Beth Schneider was the chair of my department the year I was hired and retired last winter. During the time I have come to know Beth, she quickly became one the models of the kind of feminist mentor and scholar I endeavor to be. But, before I knew her, I was pretty nervous to meet Dr. Schneider when I arrived on campus for my interview. What I later learned was that my initial interactions were sort of classic Beth. While hiring me, Beth also mentored me through the hiring process—with more than a bit of feminist panache. If you don’t know of her or her work, Dr. Beth Schneider is a sociologist of sexualities and gender (in that order, thank you very much). Here, I want to share a bit about her role in helping to produce an identifiable sociology of sexualities and to tell you about the “Beth Schneider Effect.”

Beth has had an unusually influential role in the production of a sociology of sexualities. Her impact affected scholarship in the areas she studied (workplace relationships, harassment, sexual violence, work on HIV/AIDS and AIDS activism, and more). But it also stretched far beyond. Beth is a field builder and has been making space for feminist scholars of and feminist scholarship on sexualities for decades. This is a quality that I’ve started referring to as the “Beth Schneider Effect.”

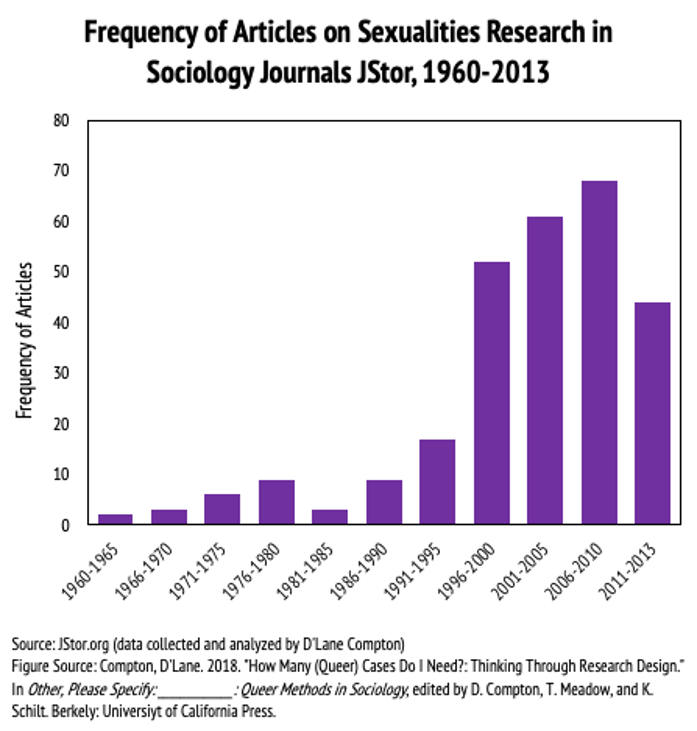

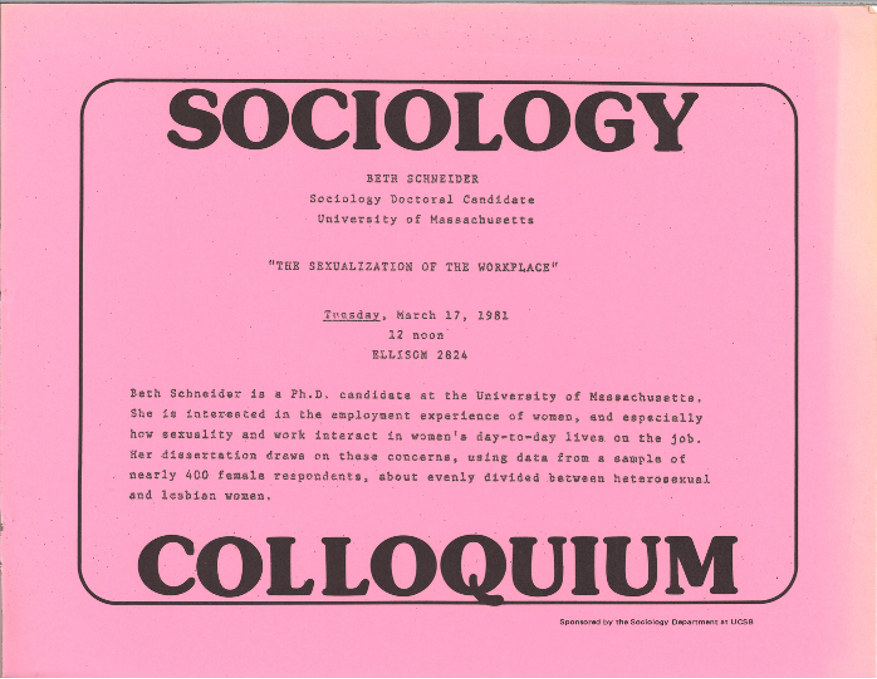

Sociological scholarship addressing sexualities has long existed. But we didn’t always have a section, with members, subspecialties, awards, and more. The figure below is drawn from D’Lane Compton’s archival research in JStor, looking back through published work in sociology journals. Beth received her PhD from the University of Massachusetts in 1981. While she was in graduate school, the numbers of published articles in sociology journals on issues to do with sexualities were small. They were so small that two grad students huddled in a university library could enumerate all of them with their fingers and toes with digits to spare. You can see that the period of growth in the field came after Beth received her PhD. Beth’s early work was ahead of the curve in this respect. And for anyone who knows Beth, this won’t be much of a surprise. Beth’s dissertation research analyzed the sexualization of the workplace, comparing the experiences of heterosexual and lesbian women, focusing on everything from workplace affairs to sexual harassment and assault. It is as timely and important a topic today as when she first completed it. In the project, she found that many women in her study found sexual partners at work. The heterosexual women in her sample were more likely to partner with men who were their superiors while the lesbian women were more likely to end up with women who were their equals. She explained this as a logical outcome in gender stratified workplaces. Among the many aspects of this study that are noteworthy is that the dataset Beth produced included information from almost 300 lesbian women—an impressive sample today, but extraordinary at that time. And studies on lesbians were very rare, particularly in sociology.

