Most of us here at Feminist Reflections (FR) just got back from attending the 2015 Winter Meetings for Sociologists for Women in Society in blustery Washington, D.C. Trina Smith organized a panel presentation on the founding of Feminist Reflections as “a space for feminist public sociology.”

We ended up with a time slot during the 3:30 – 4:30pm coffee break instead of our planned 2pm slot and, also without our knowledge, our panel was shortened from 90 to 60 minutes. Luckily, our small conference room was packed. We sped up our presentations to leave time for what was really an invigorating conversation. Thanks to all of you who gave up your coffee break to join us and participated in the Q&A.

We wanted to take this chance to reproduce some of our SWS panel for you here on FR. We started with some history and then moved on to why we blog, and why specifically we blog here.

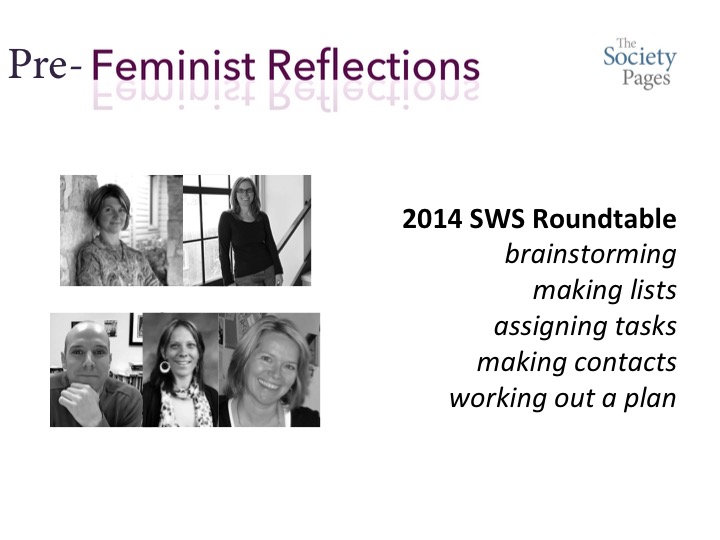

Feminist Reflections was borne out of a discussion at the 2014 SWS Winter Meeting one year ago in Nashville. Gayle Sulik and Meika Loe invited Tristan Bridges to participate in a roundtable discussion on blogging and the lack of a digital feminist platform for public sociology. Amy Blackstone and Trina Smith were two of the attendees to this small group discussion, and over the hour that our conversation took shape, we came up with the idea of collaborating and potentially working with The Society Pages (TSP).

It took 5 months to get our ideas together, set up a plan, come up with a blog name that reflected our mission, and work with the incredible team at TSP to transform our idea into a reality. All of a sudden Feminist Reflections was real.

It took 5 months to get our ideas together, set up a plan, come up with a blog name that reflected our mission, and work with the incredible team at TSP to transform our idea into a reality. All of a sudden Feminist Reflections was real.

FR has been live for just over 6 months. We’ve had more than 75 posts, 5 amazing guest contributors, and we’re thrilled that one of our guest contributors, Mindy Fried, will be the newest member of our editorial board!

After this brief history, we [Gayle, Amy, Trina, Tristan, and Mindy] each presented on various reasons for blogging.

Gayle talked about blogging as a labor of love (emphasis on both the love and labor). But through blogging, Gayle has found extraordinary opportunities for collaboration, a professional platform, and access to audiences who, though they may benefit from feminist sociology, are not inclined to read the articles or books we most often use to share our insights and findings.

Amy shared how blogging led to greater public visibility, allowing her to help shape a national conversation about making the choice to be childfree. She also discussed the support, community, and fun that comes from joining a collaborative feminist sociological blog.

Amy shared how blogging led to greater public visibility, allowing her to help shape a national conversation about making the choice to be childfree. She also discussed the support, community, and fun that comes from joining a collaborative feminist sociological blog.

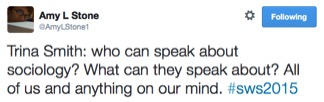

Trina shared her experience of moving to the rural South and thinking about sociology as a coping mechanism to help process some of the struggles associated with that. She also asked us to consider important questions about power and knowledge—“Who can speak about sociology?” and “What can they speak about?” Amy Stone summed up Trina’s important answer: Tristan talked about using blogging as a way of injecting more nuance into conversations going on in the media related to his research. He also discussed the importance of blogging as establishing a new feminist network of support and engagement after leaving graduate school.

Tristan talked about using blogging as a way of injecting more nuance into conversations going on in the media related to his research. He also discussed the importance of blogging as establishing a new feminist network of support and engagement after leaving graduate school.

Mindy concluded our panel with an important discussion of the blurred lines between personal and professional that blogging sometimes allows. Like Gayle, she also addressed the power of collaboration through blogging in addition to some of the ways she uses blogging in teaching, applied work, and to make sense of feminist sociological triumphs and struggles.

After our panel, we had a chance to meet up the next day in person again to talk about future directions for the blog. As Gayle put it in her opening presentation at the panel,

“Feminist Reflections is a room of our own. Even better, there’s room in this room.”

We are committed to sharing this space with others interested in using feminist sociological lenses to reflect on issues important to them. And we’re open to these taking on a variety of forms: discussions of teaching practices, personal experiences, emerging research problems and findings, and more. We are excited to share the feminist reflections of others and are in the process of developing formal guidelines for guest contributors. Please consider Feminist Reflections as a potential outlet and platform for sharing your voice.