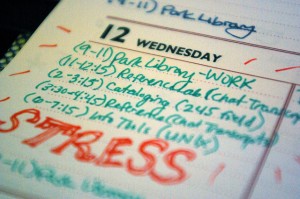

Everybody loves to talk about stress—including work/family aka work/life balance stress. But it is a tricky topic that can bring casual listeners to the conclusion that something like stress—that is experienced as personally as enhanced heart rates or elevated cortisol levels—must require personal solutions. Sociology points in another direction.

To wit, recently the Council on Contemporary Families shared a briefing report from Penn State sociologist Sarah Damaske about research she and colleagues conducted that showed that working people have higher cortisol levels at home than at work. Though stress is experienced in the body, it is ultimately about context, about policy, not about individual character or family-values sentimentality.

Damaske explained her results,

When my fellow Penn State researchers, Joshua Smyth, Matthew Zawadzki, and I measured people’s cortisol levels, a major biological marker of stress, we found that people have significantly lower levels of stress at work than at home. These low levels of cortisol may help explain a long-standing finding that has always been hard to reconcile with the idea that work is a major source of stress: People who work have better mental and physical health than their non-working peers, according to research published in the Journal of Health and Social Behavior, Social Science Research, the American Sociological Review, and the Handbook of the Sociology of Mental Health.

Damaske’s work, and our CCF brief, has already covered amply by national media (like this video), and here, and here, and here.

Damaske made a smart recommendation in her brief in favor of flexible workplaces as a way to diminish stress. But why is this about the work place when the stress is higher at home? It could be that at work what counts as success or even the beginning or end of a project may be clearer. At the same time, the expectations at work is that you give your “all” to work, spend many hours there, and be at the ready in a crisis. I discussed this with Lois Collins at Deseret News: With a flexible workplace, people are no longer put in the position to “fail” at home in order to succeed at work. To read more about ROWE (results oriented work environment–a program Damaske discussed in her report), read this profile of a Gender & Society study on a flexible workplace program that illustrates how it works and see a new American Sociological Review study by Erin Kelly and colleagues on it as well.

Damaske’s research is important because it refocuses us from the fantasy that just won’t die that market work and domestic work are done by different individuals who occupy different roles. That has hardly ever been the case, but when people are surprised by Damaske’s study results it is often because of the backdrop of believing that “home is a haven” is true. Home and work are key venues where we seek to stabilize our existence and when lucky make the world a little better.

When patterns like seeing that people have higher stress at home than at work are identified, it suggests that policies as well as attitudes can make our lives easier or harder. Along with flexible workplaces and “good jobs” with good worker protection, I also encourage looking out for hidden forms of nostalgia for home. Without cultural standards that idealize “home” and leave you feeling terrible when you just can’t measure up in all the domains where you work, stress can look like it is about you. But stress, Damaske’s paper shows us, is not about you.

Comments