The journal, Sex Roles, is among the most highly ranked and influential journals publishing research on gender in the world. I recently joined the editorial board and am really honored to evaluate research considered for publication there. This isn’t a post about the content of the journal, though; it’s a post about the title. I want to suggest that we change it. I recognize what a logistical nightmare this would be for the publisher, Springer, and how much work would need to be done to re-brand the journal. But, I also think that some of the most cutting edge scholarship going on in gender might never see the journal as an appropriate venue with a dated title that relies on a concept and pays homage to a theory gender sociologists moved away from over three decades ago.

The journal, Sex Roles, is among the most highly ranked and influential journals publishing research on gender in the world. I recently joined the editorial board and am really honored to evaluate research considered for publication there. This isn’t a post about the content of the journal, though; it’s a post about the title. I want to suggest that we change it. I recognize what a logistical nightmare this would be for the publisher, Springer, and how much work would need to be done to re-brand the journal. But, I also think that some of the most cutting edge scholarship going on in gender might never see the journal as an appropriate venue with a dated title that relies on a concept and pays homage to a theory gender sociologists moved away from over three decades ago.

Sex role theory was the first systematic attempt to theorize gender when sociology was dominated by the paradigm of structural functionalism. But, when we teach undergraduate and graduate students about sex role theory today, we often address the various failings of the theory (and to be clear, there are many). Sex role theory was really the first systematic attempt to tie the structure of gender identities and what others called personality or “sex temperament” to the structure of society. This might sound like a small feat today, because it is so taken for granted as a basic assumption behind so much scholarship motivated by this simple premise. Put another way, sex role theory helped to label something “social” that lacked status as something to be studied by sociologists, at least in the ways sex role theory invited.

Like structural functionalist theory more generally, however, sex role theory was subject to a variety of critiques. In C.J. Pascoe and my introduction in Exploring Masculinities, we summarize four prevalent critiques of sex role theory. The theory is tautological, teleological, ahistorical, and fails to account for gender diversity or inequality–damning critiques, to be sure. I won’t belabor the point. Rather, I’ll put it this way. The first time I submitted something to Gender & Society there was a brief caveat in the manuscript submission guidelines that explicitly stated that work relying on sex role theory was not appropriate for publication in the journal. It’s since been removed–and I’d imagine this was probably done because people no longer submit articles that attempt to use the theory to explain their findings. But it speaks to the level of agreement about the demise of the framework.

The current editor of Sex Roles, Janice Yoder, is fantastic. She wrote a really insightful and inspiring essay in her new role as editor in December of 2015–“Sex Roles: An Up-To-Date Gender Journal With An Outdated Name.” I won’t reiterate all of the great points Yoder addresses there (but you should read them). What I will say is that she addresses the origins of the journal in the 1970s, as an publication desiring to publish scholarship focusing on “sex roles” as opposed to “biological, dimorphic sex”–an important project. At the time, sex role theory was in vogue, and it was a concept and theory that had purchase in a variety of disciplines, likely helping initial editors justify the need for a journal in a still-emerging field of study. The first issue was published in 1975. Other journals emerged around this time as well, like Feminist Studies (1972) and Signs (1975) for instance.

