In 2014, a story in The New York Times by Seth Stephens-Davidowitz went viral using Google Trend data to address gender bias in parental assessments of their children—“Google, Tell Me. Is My Son a Genius?” People ask Google whether sons are “gifted” at a rate 2.5x higher than they do for daughters. When asking about sons on Google, people are also more likely to inquire about genius, intelligence, stupidity, happiness, and leadership than they are about daughters. When asking about daughters on Google, people are much more likely to inquire about beauty, ugliness, body weight, and just marginally more likely to ask about depression. It’s a pretty powerful way of showing that we judge girls based on appearance and boys based on abilities. It doesn’t mean that parents are necessarily consciously attempting to reproduce gender inequality. But it might mean that they are simply much more likely to take note of and celebrate different elements of who their children are depending on whether those children are girls or boys.

In 2014, a story in The New York Times by Seth Stephens-Davidowitz went viral using Google Trend data to address gender bias in parental assessments of their children—“Google, Tell Me. Is My Son a Genius?” People ask Google whether sons are “gifted” at a rate 2.5x higher than they do for daughters. When asking about sons on Google, people are also more likely to inquire about genius, intelligence, stupidity, happiness, and leadership than they are about daughters. When asking about daughters on Google, people are much more likely to inquire about beauty, ugliness, body weight, and just marginally more likely to ask about depression. It’s a pretty powerful way of showing that we judge girls based on appearance and boys based on abilities. It doesn’t mean that parents are necessarily consciously attempting to reproduce gender inequality. But it might mean that they are simply much more likely to take note of and celebrate different elements of who their children are depending on whether those children are girls or boys.

To get the figures, Stephens-Davidowitz relied on data from Google Trends. The tool does not give you a sense of the total number of searches utilizing specific search terms; it presents the relative popularity of search terms compared with one another on a scale from 0 to 100, and over time (since 2004). For instance, it allows people selling used car parts to see whether people searching for used car parts are more likely to search for “used car parts,” “used auto parts,” or something else entirely before they decide how to list their merchandise online. I recently looked over the data the author relied on for the piece. Stephens-Davidowitz charted searches for “is my son gifted” against searches for “is my daughter gifted” and then replaced that last word in the search with: smart, beautiful, overweight, etc.

