I very recently finished my service as editor of Sociology of Education(SOE)¹—the global flagship journal of this subfield, one of the best journals in both sociology and education research. In that capacity, I read nearly 800 of your new and revised manuscripts—roughly one every weekday for three years—but had room to accept for publication only about 50 them.

I very recently finished my service as editor of Sociology of Education(SOE)¹—the global flagship journal of this subfield, one of the best journals in both sociology and education research. In that capacity, I read nearly 800 of your new and revised manuscripts—roughly one every weekday for three years—but had room to accept for publication only about 50 them.

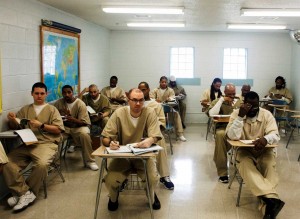

Eric Grodsky asked me to share with you my sense of the subfield after reading all of those manuscripts. I am going to give you my honest assessment because I care deeply about education research. I believe that as a subfield we are capable of making meaningful contributions to the scientific understanding of what education is, how it works, for whom it works and for whom it does not work, and what our society can do to improve it.

In short, I do not believe we are living up to our collective potential.

When I started as editor, I worried that the biggest challenge would be this: How will I choose from among all the great submissions? How will I select just the four or five best articles to publish in each quarterly issue? That worry was based on my sense that a high percentage of submissions would be—or could, with modest revision, become—publishable.

In fact, I consistently had exactly the opposite problem. For each of the 12 issues I published, I struggled to find four high-quality publishable manuscripts. During my first year as editor, SOE had an extra page allocation from ASA²; I did not fill all the extra pages because there were not enough acceptable papers. In all three years, I pressed authors to write more concisely so that I could fit a fifth article in each issue; only once did I succeed in finding five publishable papers³. I am very proud of the articles that appeared in SOE during my three years as editor—and of their topical, methodological, and theoretical diversity—but I leave the journal deeply dismayed at the state of the subfield. I am somewhat dismayed that there were so few high-quality papers. I am more dismayed that there were so many lesser-quality ones.

Most of the papers that I read had one or both of two basic problems:

First, a large percentage of papers had fundamental research design flaws. Basic methodological problems—of the sort that ought to earn a graduate student a B- in their first-year research methods course—were fairly common4. (More surprising to me, by the way, was how frequently reviewers seemed not to notice such problems.) I’m not talking here about trivial errors or minor weaknesses in research designs; no research is perfect. I’m talking about problems that undermined the author’s basic conclusions. Some of these problems were fixable, but many were not.

Second, and more surprising to me: Most papers simply lacked a soul—a compelling and well-articulated reason to exist. The world (including the world of education) faces an extraordinary number of problems, challenges, dilemmas, and even mysteries. Yet most papers failed to make a good case for why they were necessary. Many analyses were not well motivated or informed by existing theory, evidence, or debates. Many authors took for granted that readers would see the importance of their chosen topic, and failed to connect their work to related issues, ideas, or discussions. Over and over again, I kept asking myself (and reviewers also often asked): So what?

I gradually came to understand that (1) many authors just hadn’t yet fully thought through the “so what?” questions and (2) many authors were submitting papers long before they had fully worked through crucial issues related to research design, quality of evidence, and coherence of argument. They didn’t do a great job of motivating their questions because they weren’t yet fully sure how their work fit in the larger scheme of things. They hadn’t thought through the “so what?” of their findings because they hadn’t had time to fully make sense of them. They made assumptions or mistakes in their research design and analyses—just like everyone does in the early iterations of a project and paper—but they submitted their papers anyway.

