convergence mean about the racial, ethnic, and cultural aspects of physical beauty around the world? Answering such big questions means looking at the political and gendered context of women’s bodies, the historical ideals of beauty and their differences and similarities across countries and societies, how certain beliefs of physical image intersect with cultural stereotypes about Asian Americans, and, finally, how ideals of physical beauty are evolving.

Beauty Pageants and the Male Gaze

Whenever we discuss issues and ideals related to physical beauty and women’s bodies, we need to be conscious of the “male gaze.” In basic terms, the concept refers to heterosexual men objectifying women and judging their value almost entirely on physical characteristics. The male gaze involves seeing women solely as erotic images, two-dimensional tools for the visual pleasure of heterosexual men rather than human beings with a comprehensive set of thoughts, emotions, and agency. It is within this context that many women and men criticize the existence of beauty pageants altogether: they are often premised on, and result in, the objectification of women, while also reinforcing gender roles and male supremacy.

Just as important, beauty pageants around the world can also result in the homogenization of women. These visual displays are often framed around a set of predetermined norms or prevailing opinions about what heterosexual men consider attractive or erotic. Often, these predominant attributes are very narrowly focused and defined, leaving little room for variations or exceptions. Today, in many countries including the U.S., the general beauty standard for women includes physical characteristics such as a triangular-shaped face, small nose, high cheekbones, long legs, small waist, moderately sized breasts, curvaceous thighs, and a “proper” proportion among the latter three (that is, a less exaggerated form of the hourglass figure lauded in earlier decades). This is not to say that many men and women do not appreciate and covet different physical standards, only that this is the dominant cultural standard. Those with preferences for, say, bodies with three limbs rather than four, narrow hips, or broader measurements in any portion of the body are considered outside the norm—even, to the extreme, “fetishists.”

Taken together, the male gaze in general and beauty pageants in particular set the stage for modern societies to equate physical appearance and a specific attractiveness with value judgments of superior versus inferior, normal versus abnormal, and good versus bad (or even evil). In our particular discussion of the Miss Korea 2013 contestants, these cultural elements intersect with the historical and political dynamics of race and ethnicity.

What Constitutes Physical and Cultural Beauty?

Beauty ideals are sure to be distinct among different racial and nationality groups. Looking at the portraits of the Miss Daegu contestants brings up the question of whether Asians and Asian Americans are implicitly or explicitly conforming to dominant, white, western standards of physical beauty. Let’s start with the meaning of light skin tone and regional beauty standards. As historians and other scholars have pointed out, European colonization of non-white countries in Africa, Asia, and Central/South America elevated European history and culture, including the physical appearance of whites as a racial group. This solidified Europeans’ position at the top of the political, economic, cultural, and military hierarchy on a global scale. As their culture spread, frequently by means of physical conquest, racially-based standards of beauty came to include light-colored hair and eyes and, perhaps most importantly, light skin. After the U.S. rose to the top of the global hierarchy in the 20th century, these European-based images of beauty eventually melded into a general white-based standard of beauty.

Meanwhile, the cultural dynamics and connotations of light skin operate slightly differently within Asian societies. To a certain degree, white images of beauty have been diffused within Asian countries. However, in many Asian societies, the high status associated with light skin has less to do with emulating whites as a racial group than with representing wealth and privilege. Upper class people would not need to perform manual labor. Being able to hire others to do work in the hot sun left the wealthy indoors in the shade—cultivating a distinct difference between the fair skin of the upper classes and the sun-baked visages of laborers.The introduction and spread of capitalism and western culture in the last several decades has added another layer of cultural meaning to light skin in Asian societies. Now it is associated with whites as a racial group and the corresponding aura of global wealth, power, and status. In other words, as U.S. political, economic, and cultural influence became widespread after World War II and intensified with the emergence of globalization starting in the 1980s, U.S. political leaders, celebrities, lifestyles, media products, material goods, and appearances became the standards aspired to among many throughout Asia.

Recent observations by mainstream media outlets, bloggers, and social media sites confirm that the preference for light skin is alive and well in many Asian countries. Skin-lightening creams and lotions are as mainstream as lipstick and mascara. Further, plastic and cosmetic surgery and procedures such as breast augmentations, rhinoplasty (nose jobs), collagen lip implants, and blepharoplasty (an eyelid surgery meant to give Asians a more European “double-eyelid” appearance) are commonplace. For example, data from the International Society of Aesthetic Plastic Surgery show that, in 2011, four of the top eight countries in terms of total cosmetic procedures performed were in Asia: China #3, Japan #4, South Korea #7, and India #8.