Beth’s dissertation research analyzed the sexualization of the workplace, comparing the experiences of heterosexual and lesbian women, focusing on everything from workplace affairs to sexual harassment and assault. It is as timely and important a topic today as when she first completed it. In the project, she found that many women in her study found sexual partners at work. The heterosexual women in her sample were more likely to partner with men who were their superiors while the lesbian women were more likely to end up with women who were their equals. She explained this as a logical outcome in gender stratified workplaces. Among the many aspects of this study that are noteworthy is that the dataset Beth produced included information from almost 300 lesbian women—an impressive sample today, but extraordinary at that time. And studies on lesbians were very rare, particularly in sociology.

In one of her first articles published from this study, Beth reports on her impressive sample of lesbian and heterosexual identifying women with a survey she sent out by mail. In that article, decades before #MeToo, she wasn’t surprised to find that women experienced numerous unwanted physical and sexual experiences at work. But Beth Schneider helped to identify the “recognition problem” wherein fewer women were willing to label the unwanted behavior “sexual harassment.” It’s a problem that continues to be examined today. A key finding in that portion of her research was that lesbian women were more willing than straight women to recognize and label sexual harassment as such.

I know this because I re-read Beth’s scholarship when I nominated her for the Simon and Gagnon Lifetime Achievement Award. But I decided to dive in the deep end after I found a copy of the job talk poster from when she came to our campus as a PhD candidate. Beth gave her job talk at UCSB 16 days before I was born, on March 17, 1981. I mention this specifically because anyone reading this essay who is a scholar among my generation or younger entered this field on very different footing. Or perhaps it would be more accurate to say that we entered this field with an identifiable subfield to stand on in the first place. And a great deal of this is due to feminist scholars of sexualities like Beth. Beth was not alone. Indeed, there is a small group of scholars of her generation who had a Beth Schneider Effect of their own – on slightly different areas and among slightly different communities (with a heavy amount of overlap I’d guess). But here, I want to consider the Beth Schneider Effect Beth has had on the sociology of sexualities.

