Simone Ispa-Landa, Assistant Professor in the Department of Human Development & Social Policy at Northwestern University, is a new dear friend and fellow mama with a pen. A sociologist who researches adolescence, race and ethnicity, gender, and (most recently) stigma and the effects of criminal record labeling, she teaches courses on qualitative methods. She is fiercely feminist in her intersectional approach, a passionate scholar grounded in the here and now. Below, she responds to the current conversation about what Black parents can and should tell their kids about how to stay safe. It’s not Black families that are failing in their efforts to protect their children, she reminds us. And she’s got the analysis to back it up. Here’s Simone. –Deborah Siegel

Simone Ispa-Landa, Assistant Professor in the Department of Human Development & Social Policy at Northwestern University, is a new dear friend and fellow mama with a pen. A sociologist who researches adolescence, race and ethnicity, gender, and (most recently) stigma and the effects of criminal record labeling, she teaches courses on qualitative methods. She is fiercely feminist in her intersectional approach, a passionate scholar grounded in the here and now. Below, she responds to the current conversation about what Black parents can and should tell their kids about how to stay safe. It’s not Black families that are failing in their efforts to protect their children, she reminds us. And she’s got the analysis to back it up. Here’s Simone. –Deborah Siegel

Three weeks after George Zimmerman’s acquittal, it’s a good time to reflect on a curious conversation that has been unfolding in its wake – one about what Black parents can and should tell their kids about how to stay safe and survive. Obviously, these are great – and unfortunately necessary – conversation for families, and especially Black families, to have. But on a national level, I think we need a different conversation. Instead of talking about what parents can do and say to keep “at-risk” kids safe, let’s talk about how race matters for both “at-risk” and privileged kids.

Feminists working in the intersectionality framework have long noted that representations of Black women as bad mothers and Black men as absent fathers are important cogs in an ideological machine. This is the machine that produces images of Black youth as “bad seeds” – on the way to becoming high-school dropouts, dangerous criminals, irresponsible parents, or just plain poor.

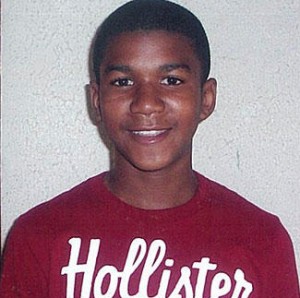

The recent events surrounding the shooting of Trayvon Martin only confirm the idea that Black youth – and especially Black males – face a world of hazard that most White people cannot even imagine. After all, how many White parents have to worry about their teenage sons being shot and killed when they leave the house to go to the store? Or face a court system that pretends to be “race-blind” and repetitively silences the very issues of race that lie at the heart of its most troubling cases?

That said, the entirely sad and perhaps utterly predictable unfolding of the Trayvon Martin case, from the moment the 17-year old first attracted the attention of an armed neighborhood watch volunteer as “suspicious” to the defense attorneys’ devious attempts to reconfigure our image of Trayvon Martin from victim to “dangerous Black male thug” – should force the nation to rethink the spurious notion that Black families – and especially mothers – are responsible for the tragedies that disproportionately befall their children.

Black families are not failing in their efforts to protect their children. Rather, it is the broader society – including the lingering effects of centuries of race-based exclusion, segregation, and cultural devaluation – that are making it so difficult for Black families to keep their kids safe. In fact, it’s possible that the whole notion of “at-risk” Black youth would fade into an old-fashioned anachronism if our public institutions were half as committed to the welfare of the next generations of Black youth as their families were.

Indeed, research by people like Signthia Fordham suggests that many Black parents engage in hyper-vigilant surveillance and monitoring of their children’s whereabouts, all to guard their children against the kinds of danger that more privileged parents don’t even have to consider. Further, while privileged suburban kids might bristle against their parents’ rules about cars, sex, homework, and drinking in bids to show off their autonomy, many Black kids in this country don’t have that luxury.

In my recent research, I examined how a sample of urban Black youth understood their parents’ rules and monitoring practices. The participants in my sample legitimized even fairly restrictive parental restrictions as reasonable – as appropriately attuned to the hazards they faced. The teens in my sample believed that following parents’ rules was critical for staying safe – and achieving future economic security. In fact, the accounts of the urban Black teenagers whom I interviewed strongly diverged from accounts of more privileged American teens, who researchers like Amy Schalet, author of Not Under My Roof: Parents, Teens, and the Culture of Sex, describe as rebellious and prone to “sneaking around” behind their parents’ backs. In my research, I theorized that the adolescents in my sample were different from more privileged (White) kids, in part because they could not afford to go off the straight and narrow. They didn’t have that freedom.

As many critical race scholars have argued, everyone in society is a racialized subject. Part of being White means benefiting from the fact that whiteness in American society still functions as the universal, high-status, and unstated “norm,” and non-whiteness as different, low-status, and visible. When white kids wander into their own or others’ neighborhoods, they are benefiting from the privileges that come from belonging to this “unmarked group.” And, as Trayvon Martin’s shooting shows, belonging to a group that is marked as different, low-status, and visible can be incredibly dangerous, regardless of how well (or not) your parents prepare you for this reality.

So, instead of dissecting all the things parents of “at-risk” kids – and the kids themselves – should be doing to stay safe, let’s start a new conversation about all the ways that society can shift to make this a place where it’s easier to be a parent, and where being a kid means having the luxury (even if only occasionally) to rebel – without paying a tragic price.

Comments 2

Letta Page — August 5, 2013

This article immediately brings to mind Rahsaan Mahadeo's write up of recent research on a new form of "concerted cultivation"--parents teaching their children to expect racism and learn strategies to deal with it so as to protect their own safety. The research was from ASR in 2012, and co-authored by Burt, Simmons, and Gibbons, and Mahadeo's short summary piece is here, on TSP's reading list: http://shar.es/yqLzx

What a striking, and telling, thing for parents to have to add to their toolkits: here are some ways to avoid conflict when you're directly attacked.

Natalie Wilson — August 7, 2013

What an excellent piece.

Your last paragraph about the need to change the conversation regarding what parents of "at risk" kids "should" be doing to what we as society needs to do reminds me of the way in which females are are told they "should" be doing various things to "stay safe" -- why is it the burden is so often placed on the people who, for lack of a better term coming to mind right now, are the "victims" of our racist, sexist, heterosexist and so on society?

This who "should" do things mantra seems to be one that desperately needs rethinking and is so key to all you discuss.