Multi-morph composites of the 2005 Miss Universe delegates. Click the image for the artist’s description.

Within the Asian American community, the beauty debate has centered on the cultural implications changing physical appearance and whether it represents a wholesale conforming to white standards of beauty. People ask, “Where—and what—is Asian beauty?” This question is highlighted in a recent segment from ABC’s NightLine about an increase in Asian supermodels. They are apparently becoming more prevalent on U.S. and international runways, but the fashion industry may have, rather than reify a diverse beauty, simply reinforced racial stereotypes about Asians, such that all Asians look the same.

Of course, there are many perspectives on whether particular cosmetic procedures represent an adherence to western standards of beauty or an emergent Asian standard. There is, however, some agreement that white ideals dominate media and fashion industries in industrialized nations and influence on how young Asian and Asian American women judge themselves and their physical appearance. Within the U.S., Asian Americans are a visible racial minority group, and particularly young people and those who live outside Asian-majority enclaves and cities, feel palpable pressure to “blend in,” to avoid being seen as physically or culturally different. Just look to sitcoms: Asian women are presented as largely homogenous, either sexualized or subservient. The more “Asian” a character appears physically, the more you can expect a stereotypical and demeaning portrayal of asexual nerdiness.

Collectively, these pressures can exert stress and take a negative emotional toll on Asian Americans. They can be disastrous for Asian American women in particular. For example, data from the American Psychological Association and the National Alliance on Mental Health point out that U.S.-born Asian American women between ages 15-24 have higher rates of depressive symptoms, suicidal thoughts, and suicide attempts than the national average, including White women. Further, pioneering research from Christine C. Iijima Hall published in 1995 and since confirmed by studies published in academic journals such as Eating Disorders, The International Journal of Eating Disorders, and The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease describe how young Asian American are also particularly vulnerable to eating disorders, much of it influenced by pressures to conform to the model minority and idealized beauty images.

Physical Homogeneity and the Yellow Peril

This question of what constitutes physical beauty among Asians and Asian Americans brings up some further implications. The first, mentioned by several commenters on the Reddit post that got me thinking about just why the Miss Daegu contestants all looked so eerily similar, is that the adherence to one physical standard seems to reinforce the unfortunate stereotype that all Asians look the same. Sure, there tends to be a certain degree of visual conformity and homogeneity in beauty pageants in general. But, as many Asian Americans can attest, the stereotype that all Asians “look the same” feeds into an older, more nefarious idea: that we are “The Yellow Peril.” In this historical yet lingering spectre, Asians are faceless, an almost sub-human mass bent on attacking, taking over, and/or destroying U.S. and/or western society, economy, and culture.

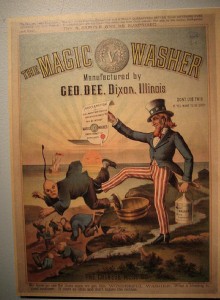

Take, for instance, the magazine advertisement for soap (that’s what Uncle Sam is holding in his left hand) shown below. It comes from the 1800s. The image’s main focus is Uncle Sam kicking the Chinese out of the country—sending them “back” toward the squinty-eyed sun in the horizon. The physically indistinguishable Chinese scurrying into the background represent the Yellow Peril vanquished by American might, individualism, and superiority. The fact that the Yellow Peril is being vanquished by soap not-so-subtly reinforces the idea that Asians are a dirty scourge, all alike, all undesirable. The massing of Asians into one homogenous group can seem laughable in a vintage ad, but it has led to many tragic instances of blatant bigotry, discrimination, and even violence.

via SocImages

In 1982, the U.S.—and the world—saw a graphic enactment of the stereotype that all Asians are the same. Vincent Chin, a naturalized U.S. citizen, was murdered in Detroit, MI. The country’s economy was in a recession, and its auto industry, based in Detroit, had been particularly hard-hit. Many Americans accused Japanese automakers such as Toyota, Honda, and Nissan of using unfair trade practices to gain market share in the U.S. As they lost jobs, as factories closed, these white Americans resented Japanese success. The Yellow Peril seemed poised to “take over” the U.S., starting with its auto industry.

Back to Chin. One night, he was out with friends in a Detroit bar, celebrating his upcoming wedding. Two white, auto workers, Ronald Ebens, and Michael Nitz, assumed Chin was Japanese, and they began taunting him, accusing him of stealing their friends’ jobs. A fight erupted and spilled into the street. Ebens and Nitz chased Chin for blocks before cornering him. They beat Chin to death with a baseball bat. For the murder, Ebens and Nitz received only three years of probation and $3700 in court fees. Public outrage over the lenient sentences eventually persuaded the federal government to try the two men for violating Chin’s civil rights. However, after the case was moved to the predominantly white, working class city of Cincinnati, OH, an all-white jury acquitted both men of all charges. The outrage proved impotent.