Beth gave her job talk at UCSB 16 days before I was born, on March 17, 1981. I mention this specifically because anyone reading this essay who is a scholar among my generation or younger entered this field on very different footing. Or perhaps it would be more accurate to say that we entered this field with an identifiable subfield to stand on in the first place. And a great deal of this is due to feminist scholars of sexualities like Beth. Beth was not alone. Indeed, there is a small group of scholars of her generation who had a Beth Schneider Effect of their own – on slightly different areas and among slightly different communities (with a heavy amount of overlap I’d guess). But here, I want to consider the Beth Schneider Effect Beth has had on the sociology of sexualities.

To date, there is little agreement on precisely how to measure a Beth Schneider Effect. We might consider citation records, reprints, article downloads, or presence on course syllabi. And while all of these measure influence, and Beth has notable achievements on each, none of these measures get at what I mean. None of those measures illustrate an individual scholar’s ability to create more seats at the table, or assemble the table in the first place. And it’s precisely that quality of Beth’s work in this field on which I reflect here.

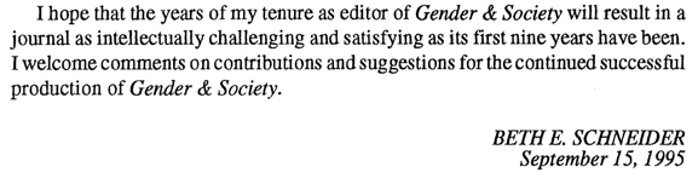

I’m a sociologist, so it’s easiest for me to think through a puzzle like this with a bit of data. And it’s certainly not a random sample of data I’ll present here, but in an attempt to settle scholarly disputes over measuring Beth Schneider Effects that is perhaps in vain, I want to present some data that shapes one of the first ways I came to know Beth Schneider’s name and work. She served as the third Editor of Gender & Society. When I came out to give a job talk at UCSB, I looked back through the issues that came out under her tenure and noted the incredibly influential work published during her tenure. [A note: I realize Gender & Society is not a sexualities journal, but a silly thing like that would never have stopped Beth.] This paragraph above is the conclusion to Beth’s first Editor’s Note. These notes range from 2-3 pages and they offer some insight into some of Beth’s vision for the journal and field. While Beth edited Gender & Society, she published 16 Editor’s Notes. Collectively, they are approximately two Gender & Society article’s worth of text – 15,912 words. I read all of them preparing for a presentation I gave on her work and influence. They’re beautifully written, and if you don’t know Beth, they’re a lovely introduction. Listen to the beginning of her first Editor’s Note:

This paragraph above is the conclusion to Beth’s first Editor’s Note. These notes range from 2-3 pages and they offer some insight into some of Beth’s vision for the journal and field. While Beth edited Gender & Society, she published 16 Editor’s Notes. Collectively, they are approximately two Gender & Society article’s worth of text – 15,912 words. I read all of them preparing for a presentation I gave on her work and influence. They’re beautifully written, and if you don’t know Beth, they’re a lovely introduction. Listen to the beginning of her first Editor’s Note:

“It is mid-September in Santa Barbara, California. A hummingbird is feasting at the Mexican sage, and the watermelon, cantaloupe, and peppers still grow in our garden... This year I am teaching two new courses (“Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual People of Color” and “Feminist Politics and Policy”) and transforming two others (“Lesbian and Gay Communities” and “Contemporary Women’s Movements”). Preparing the materials for these courses has made me hunger for more systematic data collection on the undocumented activities of grassroots and community organizations and more sustained theorizing about the interconnections of the relations of sexuality, gender, race, and class… These courses reflect the complicated intellectual ground on which I currently stand, a conflicted place torn between the problematics and debates in feminist scholarship and those of queer theorizing and lesbian and gay politics. No doubt, some of these concerns will be addressed over the next several years in Gender & Society.” (HERE: 6)

