Part 4 in a Series

I know racism exists everywhere in the U.S., but as a newer person to the South, I have observed that segregation and racism are more visible and verbal here.

Prior to moving here, I lived in the inner-city of a metro area in the Upper Midwest where I observed racism in more covert ways: minority youth afraid of police, wedges between different racial/ethnic groups in the community, and strategies to work on these issues from “Facing Race” trainings and community-police relationship building, to the police force trying to hire more minorities. From a vantage point of moving from the Upper Midwest to the Deep rural South, racism can be seen differently.

“Standpoint” is not a new concept to sociologists, nor to people of color who have lived in both regions. And certainly all ways that racism is expressed and experienced is unacceptable. However, some folks I have talked to who moved to the North from the South have said that when racism is more overt, it is sometimes easier to deal with because you know what people think. Whatever the form, racism is something we shouldn’t have to fight. But as I share my observations to talk about why black lives matter, I see clearly that racism is not dead.

In this post, I am going to take a different stance from my co-bloggers on Feminist Reflections to share stories that demonstrate racism in everyday interactions, rather than the local or national protests currently underway. Organized protests are the manifestations of years and year of oppression; a build-up of blatant racist acts experienced by people of color. With permission, I share the following stories from one of my students. My student “Bob” (not his real name) is currently finishing his internship under my supervision. It is my ethical decision to write more generically about my student and some events to protect identities of persons and organizations.

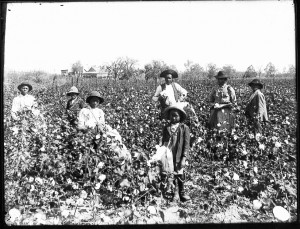

Pickin’ Cotton: My Student’s Story

Bob is a large black man. Bob knows he is large. Bob also knows how people may perceive him, given the stereotypes about back men. Indeed, he’s told me about numerous times in his life of being pulled over by the police and the interactions that have happened. But the reason I want to talk about Bob is to point to issues about language and micro-aggressions as a form of racism occurring in everyday lives. Everyday interactions, including our language, whether people “intend” to be racist or not, are embedded in structural racism.

In a meeting discussing his internship, Bob told me about something that happened with a man who answered the phones at his internship site. While waiting to meet with another person at the organization, they engaged in small talk. After a rant about how people claim their race and ethnicity, the man told Bob that he could not call himself African American, charging that Bob could not trace his ancestry back to slavery or to Africa. Bob was shocked that this man had the audacity to make such a ridiculous claim. In trying to keep his cool while also advocating for himself, Bob gave the man “a short history lesson.” But while doing so, Bob had to maintain professionalism as an intern, despite what he had just heard, which of course upset him.

There were other stories Bob shared. Since we live in the rural South, we are surrounded by many cotton fields. When Bob was talking to another person at the organization, the guy told Bob “to go pick cotton.” A cotton field was, literally, behind them. Joking or not, why would he say that? Did he fail to realize that the remark harkens back to slavery? Why did the receptionist at Bob’s internship think he could tell Bob what racial or ethnic term he can or cannot claim or use?

Why did these people express these particular words and types of sentiments to Bob?

Rest assured, Bob handled the situations with professionalism and dignity. He brought the issues to the person in charge of the organization, who was concerned and took action.

However, as Bob and I talked about his experiences and I thought about them for days, the question about who tells a black person to go pick cotton kept coming to back to my mind. Language matters. Symbolism matters. If someone doesn’t understand why telling a black person to go pick cotton is not okay, that person may want to re-visit history.

The issues were taken care of internally before I had to get involved as a faculty internship adviser. But hearing about these daily micro-aggressions Bob was experiencing made me angry. If I had to get involved, what would have I said? I would have to use the language of treating my student with respect, in which racism will not be tolerated. But “who tells a black person to go pick cotton?” This is the question to ask in these kinds of circumstances.

My student may be “privileged” in that he is attending college, but this does not erase his race, the discrimination he may face because of it, nor his feelings when racial aggressions occur. He knows that in a professional setting in which many things are at stake including the security of his internship, which may be a stepping stone to a job and/or letters of recommendation for his future, he must tread lightly. As sociologists have shown, if a black person gets angry it is often viewed stereotypically as typical behavior, helping to reproduce the cycle of racism. Bob advocated for himself, but realized that he had to do so within the constraints of his professional setting.

While this interaction is not at the same level as the Ferguson or related cases, it shows how micro level interaction racism exists in overt ways. A black person carries the burden of experiencing racism in everyday life.

Moving Forward

Beyond advocacy and social action through protests, rallies, and so forth, we must also listen and acknowledge the experiences of students and people of color that happen in everyday interactions. It is through some of these everyday experiences where we can see the ways in which racism is experienced on a daily basis by people of color.

These stories show the power of language, part of our (racist) culture. Micro-aggressions, including language and symbols, are symptoms of structural racism and perpetuate racism, intentionally or not. Intent is not the same thing as impact. And Bob is one of many students who have told me about these kinds of everyday racist interactions. Language matters. Unfortunately, language is often ignored.

I have encouraged my students to write about their experiences. My students have told me that they want to make a difference in the world and work for social justice in their careers and volunteer activities. Many of them in fact work or volunteer with student organizations, multicultural centers, and/or do internships at organizations that work with diverse and oppressed clientele. By documenting and reflecting on their experiences (sadly including the “isms” they experience or see others experience), using their sociological training, and reflecting on current ways of addressing inequality they witness, I hope we can find effective ways to work together to advocate for social justice. While I firmly believe that the oppressed should not have to teach their oppressors, I do think it is important for us as allies to listen and learn from the perspectives of people of color.

Often in our quest for public and feminist sociology, we do not hear from students or from those who experience everyday racism. I have invited my students to write their stories and reflect on how they conceive of advocacy and social change. We’ll share some of these on Feminist Reflections in the future to highlight student voices that exemplify feminist sociological principles. Activism through rallies, protests, and other forms of collective organizing are incredibly important, and so is listening and being there for our students.

In conclusion, please remember:

We cannot forget to be allies by LISTENING, leaning from, and supporting our own students whose lives have been affected by structural racism and experience micro-aggressions and every day, often overt, racism.

Related:

When Will the North Face Its Racism? by Isabel Wilkerson, The New York Times, Jan. 10, 2015

Read the entire Black Lives Matter Series on Feminist Reflections

- Part 1: Don’t Black Lives Matter? by Gayle Sulik

- Part 2: How Sociologists Can Support Black Lives Matter by Mindy Fried

- Part 3: An Open Letter to Student Activists by Meika Loe

- Part 4: Racism is not Dead: Language And Everyday Interactions by Trina Smith

Comments 1

Gayle Sulik — January 12, 2015

This piece is especially poignant, Trina. You point out that while organized protests are manifestations of years of oppression and a build-up of blatantly racist acts, everyday interactions and cultural cues seed racial inequality from the ground up, and in the most common places. This focus on micro-aggressions and front stage/back stage performances provides solid grounding for understanding the home grown character of racialized interactions within a complex matrix of social roles. Thank you for sharing your student's experience, and to your student for sharing it with you.