In this context, when Ebens and Nitz saw Chin, they saw an embodiment of the Yellow Peril. Asians were non-human, a faceless, collective threat that, for one moment, could be confronted, could be stopped. So, beyond the “weirdness” of the 2013 Miss Korea contestants looking physically similar, historical and cultural contexts frame the pictures as downright dangerous: they reinforce the idea that Asians are identical, a homogenous group with no individual members. That’s clearly a dangerous idea.

The Ironies of Multiculturalism

Ironically, globalization, multiculturalism, and increased racial/ethnic diversity in U.S. society have both propagated generic standards and pressured societies to be more open and celebratory of more diverse forms of cultural representation. Two recent pageants in the U.S. offer hopeful indicators of a move away from white-centric notions of beauty: Lebanese American Rima Fakih as Miss USA 2010 and Indian American Nina Davuluri as Miss America 2013. Notably, both are readily identifiable as women of color and have noticeably darker skin tones than their white pageant counterparts. Their wins were significant symbolic steps for quintessential American brands, visible reminders of the country’s “melting pot” ideal.

But is one thing for an individual Asian American woman to win a prestigious beauty pageant and another for Asian Americans as a group to be treated equally and justly as “real” Americans. Just as newsworthy as Ms. Fakih and Davuluri’s crownings was the racist backlash on social media, complete with declarations that each woman was not an American, a terrorist, and an insult to (white) American society.

Still, the U.S. may actually be at the forefront of promoting more diverse images of beauty. As the Census Bureau has long predicted, by 2045 or so, non-Hispanic whites will become a minority (they will still be the largest racial group by far, but they will comprise less than 50% of the U.S. population compared to groups of color). This has already happened in a few states such as California, Texas, and New Mexico. These demographic changes are slowly leading to cultural changes, as people of color are increasingly integrated within U.S. institutions such as politics, business, education, and media and entertainment. We’ve already seen the popularity of artists and celebrities of color from Chuck Berry to the Jackson Five, Jay-Z, and Oprah Winfrey. Now we’re seeing the Asian and Asian American population slowly accepted as cultural mainstays: hip-hop group Far East Movement has a 2011 chart-topping hit “Like a G6,” Psy and his “Gangnam Style” video were ubiquitous in 2012, and K-Pop is a fast-growing genre in the U.S., highlighted by Girls’ Generation winning YouTube’s 2013 “Video of the Year” award for their video “I Got a Boy.” The advertising industry has made notable strides in including more actors of color in their advertisements and promotional material on television, print, and billboards. No longer are the Asians being chased away in the soap ads; now they’re shown driving kids to soccer practice in American-made SUVs.The spillover effect is that, while there’s a huge amount of work left to be done (particularly on television), Americans from all backgrounds are becoming more open to a more diverse set of images of physical beauty. Asian societies, however, seem to be lagging behind the U.S. in terms of their mainstream representations of physical beauty. Visual homogeneity is the norm. Part of this is due to the general racial homogeneity of Asian countries as compared to the U.S. But beyond demographics, prevailing cultural norms within many Asian countries still seem to favor facial and bodily uniformity.

If the U.S. is, indeed, at the forefront of presenting a more “democratic” view of physical and cultural beauty, Asian countries must play catch-up. Sure, like most people, I can agree that the young women who competed in the Miss Daegu (and later, the Miss Korea) pageant are attractive. They’re pageant contestants; it’s kind of the job. Nonetheless, like most people, I see a lot of different kinds of attractive in the world. Beauty can wear more than one face—when millions of beholders make it known.

Recommended Reading

Shilpa Davé, LeiLani Nishime, and Tasha Oren (eds). 2005. East Main Street: Asian American Popular Culture. New York: New York University Press.

These essays describe numerous Asian American cultural practices including their historical meanings and sometimes contested place within mainstream U.S. society.

Youna Kim (ed). 2014. The Korean Wave: Korean Media Go Global. New York: Routledge.

This anthology takes an in-depth, critical look at the global explosion of “K-Pop.”

Kent Ono and Vincent Pham. 2008. Asian Americans and the Media. New York: Polity.

A comprehensive survey of how Asian Americans have been portrayed in various U.S. media and emerging forms of Asian American self-expression.