Whether or not that last bit was meant as invitation or mandate, Beth was right. Many of these concerns were addressed over the next several years and continue to provoke scholarship today. And Beth played a crucial role in helping create a home for that scholarship. Indeed, Beth served as Chair of the Sexualities section of the American Sociological Association twice (2001-2002 and again in 2009-2012), was a member of the Editorial Board of Sexualities for a decade of her career, and mentored an impressive collection of feminist scholars who study sexualities and have gone on to have Beth Schneider Effects of their own as well. Her work as Editor of Gender & Society is only one piece of her impressive career. I focus on it here because it helps me to neatly illustrate the point I want to make about how much gratitude we all owe Beth Schneider.

When Beth edited Gender & Society, she encouraged people to call the editorial office at UCSB with questions and concerns in her Editor’s Notes. Can you imagine? Manuscript submissions came in by snail mail to the journal, where they were filed, mailed out to reviewers, mailed back to the editor’s office, reviewed, and sent back by snail mail back to authors. People read the hard copy of the journal, or thumbed through the volumes bound together in university library stacks. Today, Gender & Society dedicates fewer pages to Editor’s Notes. But when Beth was editing and scholars were more apt to read the journal cover to cover, Editor’s Notes helped provide some of the connective tissue out of which “the field” took shape. This provided editors a chance to tell readers about the types of work being submitted, to push scholars to engage with new work and ideas, to reflect on feminist issues of the day, and more. Beth did all of this and more. For instance, Beth encouraged more work on sexualities as well as work pursuing an intersectional perspective. And she deliberated publicly on how to encourage scholars to engage with these ideas. In one Note, she wrote,

“I [am] still… pondering how to encourage authors to take seriously what I believe to be a central feature of feminist sociology: the recognition of the complex relations of race, class, gender, and sexuality and how they shape every study undertaken, no matter what the research subject, methodological approach, or theoretical perspective…. I want to move toward a deliberate consciousness of these relations and processes on the part of our contributors, such that the analyses of their own findings explicitly explore and discuss these potentially challenging implications. As a reminder, no lesbian need be present to consider structure and relations of heterosexuality, and race is present in any study of white women.” (HERE: 365)

Beth consistently pushed scholars to consider sexuality as an integral part of the initial holy trinity of intersectionality: race, class, and gender. And whilst celebrating scholarship coming out in these issues, she also challenged some and pushed scholars to strive for more and called for a feminism that was explicitly and unabashedly anti-racist. In another Note, she wrote:

“Some [authors] are more attentive to the question of how to make sense of the question of these [intersecting] inequalities even in work not intended to tackle this question directly. The embeddedness of class and class relations seems easier to grapple with than race and race relations in most of these contributions, and this pattern generalized over time raises questions for me about how race continues to be taken for granted in research on, and/or by, white women.” (HERE: 679)

Many of these issues and others raised consistently and boldly by Beth are issues that remain in feminist scholarship today. This work helps to provide a sense of some of what I have come to understand as Beth’s mission as Editor, a mission that has guided her work and influence in the field more broadly as well.

