Part 2 in a series

Last Thursday night, I sat in Boston’s Hope Church with over 300 white people, not for a concert or for a sermon. But to respond to a call from local and national Black leadership asking white people to come together to talk about our role in the movement for racial justice. Like so many people, I had been seething about the targeting of young Black men by police, and the increasing militarization of the police in responding to legal protests in Ferguson and elsewhere.

I had joined two of the rallies in Boston the week before, the first, following the non-indictment of Darren Wilson, who had killed Michael Brown, in which thousands of people took over the streets, chanting “No justice, no peace, no racist police.” We paused in front of the South Bay House of Correction, where inmates stood at the windows with their arms held up to communicate “Hands up, don’t shoot.”

Ultimately, many of the marchers shut down a ramp leading to the interstate. In contrast to the media framing of this demonstration, a number of people I know personally were punched in the head or ribs, or trampled on by police. The other rally followed the non-indictment of Daniel Pantaleo, the police officer who killed Eric Garner, marching up to the city’s Christmas tree lighting and celebration. The message was that we cannot go on with business as usual, while Black people are being victimized.

Ultimately, many of the marchers shut down a ramp leading to the interstate. In contrast to the media framing of this demonstration, a number of people I know personally were punched in the head or ribs, or trampled on by police. The other rally followed the non-indictment of Daniel Pantaleo, the police officer who killed Eric Garner, marching up to the city’s Christmas tree lighting and celebration. The message was that we cannot go on with business as usual, while Black people are being victimized.

In both of these rallies, I was struck by the power of Black women leadership, and discovered the organizers of these events were from a group called Black Lives Matter (BLM) Boston, affiliated with the national BLM.

In both of these rallies, I was struck by the power of Black women leadership, and discovered the organizers of these events were from a group called Black Lives Matter (BLM) Boston, affiliated with the national BLM.

BLM is a national organization with an action agenda. It started as a hashtag, created by three Black queer women organizers with a deep understanding of “intersectionality” (or, ways in which different oppressions – including gender, race, and sexual preference – intersect and co-produce one another). Queer is an umbrella term to refer to all LGBTIQ – lesbian, gay, bi-sexual, transgender, intersexual and questioning people – that reveals the fluidity of social categories such as sex and gender. As Black feminist and social activist, bell hooks, writes: “Every day of my life that I walk out of my house, I am a combination of race, gender, class, sexual preference and religion or what have you.”

To be in a huge throng of people demanding an end to racism, to chant Black Lives Matter, was nothing short of inspiring. Here is a short clip of activist Ife Franklin, who spontaneously led us in singing Bob Marley’s “Redemption Song.”

Video from Ferguson Rally (11.25.14)

But while marching, there were moments I felt confused. Should I, as a white woman, be chanting, “Hands up, don’t shoot?” or “We can’t breathe?” Do whites as a group face systematic victimization by the police? No. Can I breathe when I see a police officer when I walk down the street? Hell, yeah! They might even help me, if I’m in need, without presuming that I am guilty of some infraction. As a collectivity, white people are not incarcerated or murdered because of the color of our skin. It seemed wrong to use the language of people who are.

I wondered, more broadly: What is my role in this struggle for racial justice, as a white person?

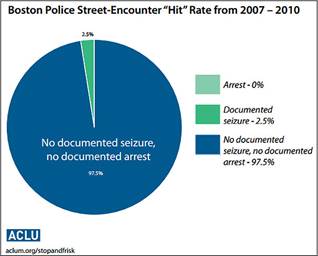

When I read about the local meeting to help white people figure out their role in the context of this organizing effort, I was compelled to go. Sitting in the pews of Hope Church, I listened to three young white organizers deftly walk us through a set of guidelines to frame how we can be allies – or “accomplices” – to this Black led movement “without replicating racist dynamics.” To set the stage, the trainers began by presenting findings from a study (conducted by scholars from Harvard and Rutgers for the ACLU) that confirmed the existence of racial discrimination within the Boston police force. The study concluded that Boston police officers disproportionately interrogated, observed, or searched Black residents during the period between 2007 and 2010.

And despite these Boston “police-street encounters,” there was little evidence of probable cause. Researchers reported that the “hit” rate was incredibly low, with no documented seizure and no documented arrest in 97.5 percent of the cases. Black people were 8.8 percent more likely than whites to be stopped repeatedly by police, and 12 percent more likely than whites to be frisked or searched during a stop.