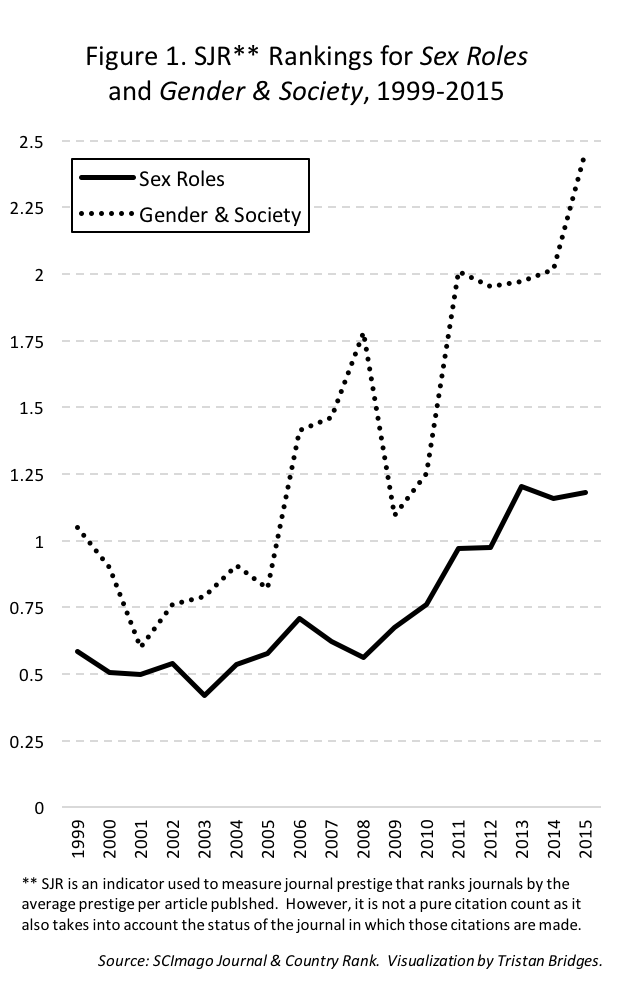

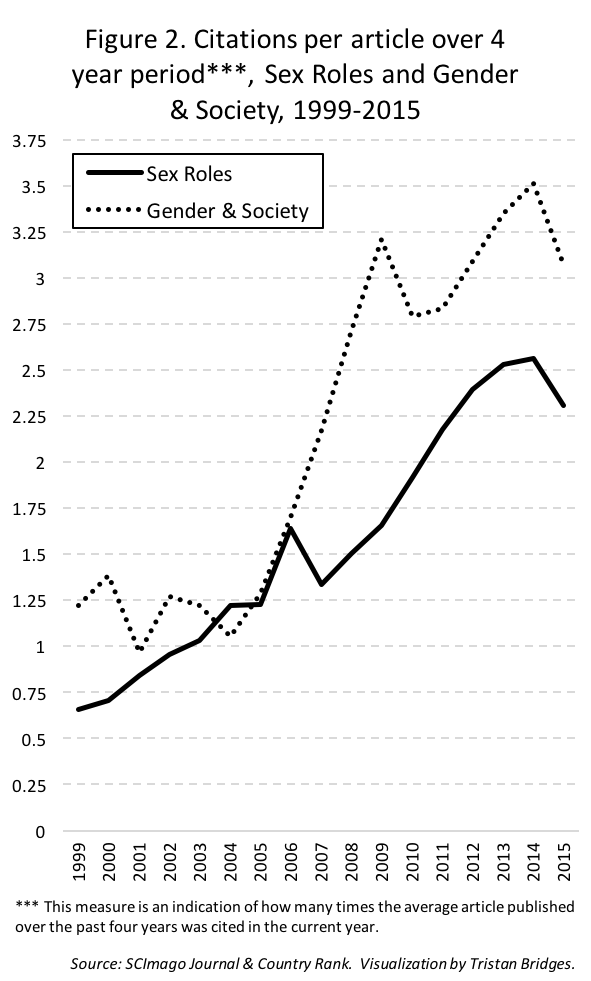

But a separate collections of journals arrived a bit later like Gender & Society (1987), the Journal of Gender Studies (1991), and a whole collection of journals around the world and in different fields of study. Sex Roles has consistently been ranked a top 10 journal publishing gender studies research. Below, I want to compare the journal to the top ranked journal publishing research on gender–currently Gender & Society–to illustrate the impact of Sex Roles. This is helpful to sociologists, I think, because Gender & Society is the gender journal many use to evaluate other gender journals in this field. Gender & Society and Sex Roles are both hugely influential in the field (Figure 1). Both journals have climbed in the rankings recently and have seen their impact grow. Gender & Society is also a journal with a high citation per article count, and articles published in Sex Roles are not far behind (Figure 2).

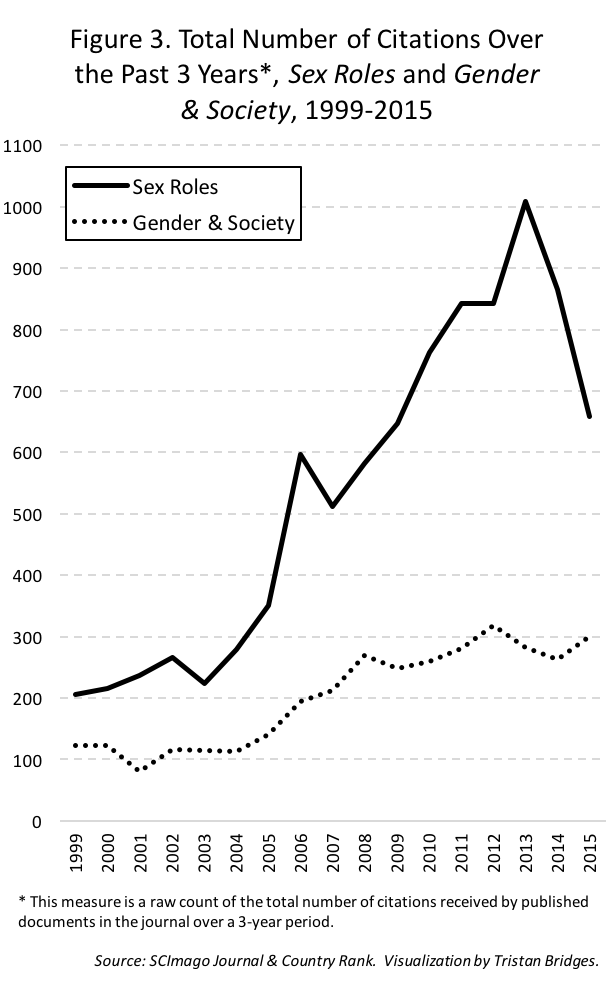

Sex Roles, however, has also been published over a longer period of time and publishes more articles over the course of a year. So, while the average article published in Gender & Society receives more citations than the average article published in Sex Roles, the total number of citations that articles published in Sex Roles receive is roughly 2-3 times the number received by Gender & Society (Figure 3).

