Abortion, sex, and marriage. Not my topics of choice, at least not professionally or publicly. Yet with the anniversary of Roe v. Wade upon us, there’s a lot of interesting talk about them lately, especially the former. One of the most thought-provoking pieces I’ve seen was published recently on Slate. It says the rise of single motherhood–40% of children are now born to women who are not married–is a byproduct of the antiabortion movement.

The argument, which comes from law professors Naomi Cahn and June Carbone, is a bit more complicated than you might think, because it doesn’t hold for everyone all across the board. For example, it doesn’t apply for richer, older, and more educated women whose willingness to “accept abortion” has actually helped “create more stable families,” because these women delay childbearing until the right man comes along or they get comfortable with going it alone. Rather, it is focused mainly on younger, less privileged women. Basically, the argument is that the hardening of anti-abortion attitudes has led adult parents, especially Christian conservatives, to become more accepting of their daughters having children, even out of wedlock. Indeed, many of these families apparently reference their Christianity explicitly. This is what Cahn and Carbone call the “Bristol Palin Effect,” and it grabs headlines. The implication seems to be that these young women and their parents are “choosing” a principled anti-abortion stance over traditional family values.

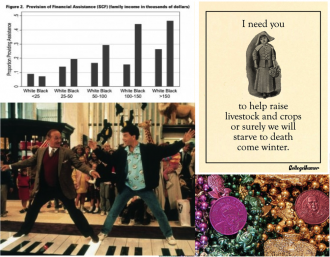

I don’t know how good Cahn and Carbone’s numbers are (they do cite several sociologists), or even if their analysis is really borne out by the empirical data on all of the other factors that obviously contribute to the rise of the “non-marital birth rate” (the welfare state, moral decay, increasing independence of women, etc.). The implied ironies, though, are delicious: not only has the anti-abortion movement made conservatives more accepting of single motherhood, it has made liberals more likely to embrace the more traditional, two-parent family model. Cahn and Carbone, who have a book coming out from Oxford University Press, talk about it as the difference between “red” families and “blue families” (that’s the title of their forthcoming book, actually). Only in America.

This brings me back to changing attitudes about sex, sexuality, and premarital sex–are our views of sexuality more open? Is premarital sex more accepted or simply more taken for granted now? I also think of the curious new coalitions that seem to be emerging with the push for gay marriage recognition and legalization (on this score, see: http://www.nytimes.com/2013/01/30/us/in-shift-blankenhorn-forges-a-pro-marriage-coalition-for-all.html?hp&_r=0). And how does gender play into the picture? I guess it seems to me that this new “approach” lets the fathers of these soon-to-be-born babies, pretty much off the hook, and I’m not sure that’s such a good thing. I’m not really pushing for shotgun weddings, but at least they were based in a recognition of the complicity of a partner and didn’t just leave young moms on their own. Perhaps that’s a little strong, though to be honest, I’m not sure if it is because I’m being too much of a liberal or too much of a conservative in thinking such thoughts.

Read Widely

Read Widely