Sheridan Prasso. 2006. The Asian Mystique: Dragon Ladies, Geisha Girls, and Our Fantasies of the Exotic Orient. New York Public Affairs Publishing. By describing the lives of numerous Asian women, this book explores the context of ever-present and hypersexualized stereotypes.

John Tchen, Kuo Wei, and Dylan Yeats. 2014. Yellow Peril! An Archive of Anti-Asian Fear. Brooklyn, NY: Verso. Details the “yellow peril” phenomenon from the Enlightenment through the 2012 U.S. elections and beyond.

Comments 16

Han — June 7, 2014

"However, in many Asian societies, the high status associated with light skin has less to do with emulating whites as a racial group than with representing wealth and privilege."

Is that true ^?

Talking with several people from Asia, they told me that American Whites were worshiped and socially popular for being White. They told me it is not representing wealth and privilege, but representing what society deems is cool. Wealth and privilege does not equal socially liked or popular.

Lovely Links: 6/20/14 - Already Pretty | Where style meets body image — June 20, 2014

[…] Watching Korean culture converge on a single ideal of beauty, Professor C.N. Le shows a process at work around the world. Sobering. […]

The Asian Standard of Beauty? | Take Two — October 10, 2014

[…] http://thesocietypages.org/papers/homoegenization-of-asian-beauty/ […]

Ash — December 16, 2014

It is simply ignorant to think that East Asian people are trying to "be Caucasian" just because they prefer pale skin and big eyes. Caucasian (especially American) people should stop thinking that they are the center of the world and that everyone is trying to copy them or feel as if they are on a pedestal to be worshipped.

FYI, the ideal standard for Asian beauty was created long before our Asian ancestors even knew of the existence of Caucasian people or had contact with Western culture.

Besides, the ideal Asian beauty is almost a complete opposite of what Caucasian people look like.

The preference for fairness of skin is due to paleness being seen as youthful, innocent and pure, and the skin should not be ghostly white, but more of a peachy-beige, milky look. Do not say that Asian people are trying to have Caucasian skin, because Caucasian people do not even like having pale skin anyway. Nowadays they are all so dark and tan that one might as well say that Caucasians are trying to look Black or Indian.

The same is true for the preference for big eyes, because big eyes represent youth, innocence and purity, and these traits are more valued in Asian women than other traits. Not because Asian people want to have Caucasian eyes.

Besides preference for paleness of skin and bigger eyes, the Asian makeup styles and ideal facial features are also opposite of the Caucasian standard.

In general, Caucasian (especially Western cultures) standard of beauty seeks a mature, seductive and sexy, sultry look, whereas Asian (specifically East and some Southeast Asian cultures like Thailand and Vietnam) standard of beauty seeks a youthful, pure, innocent and cute look.

Examples are- Caucasians prefer arched eyebrows, while Asians prefer straight eyebrows; Caucasians prefer thick smoky eyeliner and eyeshadow, while Asians prefer natural-looking makeup that highlights but not necessarily accentuates the eyes; Caucasians prefer thick, full lips whereas Asians will try to apply lipstick in an area smaller than the actual lip size to downsize the volume of their lips; Caucasians generally have long, big noses with high bridges and tips, while Asians generally have and always prefer a smaller, shorter nose; Caucasians generally have broad, angular jaws and stronger chins, whereas Asians highly obsess over having a V-shaped or heart-shaped narrow jaw with soft, delicate chin.

The difference between Caucasian and Asian standards of beauty and idealized images of physical perfection are almost completely the opposite of each other, and you can see this most apparently when you compare the most popular celebrities from each culture, who each represent their culture's ideal beauty image.

So don't ever give the crap that Asians are trying to look Caucasian, because you just appear as racist, self-centered, self-biased and ignorant.

Ash — December 16, 2014

And in response of Post #1 by Han, Caucasian people are not worshipped by the overwhelmingly vast population of East Asian and Southeast nations.

I am a pure-bred Asian (Chinese) born and live in Asia all my life, and I can tell you this- Caucasian people are generally seen as strange, weird and foreign and many Asians will avoid Caucasian people because they are not used to seeing them.

Also, in our culture, a native Asian who dates a Caucasian is shunned and seen as an outcast of society, because she has chosen to give up her native culture and marriage prospects to a native Asian from her culture in order to defect to another culture. We have many negative labels for such local women who go out with Caucasian men.

Another thing is that Asian culture highly values homogeneity, and seek to keep traditions and lineages going along on a pure line, without taint from other cultures or races. The tradition is that we should always prioritize marriage to our own race and as I mentioned earlier, breaking or violating such an unspoken rule results in social discrimination.

