I just finished reading the June issue of Poetry magazine, which features the landay, an oral form of poetry popular among Pashtun women in Afghanistan.

You should really just go read the issue here. But here’s a quick description:

The landay is an anonymous and collective tradition with origins in the Indo-Aryan caravans of thousands of years ago. These couplets were traditionally sung to the beat of a hand drum. “Landay” itself means “short, poisonous snake,” and it can indeed bite like a snake: quick and frequently acerbic, the landay is only twenty-two syllables long, with nine syllables in one line and thirteen in the other.

Here’s an example of one:

You sold me to an old man, father.

May God destroy your home, I was your daughter.

Landays are a form in which women can voice a rage of feelings—love, longing, anger, desire, lust, pride, nationalism, and grief—while remaining anonymous. Because they’re constantly repeated and remixed, they’re not about the speaker personally. At the same time, they are about the speaker, because different landays resonate with different individuals.

Landays are often shared in secret. Men don’t hear women speak or sing them. As a consequence, they can be subversive in multiple ways.

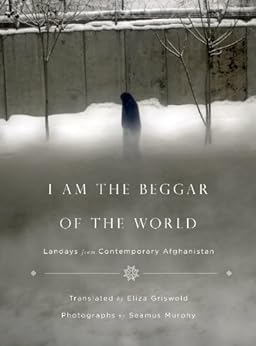

The poet-journalist who translated these landays, Eliza Griswold, worked with photographer Seamus Murphy in Afghanistan to collect as many landays as possible. Their collaboration resulted in the stunningly beautiful issue of Poetry (which also features some fabulous commentary by Griswold) as well as a forthcoming collection, I Am The Beggar Of The World: Landays From Contemporary Afghanistan, pictured above.

(If you’re really interested, Seamus Murphy has made a short film, Snake, with more images and audio that includes recitations of landays in Pashto and English. There’s also an older collection of landays, called Songs of Love and War: Afghan Women’s Poetry, originally collected and translated into French by the poet Sayd Bahodine Majrouh during the civil war in the 1980s, and then translated into English by the distinguished Marjolijn de Jager. Oh, and check out the Facebook page on landays as well.)

Despite all the writing about Afghanistan in the West—the journalism, the policy papers, the political pronouncements—these poems remind us of the voices that are shut out of the halls of power. Their lines suggest deep and often bitter feelings about the U.S., the Taliban, and the years of war and foreign occupation. One landay dating back to the nineteenth century used to be about a British soldier, but today it has changed:

My lover is fair as an American soldier can be.

To him I looked dark as a Talib, so he martyred me.

Many of these poems are political and speak with rage about loss and destruction.

The speakers of these landays aren’t voiceless victims. I’m reminded of Lila Abu-Lughod’s critique of the rhetoric around “saving” Afghan women that was used to justify the U.S. invasion of Afghanistan in 2001. What happens when we construct the Afghan woman as someone as in need of saving, she asks: “What violences are entailed in this transformation, and what presumptions are being made about the superiority of that to which you are saving her?”

By contrast, these poems reveal a complex portrait. They speak of the ongoing oppression of Pashtun women, many of whom are illiterate—but they also suggest women’s agency and depth as human beings.

They also hint at the complex position of Pashtun women in ways that resonate with women’s postcolonial writing from other regions of the world. Feelings of nationalism—fostered in resistance to occupation and imperialism—vie with critiques of patriarchy. Gender matters, but it’s certainly not the only problem.

Most of all, I’m struck by how many of these landays speak openly about desire and lust. More than anything, this theme counters the image of Afghan women as victims. I won’t quote the bawdiest ones (they might make Shakespeare blush!), but here’s one to end on:

Is there not one man here brave enough to see

how my untouched thighs burn the trousers off me?

I’m eager to see more feminist scholarship on Afghan women’s poetry—and to read more landays.

Comments