It has been weeks since I have crossed the stage, shook the hand of my college’s president, smiled at my family in the audience, and received my Bachelor’s degree. It struck me knowing that I had finally got to that very moment. The moment I had been waiting and working at for four whole years, and a bunch before that. Although I can thank my family for the endless support, thank my friends for the long nights of studying, and myself for remaining determined through absolutely everything—I also must thank my professors. Especially the professor who allowed me to reach my fullest potential, push me past my limits, and allowed me to see that I am capable of achieving whatever goals I set for myself. Virginia Rutter, the professor for the independent study, Margin to Center: Black Women in Policy, facilitated the unique class, where we talked to a lot of great women, including Cherrie Bucknor, a doctoral student in Sociology at Harvard University. Her research interests include class, race, gender, labor unions, and social policy. Previously, Cherrie Bucknor worked at the Center for Economic and Policy Research (CEPR) where she developed a series called Young Black America. Sitting across the table from her at lunch in Cambridge, I was able to hear all that she had to say about her series, her advice, and so much more:

TC: What advice do you have for Black women who want to attend an ivy league school?

CB: This is probably going to sound a bit ridiculous coming from someone who is currently at Harvard and who got their undergraduate degree from Penn, but I would encourage them to not necessarily strive to go to an “Ivy League School”, but to go to the school that they believe will be the best fit for them, both academically and emotionally. That should be the ultimate goal. As in many things in life, there will be sacrifices to make in these two areas (and others), but the goal should be to try and end up at the school that will maximize those two areas and others that are important to you. Oftentimes, when we think of college, we only think about the academic aspect. But, for me, both in the past and currently, the non-academic parts of my life on campus really help to keep me on a good page emotionally when I may be dealing with things in class or with my research that would otherwise keep me down.

I would also encourage them to speak with Black women who are already at the institution to hear from them what their experience has been like. Our experiences as Black women are unique in many ways and for me, it was invaluable to hear from the Black women who were already in my program. The Black women who paved the way for us will have advice on how to navigate the particular environment that you will find yourself in. Every school and department is different, with their own strengths and weaknesses, so it’s best to know as much going in as you can.

TC: What gets you through your days/moments when you are discouraged?

CB: The short answer to this would be “my people”. More specifically, I have a community of people, both in the Boston area and elsewhere who get me through the moments when I feel discouraged. This includes my parents, siblings, and other family members who have been on this journey with me since the beginning and who are just as invested in seeing me reach my goals as I am. The friends that I spent the past 5 years with in DC are just as much a part of my life as they were when I lived in DC. They are always there for me to vent to. They know just the right GIF or meme to send me that will make me literally laugh out loud.

Over the past year, I have also been lucky to develop friendships with fellow students in my department and throughout Harvard who I really vibe with on many different levels, whether it’s because we have similar research interests, political interests, experiences as scholars of color, or we watch the same TV shows or hate the same sports teams. While these friendships are relatively new, and some were unexpected, I can already tell that they will be “my people” for years to come.

Lastly, as I’ve mentioned above, the non-academic aspects of my life here also get me through the moments when I am discouraged. My work with our recently-certified graduate student union brings me so much joy because of the possibility of making Harvard a better place through the bargaining process. I have also been working with a great, diverse group of students who share my interest in prison abolition and who experience similar challenges as students of color on campus. Every week or so, I know that I’ll be sitting in a room with or on a conference call with people who are committed to doing good research and good work in our community. I feel very fortunate in that regard.

TC: Why did you choose to focus on Young Black America as a series when you were at CEPR? What was it like to conduct and then communicate this type of research?

CB: My Young Black America series was actually my first solo-authored work at CEPR and it was about 6 months into my time there. I say this all the time, but I definitely feel as though CEPR spoiled me as a young researcher. The latitude that I was given during my three years there was truly remarkable. This particular research came about because of a curiosity that I had. I really just wanted to answer the question “what’s going on with young Blacks in America right now”? As a young Black woman, I wanted to know how our community was doing. The recovery from the recession was going along too slowly in my opinion and I had heard a great deal about the experience of workers overall, or Black workers overall, and I wanted to see if the story was the same for young Blacks. I presented my idea to my office mentor and boss and they both were excited about it and basically told me that I could design the series however I want and they would support me.

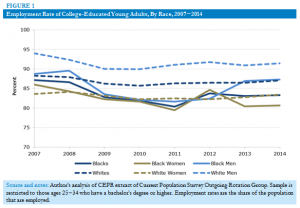

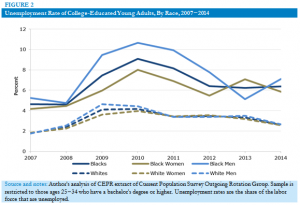

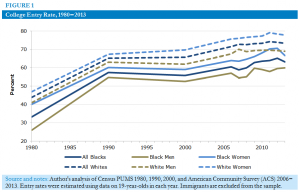

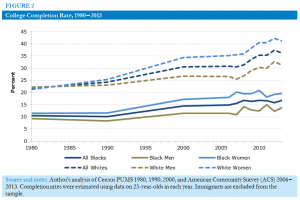

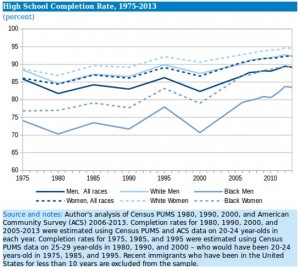

Given the fact that many people associate educational attainment and success with economic success, I decided to do the first two pieces on recent data on high school graduation rates, college entrance, and college completion. The third piece was about employment and unemployment rates, and the last piece was about wages. The series told a story of increasing educational attainment that has not necessarily translated to significant gains in employment and wages, leaving persistent racial and gender gaps.

As I mentioned above, this series was my first solo-authored work at CEPR. The very first piece in the series also ended up leading to my first interview with a reporter. To say I was nervous would be an understatement. I went into our communications director’s office and proceeded to vehemently protest against doing the interview and how I was sure I would make a fool of myself. However, after a mini media training session, I gained some semblance of confidence, or at least enough to go through with it, and it went perfectly fine. To this day, I still get nervous and worry whenever I have to speak to a reporter or do a radio interview, but I just remind myself of this: what good is it to do research that you think is important if nobody hears about it?

***

TC: Cherrie made it clear. As I move out of the world of undergrad and maneuver my way into a whole new environment in graduate school, having, as she puts it, “my people” when I get discouraged is exactly what I need. What is an important take away is that having “my people” will not be enough. I must make sure that I am focusing on myself too—the things that make me happy, the moments that bring me joy, and I must value my self-care because being a woman of color, the external social forces in our society are working against me. They do not want to see me rise nor do they want to see women of color shine. However, I must understand that since I am a woman of color, my self-care is revolutionary… and the bonds I create with other Black women as my future unfolds will be too.

Tasia Clemons is a recent sociology graduate from Framingham State University as well as a graduate assistant Hall Director at Canisius College. She tweets at @TasiaClemons. Cherrie Bucknor is a doctoral student at Harvard University and currently working on two projects: examining the union wage premium for young workers in the United States overall and by race and education level, as well as a project titled “Race, Economy, and Polity in the Trump Era.” She tweets at @CherrieBucknor.