All this is to say that there are certainly lots of ways to measure influence. And by all measures, Sex Roles has a lot. It matters–and the research published in Sex Roles ends up in a whole lot more reference sections of books and articles than does the work published in Gender & Society.

I think the journal should change the title. And I realize that I’m not centrally involved in the work that would be required to undertake this task. But, I’d wager that most of the scholars publishing research in that journal would support the critiques leveled against sex role theory in the 1980s by scholars like Barrie Thorne, Judith Stacey, and Raewyn Connell. And I think a larger group of scholars would consider Sex Roles as an outlet for their research with a different title. I realize that the logistics of this are much more complex than simply changing the cover and masthead. It would involve a campaign on the part of Springer, current and former editors, as well as interdisciplinary collaboration among gender researchers.

After considering the change possible, the very first step would likely be to figure out what the new title of the journal might be. My vote would be for “Gender Relations,” a concept that comes out of Raewyn Connell’s theory of gender. Embedded in this concept was a critique of sex role theory and the biological reductionism that Yoder discusses in the essay I mentioned earlier. On top of this, when we look at the mentions of the concept of “sex roles” in Google ngrams, you can see the decline of use over the years from a high point right around 1980. Since then, the concept has fallen out of favor–a shift that coincides neatly with the increasing prevalence of “gender relations” (see below).

As I’ve become more familiar with the journal over the past couple years and enjoy the research published there. I realize that I have little influence and that this blog post is unlikely to initiate this change. But when I’ve discussed this with other sociologists who study gender, I have yet to get into a conversation with someone who doesn’t have a problem with the title. Maybe we can do something about it.

Comments 3

Freeden Oeur — September 1, 2016

Terrific post; thanks, Tristan. I can get behind this campaign! I agree with the analysis and only write to speculate about one possible explanation for why "roles" remains in the journal's title. I'm sure you've already consider this, and I see some of this at work in Yoder's great 2015 piece.

I remember stumbling across Zosuls et al's 2011 review of the history of research in Sex Roles:

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3131694/

I recall being struck by how strange the language and concepts were to me as a sociologist. This isn't at all meant to be a critique of this article or even the journal, but I think I soon concluded (perhaps too hastily) that this particular analysis of gender seemed more the domain of other fields, especially psychology and human development. A clue is in the first line, which speaks to the central theorizing of "socialization" in the journal; by contrast, as you know, one of the most pioneering articles to emerge in the pages of Gender & Society (which seems more of the go-to journal for sociologists and the like), and which even appeared in Gender & Society's first volume (and therefore helped to inaugurate a particular stream of gender theorizing), is West and Zimmerman's "Doing Gender," which explicitly challenges the notions of roles and socialization. More digging into the 2011 piece reveals concepts (e.g. stereotyping), models (e.g. Bem's), and people (e.g. Kohlberg) that just don't seem central anymore for sociologists. I suspect a search for these and other important concepts in Zosul's review piece would yield far lower returns in Gender & Society.

So it seems that the divergent trajectories of Sex Roles and Gender & Society have been driven by different groups of disciplines. (And it seems that Sex Roles puts out a higher volume of work because the journal draws on researchers from a wider range of disciplines than Gender & Society?)

The Zosuls et al. piece is authored by psychology and human development researchers (imagine the same kind of review piece written in Gender & Society; I'd wager that more than one of these authors would be sociologists), and perhaps those working in these traditions are more amenable to using (and defending) "roles" and the like and find a certain usefulness in them that sociologists don't see? I don't, for the important reasons you explain above. I just wonder if the point of view we share as sociologists would be interpreted by scholars in other fields as "those sociologists" wanting to create a Gender & Society 2.0... when perhaps it's important to maintain two distinct journals catering to two sets of disciplinary traditions... and with two very different names? If indeed sociology has taught us not to be ahistorical, then promoting a name would mean trying to change the course of history in a way. The last graph is really helpful in demonstrating that the use of "sex roles" has declined, but there could be a lurking story of other sex-role-like terms that continue to thrive and inspire researchers across a range of fields... and could even benefit the work of sociologists.

I'm all for more interdisciplinary work, but I conclude by asking if there's a benefit to keeping Sex Roles (with that name or a new one) and Gender & Society as distinct journals that cater to different research audiences. And if nothing else, for those of us who are more inclined to pick up an issue of Gender & Society than a copy of Sex Roles, perhaps this is time for some self-reflection. We should ask if suggesting a name change in Sex Roles implies that the journal should "look more like" Gender & Society. Perhaps yes, but that likely suggests that a long and rich history of research in Sex Roles needs to play a game of catch up of sorts. Is it the case (as Yoder implies) that the journal's name is out of date when the field has accelerated ahead; or is it the case that the name "sex roles" continues to reflect important questions and debates for non-sociological gender scholars?