Tina Pittman Wagers is a clinical psychologist and teaches psychology at University of Colorado Boulder. She just survived a heart attack.

I am new to this role as a heart patient. My heart attack was five weeks ago, and I am getting the feeling that I have just begun down the confusing maze of angiograms, CT scans, EKGs, medications (and lots of ’em), heart rate monitors, cardiac rehab classes and blood tests. Indeed, even the phrase “my cardiologist” is one I never thought would pass my lips. Here’s why: I am 53 (we’ll discuss the significance of this age in a moment). I am fit, active, slim, haven’t eaten red meat for about 20 years and am a big fan of kale, salmon and quinoa, much to the chagrin of my two teenage sons. I live near the foothills in Boulder, Colorado, where I hike with my dog and often a friend or two, almost every day. I had completed a sprint triathlon two weeks before my heart attack. Ironically, this event was a fundraiser for women with breast cancer – it turns out that heart disease kills women with more frequency than breast cancer. But, hey, who knew?

My heart attack happened while I was swimming across a lake in Cascade, Idaho. I was about a quarter mile into the swim when I found that I couldn’t breathe, and was grabbed by an oddly cold and simultaneously searing band of pain about three inches wide across my sternum. My husband, Ken, was on a paddleboard nearby and helped pull me out of the water, and started paddling me back, stopping to allow me to vomit on the way back to shore. If you’ve never been on a paddleboard, it may be hard to imagine the balance it takes to paddle relatively quickly and keep the board from getting tipped over by the unpredictable movements of a heaving passenger in the midst of a heart attack. Suffice to say that I am grateful for Ken’s strength and balance in innumerable ways. An hour later, I was at a clinic in McCall, Idaho, where an astute ER doc was measuring my heart rate (very low) and heart attack-indicative enzyme called Triponin (rising) so I won an ambulance ride to St. Luke’s Hospital in Boise, Idaho. I received excellent care there, queued up for an angiogram the next morning and was diagnosed with SCAD: a spontaneous coronary artery dissection, and, fortunately, a relatively mild one. Twenty percent of SCADs are fatal. Furthermore, I have none of the typical risk factors for heart disease, like high blood pressure, diabetes or high cholesterol.

I do have one of the main risk factors for this kind of heart attack, though: I am a woman. Eighty percent of these heart attacks occur in women. The average SCAD patient is 42, female and is without other typical risk factors for heart attacks. The current thinking about SCADs is that they are not as rare as originally thought, but are under- diagnosed because they happen in women who don’t look like typical heart patients.

Another related factor: I am menopausal. The majority of SCAD patients are post-partum, close to their menstrual cycle or menopausal – all times in women’s lives during which we experience significant fluctuations of sex hormones. Up until five days before my heart attack, I had been on low doses of Hormone Replacement Therapy (HRT), in an effort to vanquish the hot flashes, sleep disruption and cognitive fogginess I was experiencing. I suppose HRT might have also represented an attempt to hang on to youth, in a youth-and sexuality-obsessed culture in which the transition to menopause often means a dysregulated and sweaty march into irrelevance.

Since I had my heart attack, I’ve spent a lot of time (and money, but that’s another column) interacting with professionals in the cardiology world, trying to figure out what happened to me, and how I can avoid having another SCAD – the rate of recurrence in my population is about 20-50 percent. I have encountered some lovely people, but almost all of them are baffled about what to do with me. I am atypical, as they inevitably explain, but the medications, the treatments, the rehab programs that they have to offer are designed for typical patients. So, that’s what my doctors try, but there is a lot of “voodoo vs. science” as one cardiologist explained, because science doesn’t have the answers to my questions. (I would add that there is a cardiologist, Dr. Sharonne Hayes at The Mayo Clinic, who is doing a lot of the research and seeing the patients who’ve had SCADs. I hope to meet her one day. I imagine a scene something like my 13-year-old self meeting David Cassidy, only in an exam room in Rochester, Minnesota– it’ll be just that cool.)

One of the factors that contributed heavily to my medical predicament was no doubt my menopausal and HRT status. The American Heart Association points out that lower estrogen levels in post-menopausal women contributes to less flexible arterial walls, clearly a factor in SCADs. The question then arises: how might HRT help prevent another heart attack? However, as anyone who’s even scratched the surface of the HRT world, there is a lot of conflicting data about who should use HRT, who shouldn’t, what the benefits and risks are, and what the differences may be between different formulations and methods of delivery of HRT. One study, the Women’s Health Initiative study, was a large study started in the early 1990s, and was a valiant attempt to gather data about the effects of HRT on women’s health, including cardiovascular health. Unfortunately, the average age of the women in this study was 63 – 12 years older than the typical age of the American woman hitting menopause and considering HRT, so the results have been criticized for their poor generalizability to newly menopausal women. The research on HRT since the WHI study has been scattered, often contradictory, and hard for the average woman to access.

Why do we know so little about women and heart attacks, why they happen, what the symptoms are, and what we can do about hormonal factors that contribute? A big part of the problem is that, until the National Institute of Health (NIH) Revitalization Act in 1993, researchers largely excluded female humans from their studies. NIH has just this year (2014!) decided to use a balance of male and female cells and animals in their research. Up until now, 90 percent of the animal research has been conducted on males. Animal research, which is often a precursor to clinical trials in humans, has been missing out on vast pieces of investigation related to the female body. I am living (fortunately) proof of the fact that the delays in including females in research have translated into significant gaps in clinically relevant knowledge related to women’s health. Well-meaning physicians and practitioners only have the “typical” approaches to try with their “atypical” patients. Why this appalling delay to include female subjects? Because female rodents as well as humans experience menstruation and menopause, which are frequently considered dysregulating nuisances to many scientists. As a consequence, we have an enormous amount of catching up to do in order to understand what factors affect female bodies and health problems in different ways than our male peers.

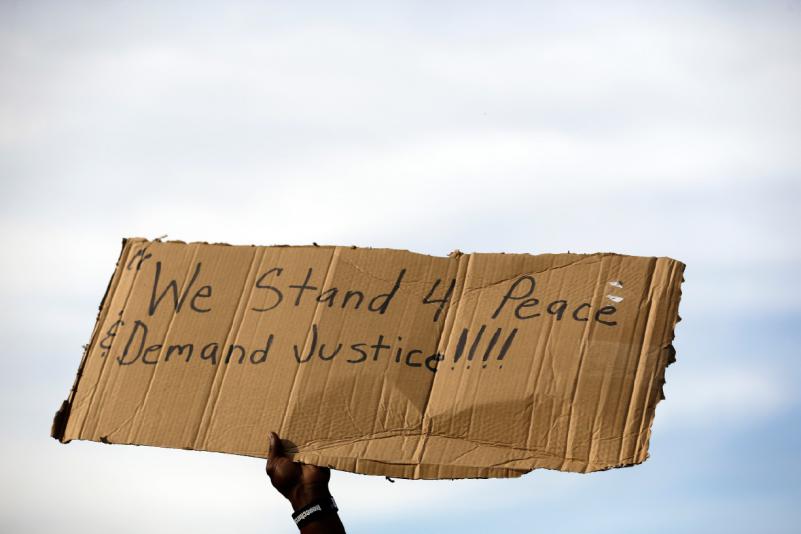

Emma Watson gave a great talk last week to the UN about feminism meaning equal access to resources. One of the most important resources we have is scientific knowledge that can be applied to responsible, effective and efficient clinical care. Let’s hope that women can start to be understood as typical research subjects and patients, not as inconvenient, fluctuating, atypical anomalies.