In defining our role as white people in supporting Black Lives Matter, the trainers acknowledged that we in the audience might be leaders in our own worlds and in many of our endeavors, but now we have an opportunity to “follow the leadership of this Black-led, women-led, and queer-led movement.” They challenged us to keep “Black lives at the center,” meaning that it is Black people who suffer the consequences of anti-Black racism, and they must be in charge of the movement to eradicate it.

White people need to critically assess what it means to be white in a society that systematically privileges whiteness. Peggy McIntosh, who writes extensively on white privilege, says,

“I have come to see white privilege as an invisible package of unearned assets which I can count on cashing in each day, but about which I was ‘meant’ to remain oblivious…White privilege is like an invisible weightless backpack of special provisions, maps, passports, codebooks, visas, clothes, tools and blank checks.” [She cites many examples of white privilege.]

“Whether (I use) checks, credit cards, or cash, I can count on my skin color not to work against the appearance of financial reliability. I can arrange to protect my children most of the time from people who might not like them. I can swear, or dress in second hand clothes, or not answer letters, without having people attribute these choices to the bad morals, poverty, or the illiteracy of my race…I can do well in a challenging situation without being called a credit to my race…I can take a job with an affirmative action employer without having co-workers on the job suspect that I got it because of race…I can choose public accommodation without fearing that people of my race cannot get in or will be mistreated in the places I have chosen.”

White people have a critical role to play, not only in supporting the efforts of Black people, but also in educating ourselves and other white people about the nature of structural economic and racial oppression.

How can white sociologists contribute to a Black-led movement for racial justice? What role can we play in combating racism?

We may say, “I am not a race scholar,” so what can I do? But sociologists specializing in any field are still human beings living in a racist society. We understand the social structures within society that reproduce inequities of all kinds. How can we bring this sociological eye to our work to address and help to eradicate racial oppression? I can think about a number of ways, and maybe you can think of others.

We can assess the critical role of law enforcement as the tool of a white dominant culture. We can question how police brutality against “racialized others” has historically been considered acceptable in our society. We can change our curriculum and incorporate other people’s experiences and narratives. We can include authors on our syllabi who tell stories about racial injustice, providing students with a better understanding of the systemic ways that discrimination is reproduced. We can create space in the classroom for dialogue about these issues. And for those of us who teach social movements, we can include this growing social movement as part of our curriculum, how small acts of coordinated resistance are important for engendering large-scale struggle. We can also incorporate a race lens into our research and writing. We can support social action among our students on campus.

The trainers emphasized that Black Lives Matter is not a pep rally or protest; It is an uprising, and the meeting at Hope Church was held in the hopes that white people in the room would join that resistance. The three energetic trainers asked us white people to understand the structural nature of racism and to find a way to talk – as white people – about the Black Lives Matter movement. They asked us to commit to the practice of talking with other white people about white supremacy, just as we were doing at this meeting. And they asked us to become activists, to mobilize anti-racist white people when we were called upon.

As white people, we have an opportunity to make a difference, just as hundreds and thousands of white people who have joined the struggle for racial justice over the decades. As social scientists, we have tools to support this movement – our teaching and research and our access to spaces to foster a new, constructive dialogue – where we can frame the conversation for our students, our colleagues, and our communities.

To paraphrase an oft-used phrase: If not us, who? If not now, when?

Lyrics, Redemption Song by Bob Marley

Emancipate yourselves from mental slavery;

None but ourselves can free our mind.

Wo! Have no fear for atomic energy,

‘Cause none of them-a can-a stop-a the time.

How long shall they kill our prophets,

While we stand aside and look?

Yes, some say it’s just a part of it:

We’ve got to fulfill the book.

Won’t you help to sing

These songs of freedom? –

‘Cause all I ever had:

Redemption songs –

All I ever had:

Redemption songs:

These songs of freedom,

Songs of freedom.

Read the entire Black Lives Matter Series on Feminist Reflections

- Part 1: Don’t Black Lives Matter? by Gayle Sulik

- Part 2: How Sociologists Can Support Black Lives Matter by Mindy Fried

- Part 3: An Open Letter to Student Activists by Meika Loe

- Part 4: Racism is not Dead: Language And Everyday Interactions by Trina Smith