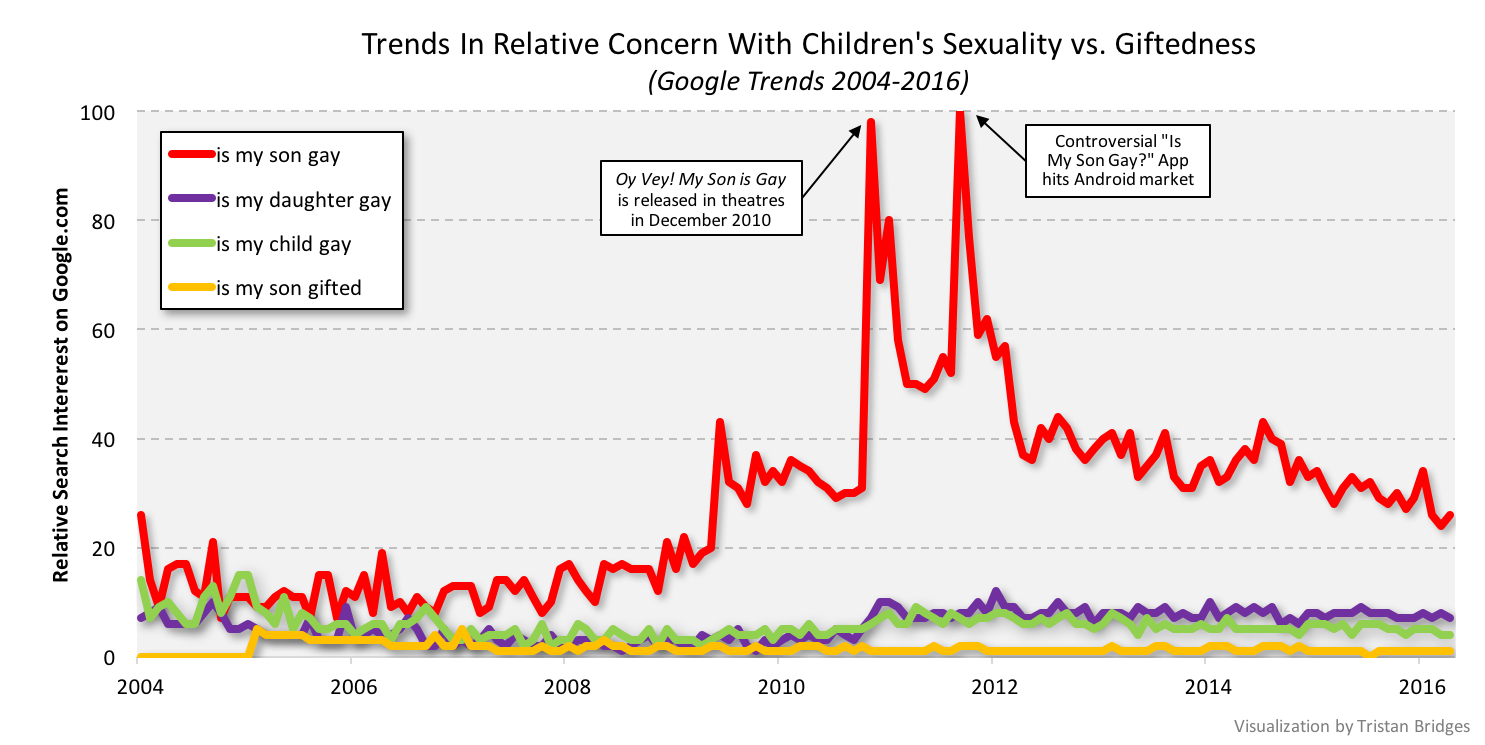

And while people are more likely to turn to Google to ask about their son’s intelligence than whether or not their daughters are overweight, people are much more likely to ask Google about children’s sexualities than any other quality mentioned in the article. And to be even more precise, parents on Google are primarily concerned with boys’ sexuality. Below, I’ve charted the relative popularity of searches for “is my son gay” alongside searches for “is my daughter gay,” “is my child gay,” and “is my son gifted.” I included “child” to illustrate that Google searches here are more commonly gender-specific. And I include “gifted” to illustrate how much more common searches for son’s sexuality is compared with searches for son’s giftedness (which was among the more common searches in Stephens-Davidowitz’s article).

The general trend of the graph is toward increasing popularity. People are more likely to ask Google about their children’s sexuality since 2004 (and slightly less likely to ask Google about their children’s “giftedness” over that same time period). But they are much more likely to inquire about son’s sexuality. At two points, the graph hits the ceiling. The first, in November of 2010, corresponds with the release of the movie “Oy Vey! My Son is Gay” about a Jewish family coming to terms with a son coming out as gay and dating a non-Jewish young man. The second high point, in September of 2011, occurred during a great deal of press surrounding Apple’s recently released “Is my son gay?” app, which was later taken off the market after a great deal of protest. And certainly, some residual popularity in searches may be associated with increased relative search volume since. But, the increase in relative searches for “is my son gay” happens earlier than either of these events.

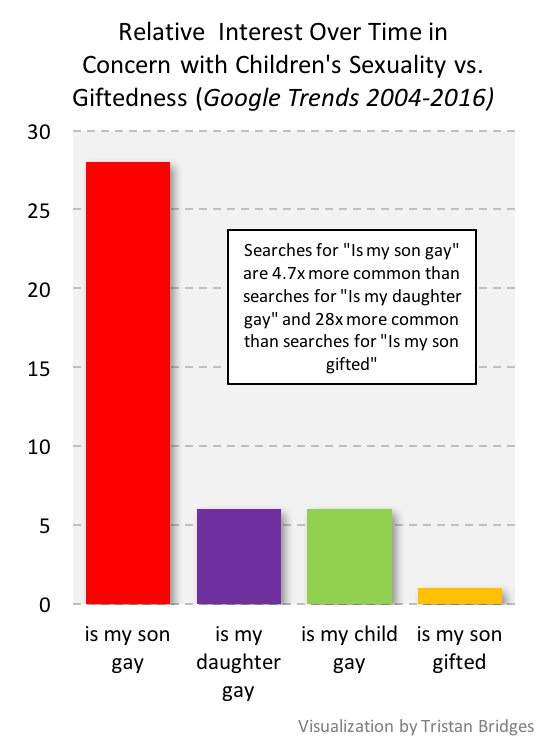

Indeed, over the period of time illustrated here, people were 28x more likely to search for “is my son gay” than they were for “is my son gifted.” And searches for “is my son gay” were 4.7x more common than searches for “is my daughter gay.”

Indeed, over the period of time illustrated here, people were 28x more likely to search for “is my son gay” than they were for “is my son gifted.” And searches for “is my son gay” were 4.7x more common than searches for “is my daughter gay.”

Reading Google Trends is a bit like reading tea leaves in that it’s certainly open to interpretation. For instance, this could mean that parents are increasingly open to sexual diversity and are increasingly attempting to help their children navigate coming to terms with their sexual identities (whatever those identities happen to be). Though, were this the case, it’s interesting that parents are apparently more interested in helping their sons navigate any presumed challenges than their daughters. It could mean that as performances of masculinity shift and take on new forms, sons are simply much more likely to engage with gender in ways that cause their parents to question their (hetero)sexuality than they used to. Or it could mean that parents are more scared that their sons might be gay. It is likely all of these things.

I’m not necessarily sold on the idea that the trend can only be seen as a sign of the endurance of gender and sexual inequality. But one measure of that might be to check back in with Google Trends to see if people start asking Google whether their sons and daughters are straight. At present, both searches are uncommon enough that Google Trends won’t even display their relative popularity.

Comments 2

Blumenberg — June 30, 2016

Very interesting. Many thanks for sharing. It might not change much, but I'd liked to have searches for "Is my daughter a lesbian" included. Or that possibility at least mentioned.

Kristin — August 21, 2016

Great article. I'd like to see the trend over a longer period of time, though, because as you can see after 2012 the search for "is my son gay" drops substantially.