The only kind of women here who worship Caucasian men are those who try to leech the money and status from wealthy Caucasian expatriates who come here to work. Which is another reason why our culture labels these women in a negative way.

Hallyu's Homogenisation of Beauty in Asia - seoulbeats | seoulbeats — April 14, 2015

[…] Times, The Society Pages, The Economist, Love Love China, Shanghaiist, CNN, Valentina Marinescu, Jonghoe Yang, CS […]

chal — December 23, 2015

Seriously, people should stop using fake images. Korean miss universe aren't look that similar to each other, people photospped it. It's true many people got plastic surgery in Korea, majority of them, but it's not that bad. There are many people who has the same traits (double eyelid, v jaw line) but not looking 90-99% the same like what people claim to be.

However, check out complete list of korean beauty standards for male, female, and foreigners.

chalimi

Archie — December 23, 2015

I have traveled the world extensively, to include Central and East Asia. As I read the article, I found so many misperceptions, mischaracterizations, and unsubstantiated assertions that I began to write a response. Then, reading through the comments, I arrived at Ash's first comment which clearly encapsulated many of my objections. Ash hit the nail on the head. Sadly, C.N. Le has revealed not only that he is culture-bound, but that his evaluation of Asian beauty ideals has been conducted through the foggy lens of an Asian-American with prominent inferiority and persecution issues.

Rachel — December 30, 2015

Replying to the first comment, Asians don't really try to look Caucasian (The Chinese have preferred light skin since at least the Warring States Period). I can't supply a reason for why except that there's no reason for them to *want* to, but I can provide examples of beauty being very different in Asia vs. Europe/USA. For example, aegyo sal in South Korea. There's a difference between aegyo sal and eye bags, but most Caucasians would probably ask why someone would use tape, makeup, and even surgery to get them. In addition, one only has to google "gyaru", a Japanese term, to see that the Asians strive for a more childlike appearance. Compare this to Americans, who focus on having a more sexy and mature appearance. Finally, eyebrows.

:)

Rachel — December 30, 2015

I forgot to add teeth; Japan has a yaiba trend that surgically unorganizes teeth to appear more childlike while America has braces, which slowly align teeth to seem more organized. Asians are not emulating Caucasians~ :)

Dan Collins — January 3, 2016

I think people should stop thinking in terms of victimisation, stereotypes and western oppression. The simple fact is that the world is flooded with variety and amazing beauty. My own sense is that narrow Asian eyes are incredibly beautiful. Others think otherwise. Why slag people's preferences, if no harm is being done? What I hate is oppressive pc.

The Westernization of Asian Beauty – Through Altered Eyes — January 22, 2016

[…] as C.N. Le mentions in a post about Asian beauty standards, elevated status of Europeans politically, socially and economically throughout history has placed […]

Anon — May 25, 2016

Ash, contrary to popular belief, Americans do not think we are the only country in the world.

Also, "pure bred" Asian? Seems to me like you're kind of racist, lol.

TOPIC: VOEL JIJ JE MOOI ZONDER MAKE-UP? – Selectedbye.nl — August 15, 2016

[…] zijn en waarom. Dit gaat zelfs zo ver, dat in sommige landen meiden totaal hier in doorslaan met de meest bizarre looks als gevolg. En dan te bedenken dat in de middeleeuwen neer werd gekeken op make-up door de […]

Rias — December 23, 2016

There's a difference between conscious imitation and subconscious influence. I think the latter is what the author is driving at, so there's no need to get all defensive. Beauty standards in East Asia are not "the exact opposite" of Caucasian beauty standards, or at the very least they are not the complete opposite of a Caucasian look which is really what this is about- not whether whites and Asians explicitly desire the same things. They're obviously different but there's no denying that they have been influenced by the international (white) order. Flat chests and small eyes, egg shaped faces, are examples of classical beauty in East Asia. The beauty standards of today are very different to those in ages past (obviously the ones I just listed were not always popular but they have all been so at one point or another), and they just so happen to have changed significantly alongside globalisation. Say what you will, larger eyes, sharper noses, and (sometimes) larger breasts all came into fashion after European contact. It's not a coincidence. It's the same way black women all need weave nowadays, that's not just some sort of huge coincidence. Wider social norms affect us, even if we don't consciously desire to be like white people or whoever it is at the time in question. It's not an amazing article, but it's not completely wrong as some people here are suggesting.

Post 3. Modern Beauty Standards – Korean Beauty Culture — May 29, 2017

[…] Source: https://thesocietypages.org/papers/homoegenization-of-asian-beauty/ […]