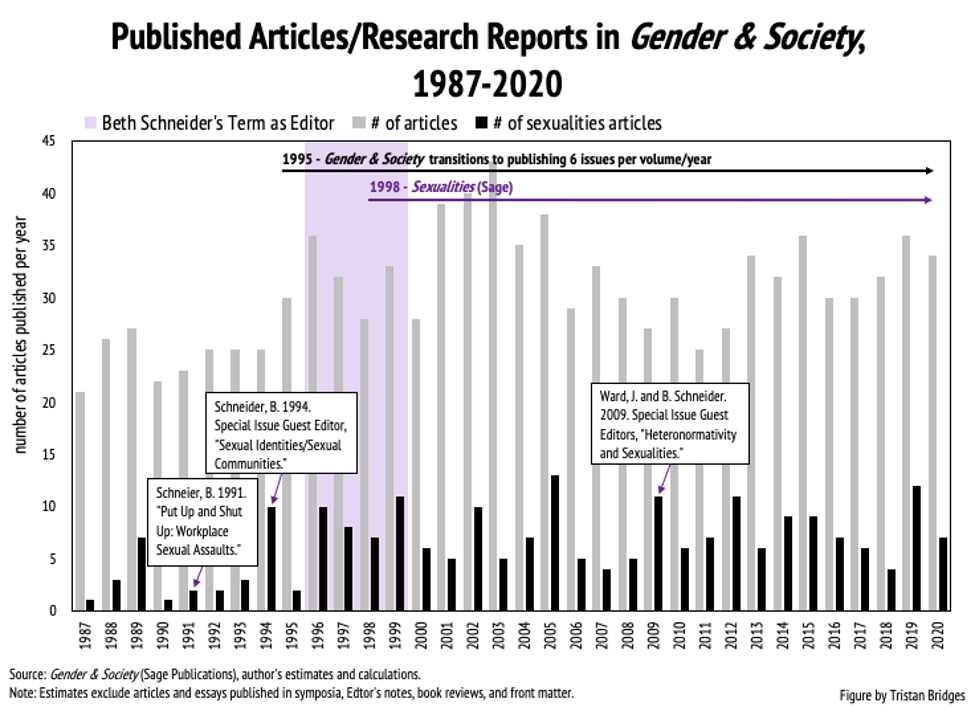

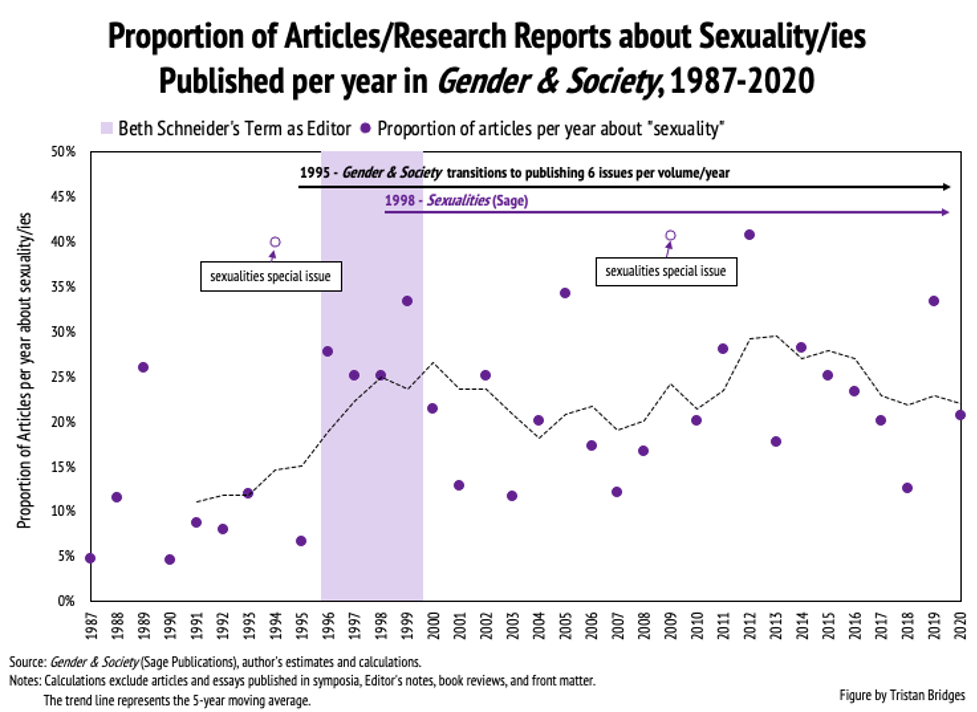

All of this helps me to demonstrate that Beth consistently asked for more sexualities scholarship and wanted that work to be explicitly intersectional. But, to really document a Beth Schneider Effect, we ought to properly document it. To continue using Gender & Society as just one metric, I wanted to see if I could demonstrate some of what I thought might be true. So, I counted and coded all of the articles and research reports published in Gender & Society between the first issue in 1987 and 2020. And I also counted the number of those articles and reports that might legitimately be called “sexualities scholarship” really broadly defined (below). The gray columns illustrate numbers of articles and reports published, and the black columns visualize the number of those articles and reports that are centrally about sexuality/ies. This period shaded in purple illustrates Beth Schneider’s term as Editor. A year prior to Beth taking over, Sage asked Gender & Society to move from 4 issues a year to 6. So, the work of editing the journal increased a bit as the journal provided more space for more work because of the journal’s fast success. Right in the middle of Beth’s editorship, Sage also started publishing Sexualities, an international interdisciplinary journal dedicated to publishing sexualities scholarship.

A year prior to Beth taking over, Sage asked Gender & Society to move from 4 issues a year to 6. So, the work of editing the journal increased a bit as the journal provided more space for more work because of the journal’s fast success. Right in the middle of Beth’s editorship, Sage also started publishing Sexualities, an international interdisciplinary journal dedicated to publishing sexualities scholarship.

In fact, one of the early articles in Gender & Society on sexuality was Beth’s. In 1991, she published her important article in the journal on workplace sexual assault. Prior to her term as Editor, Beth got some early practice guest editing a special issue in 1994 on “Sexual Identities and Communities.” More articles were published in G&S on sexuality that year than any prior because of that special issue. Additionally, about a decade after her term as Editor, having clearly not had enough, Beth and Jane Ward (one of her graduate students who also served as a Managing Editor at Gender & Society while in graduate school) came back to guest edit a second special issue on “heteronormativity and sexualities.” And all of this work created a home for scholarship that has gone on to be incredibly influential.

