Author, Paradise Transplanted: Migration and the Making of California Gardens (University of California Press 2014)

___________________________

Are flowers feminine and lawn masculine? Or are gardens, with their domestic allure and food provisioning, feminine altogether? Thinking about gender as a duality of flowery femininity and masculine mowing doesn’t get us very far. It’s like trying to squish bio-diversity into a binary code. We know gender is shaped by intersections of race, class and nation, by myriad subcultural groups and by everyday acts of gender bending and deliberate non-compliance. So what do we see when we look at the residential garden as a project of gender?

The lawn is the obvious place to start. The American suburban lawn once received derisive commentary from urbanites and novelists but now, as the entire western portion of the United States fries after years of drought, anti-lawnism is catching on with many sensible people. But who insisted on front yards of lawn in the first place? Suburban homes set back from the street, with ornamental plants around the foundation of the house and lawn stretching out to the street is a style attributed to Andrew Jackson Downing (1815-52), the nation’s first popular garden designer, merchant and Martha Stewart-like tastemaker. He loved the lawn. In his 1841 book, he instructed Americans on how to have a garden in good taste: men should tend the lawn, walkways, vegetables and fruit trees, and women, the flowers. Jane Loudon’s Gardening for Ladies, published in England around the same time and widely read in the U.S., cautioned women not to over-exert themselves in the garden. Meanwhile, lawn as a symbol of masculine status and power, was marketed to men by lawn mower companies as early as the 1850s.

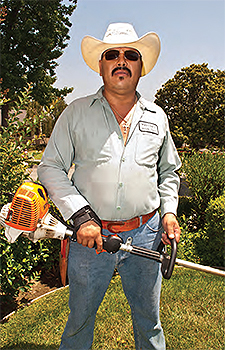

As the suburbs expanded in late nineteenth-century America, the man mowing the lawn and the lady as manager of the home and garden defined new gender ideals that reached their apogee when the GI Bill swelled the ranks of suburban home owners. Today, this gendered template of women tending to life in the domestic interiors and men tending to the domestic exteriors still lingers, but it’s now a shadow. Gendered household divisions of labor have loosened and they have also been outsourced to others. In affluent communities around the nation, from Los Angeles to Long Island, it is increasingly Latina/o immigrant women and men doing this work. Latina women are cleaning and caring indoors, and Latino immigrant gardeners are tending to the plant life and the dirty work of mowing lawns and blowing away fallen leaves outdoors.

Domesticas and jardineros are gendered mirror images, dual vestiges of nineteenth- and twentieth-century ideals that take shape in new racial, immigrant, and class formations. While men of color undergo surveillance in many public and upscale places, Latino immigrant gardeners freely circulate in white middle-class and upscale neighborhoods and stride through private gates into other people’s backyards. Their tool-laden trucks and mowers and blowers serve as their passports, allowing them to do gendered labor in other people’s private property.

Latino immigrant men are doing the hard work in residential gardens across the nation, but gardening still registers as flowery and feminine, calling to mind images of earth mother. Gardening, like motherhood, is associated with virtue, integrity, and morality and it is something women are supposed to want to do. In my interviews with homeowners, men were not lusting for a chance to mow the lawn, but women yearned to grow flowers and herbs, to savor a moment of rest on the front porch. The women voiced wistful aspirations of “I should be in the garden” as they listed their many obligations and activities. No one—really, no one!—wished to mow the lawn. That iconic masculine performance of home-ownership has now become a quaint mid-twentieth-century relic in Southern California, and in other regions of the U.S. Professional class men who employ paid gardeners can now focus more on their leisure and relationships, easing their time-binds so they can be more present as fathers and soccer dads, as Hernan Ramirez and I underscore in a book with UK colleagues. It is the domestic labor of Polish immigrant handymen in the UK and Latino immigrant gardeners in the U.S. that make that possible.

Using a migration lens and intersectional perspective helps us to see the gendered garden in a new light. It’s not pink and blue, but it’s brown, and brown men’s labor allows for a blurred gender division of labor in households privileged by class, race and nation. The outsourcing of domestic exterior mowing, trimming, pruning and cleaning allows for new shifts in gendered household divisions of labor, freeing privileged men from some of their domestic masculine housework, and maybe opening doors to other types of family work. Global migration is part of the shared landscape now.

Our arguably coolest first ladies, Eleanor Roosevelt and Michelle Obama, symbolically picked up a shovel and dug White House gardens. But of course they too outsourced the hard work of turning soil and making compost. Does that make the efforts of these uber earth mothers of the nation any less significant? I think not. Let’s look beyond the binaries of pink and blue, and strive for a world where environmental sustainability accompanies social justice and a cultural sustainability based on recognition and just remuneration for Latino gardeners.

Comments 1

From Pink and Blue to Brown: Gendering the Garden | — August 18, 2014

[…] piece was cross-posted with permission from Girl W/ Pen. To view the original piece, click […]