I think there are two related explanations for why the vast majority of SOE submissions over the past three years were simply not all that great and did not live up to their potential. First, junior scholars are under far too much pressure to quickly publish lots and lots of papers. The problem is that it takes time and thought and trial and error to generate a really compelling research question and to deeply understand how to articulate the importance of that question. Then, it takes more time and thought and trial and error to come to a really convincing answer to that question, to fully develop the argument or story, and to write a manuscript that does justice to the value of the research. Unfortunately, junior scholars do not have enough time or enough room to think or make missteps. Graduate students must publish frequently—while still in graduate school—to complete for fellowships and professional jobs. Assistant professors must publish early and often to get tenure; associate professors must do the same to “make full.” In each case, the pressure is to work quickly and efficiently. They have to get papers out for review as soon as possible, even if they really haven’t had the time to think them through or sharpen their argument or evidence. Quantity matters most, not quality. The incentive is to publish a dozen “just OK” papers rather than to publish four or five well-developed and higher-quality papers. The collective result for the subfield: a mass of underdeveloped papers that often have some potential but really aren’t acceptable for publication in high-quality journals5. These are papers that exist for the sake of being papers because the author is under pressure to write lots of papers. I sincerely empathize with those authors—I once was one, and I socialize and work closely with many of them. Senior scholars in the subfield bear the responsibility for this state of affairs; they are in a position to change it.There simply has to be a better way to run a profession.

Second, junior scholars are not as well trained, mentored, or supported as they need to be. Partly, this goes back to the pressures to publish early and often. But partly, this is the collective fault of graduate training programs and junior faculty mentoring programs (and thus, again, of the senior scholars who lead those programs). Collectively, we simply need to do a better job of training, mentoring, and supporting junior scholars. Standards and expectations need to be higher, but junior scholars need to be given the resources—including time and mentoring—required to meet them. The subfield needs to be more innovative and energetic in designing creative ways to improve training and scholarship.

The modal SOE submission during my three years as editor was written by a junior scholar, had non-trivial methodological problems, and lacked a compelling theoretical or substantive rationale for having been written. This is despite the fact that the authors were well-intentioned, were extremely bright, and worked hard at their craft. Virtually every paper had some kernel of real potential in one way or another—some creative idea, some new insight, some thoughtful new approach—but far too often that potential was not realized. All of this represents, to my mind, a waste of resources—including authors’ time and energy and frequently tax-payers’ money. And, it doesn’t help any of us move closer to addressing the problems, challenges, dilemmas, and mysteries that we all face in education and our broader society.

Nobody asked for my views on how to fix these problems, but here they are anyway. First, sociology departments, education schools and their kin need to de-emphasize thequantity of published papers in making hiring and promotion decisions. Second, those units and fields need to primarily reward the quality of publications. Third, we all need to be more energetic, more creative, and more collective-minded in training, mentoring, and supporting junior scholars. To be clear: The onus of implementing these badly-needed changes falls on senior scholars. Junior scholars are appropriately and understandably focused on their own careers. It falls on senior scholars to transform incentive structures—rewarding quality over quantity—and to provide junior scholars with the time and support they need to do better research and write better papers.

ENDNOTES

1 Although my name is on the masthead as editor for the rest of 2016, incoming editor Linda Renzulli took over the day-to-day operations of the journal on July 1.

2 That’s right: In the 21st century ASA still thinks in terms of printed page allocations and mailing costs.

3 One possibility is that I was too harsh a judge of submissions. Maybe, but: About one in seven authors of new submissions was invited to revise and resubmit their manuscripts, most revised papers were subsequently accepted for publication, and I did ultimately publish at least four papers per issue.

4 The most common questions I wished authors had asked themselves before they submitted their papers included: Is this the best group of people to study in order to achieve my research objectives? How should I measure key concepts, and what are the relative strengths and weaknesses of those measures? Does the evidence I have presented speak directly to my questions or hypotheses? Does that evidence adequately support my arguments, claims, and conclusions? Am I making causal claims, and if I so does my evidence support such claims? If I am comparing multiple groups, have I actually compared those groups?

5 This is not to say that as editor I expected papers to be acceptable and publishable right out of the starting gate. I invited the authors of about 13% of new manuscripts to revise and resubmit their papers based on reviewers’ and my own comments. I know that a big part of the job of a journal editor is to identify promising papers and help them become higher-quality published articles. Like I said, I’m very proud of the papers I published.

[This article is reposted with permission from Rob Warren’s blog.]