Those data also give us the information to consider the proportion of work published on sexualities in one journal over time (see below). There is a bit of noise in these data. You can vaguely decipher an upward trend, but year-to-year, the data fluctuate; they’re not perfectly linear. And among the reasons they’re not linear, I’m arguing, is Beth Schneider. And herein lies one small piece of evidence for the Beth Schneider Effect she has had on our field. The trend line on the figure above helps to visualize the bi-modal shape of the trend I’m documenting here. There are two peaks. The first begins when Beth published her first article in Gender & Society, continues to rise with her first guest edited issue, and is sustained during her tenure as Editor. The second appears to have been precipitated directly by Jane Ward and Beth’s subsequent guest editorship and special issue. The work in these articles does not necessarily cite Beth Schneider. It wouldn’t show up on many traditional metrics of scholarly influence. But this is a kind of feminist scholarly influence to which I think more scholars ought to aspire.

The trend line on the figure above helps to visualize the bi-modal shape of the trend I’m documenting here. There are two peaks. The first begins when Beth published her first article in Gender & Society, continues to rise with her first guest edited issue, and is sustained during her tenure as Editor. The second appears to have been precipitated directly by Jane Ward and Beth’s subsequent guest editorship and special issue. The work in these articles does not necessarily cite Beth Schneider. It wouldn’t show up on many traditional metrics of scholarly influence. But this is a kind of feminist scholarly influence to which I think more scholars ought to aspire.

In addition to her many accolades as a scholar, teacher, and mentor, this is what I mean when I say Beth has had a “Beth Schneider Effect” on our field. No matter who you are or what you study, teach, or learn in sociology, if it has to do with sexualities, this woman helped to build an academic subfield big enough for you to find a seat at the table, and scholarly homes in which that work might be better appreciated. Sociology is a better place for having Beth among us.

______________________

NOTE: This essay began as a talk I gave at Beth’s invitation at the American Sociological Association conference in August of 2019 on a panel celebrating Beth Schneider’s work in honor of her receiving the Simon and Gagnon Lifetime Achievement Award from the Sexualities Section of ASA. Since that presentation, I’ve wanted to do something more with this and decided to edit it to share as a public essay celebrating Beth’s work and legacy.

Tristan Bridges is Associate Professor of Sociology at the University of California Santa Barbara.