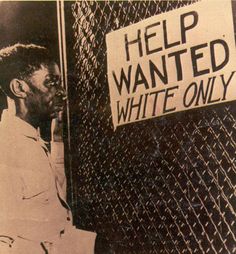

The relationships students form with their guidance counselors impact their college-application success. For even the most-prepared high schoolers, applying for college can be daunting. For some minority, low-income, and first-generation students, it can seem like an insurmountable obstacle to college. That’s why when parents lack concrete information despite being eager to help, students often turn to counselors to walk them through the process.

To better understand how trusting relationships are created, Megan Holland interviewed 89 students and 22 school counselors at two racially and socioeconomically diverse high schools with high graduation rates. She spent two years observing the schools and attending their college fairs, parents’ nights, and financial aid nights. At both schools, counselors struggled to meet the demands of two very different groups: “the wealthy, high-powered student population who attend highly selective colleges” and “the lower-income population struggling to graduate.”

Holland found that trust was developed through shared understandings of expectations and roles. More-advantaged students, prepared by their parents, tended to come in on the same page as their counselors. In contrast, less-advantaged students tended to struggle more with the application process and were often mistaken as lacking effort or motivation. Holland shows that this misunderstanding may occur because some counselors, though they worked to provide more information, didn’t necessarily recognize when students needed help accessing and using it.

Some counselors were more successful in establishing trust with less-advantaged students, and they suggest strategies for improving this group’s access to college information. These counselors were more proactive in seeking out students who missed deadlines, they made a point of clearly communicating their expectations, and they demonstrated personal regard for students by supporting their goals.

You can read the full article here:

Megan M. Holland. (2015). Trusting Each Other: Student-Counselor Relationships in Diverse High Schools. Sociology of Education, 88(3), 244-262.

Amy August is a graduate student in Sociology at the University of Minnesota who studies education, parenting and childhood, sports, and competition.