Read Widely

Read Widely

In case it’s hard to tell, that’s an imperative, not a descriptor. Today I plan to use my little soapbox to trumpet some fabulous writing, while also seeking submissions to what I lovingly call “Letta’s List.”

See, many authors ask me for examples of how to incorporate a lot of information into something that’s thorough, academically sound, and engaging. It’s a tough balance, to be sure, but over the years, I’ve collected a number of books (and this is by no means a list of all of them) I can hand off as representations of that ideal. They likely have nothing to do with your area of study, but watching the authors’ deft hands at work (and knowing there are surely unsung editor elves in there, too) can be a truly enjoyable homework assignment. Think of it as authorial excellence by osmosis. Absorb and emulate.

And then, leave me your list of rockin’ non-fiction in the comments, because Letta’s List is in no way complete. I want it to grow longer every year (which isn’t to say this isn’t already long; skip it if you just want the roundup!). Links go to the presses’ sites wherever possible. Note to those authors and presses prepping to send me book copies: please send paperbacks! Also: thank you.

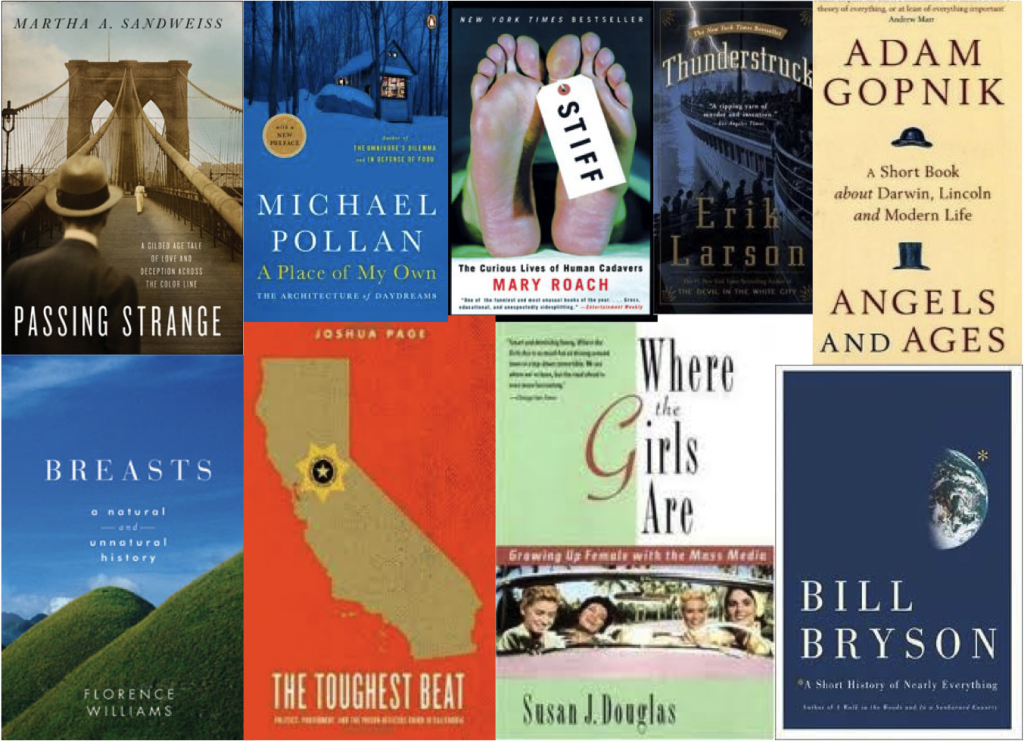

- Martha A. Sandweiss. 2009 (paperback out in 2010). Passing Strange: A Gilded Age Tale of Love and Deception Across the Color Line. Penguin. Sandweiss usess demography, history, and Census data to trace a prominent man’s journey back and forth from the worlds of white luminaries (he was the playboy head of the National Geographic Survey) and black Pullman Porters (in which he was a simple man with a wife, kids, and a job that required a lot of travel). It’s a fascinating true tale that reveals the permeability of 19th and 20th century color lines.

- Mary Roach. 2004. Stiff: The Curious Lives of Human Cadavers. W.W. Norton. Roach has a particularly well-honed touch with science, and is the author of other notable Norton books Packing for Mars, Gulp, Bonk, and Spook. Each is packed with information you didn’t know you craved, but here you are, gobbling up the details of what cadavers have done for you lately, just how astronaut food is developed, and why it’s hard to describe tastes. Stiff is an excellent introduction into her excellent catalog, packed with participant-observation, rigorous research, in-depth interviews, and no shortage of good humor.

- Adam Gopnik. 2010. Angels and Ages: A Short Book about Darwin, Lincoln, and Modern Life. Vintage/Knopf Doubleday. I like to think of Gopnik as the master of final sentences. He can close a paragraph, a chapter, or a book like no other. Doing it in the service of a parallel tale of Lincoln and Darwin, two surprising contemporaries, Gopnik shines. He gives us history, law, theology, and sociology and brilliantly renders a time of modern upheaval, in war and words.

- Steven Johnson. 2007 (reprint edition). The Ghost Map: The Story of London’s Most Terrifying Epidemic—and How It Changed Cities, Science, and the Modern World. Riverhead Trade. Epidemiology, sociology, and mapping shouldn’t make for a gripping tale with life and death consequences, but that’s the talent of Steven Johnson. He traces the sleuths who mapped and interviewed and walked their way through London in search of a killer disease and finally put an end to a public health nightmare, and every bit of it feels vital.

- Bill Bryson. 2003. A Short History of Nearly Everything. Random House. Bill Bryson could—and should—write the phonebook and make it into a hilarious, informative page-turner. His romp across Australia (and through its flora, fauna, and fascinating history), In a Sunburned Country, passes out of my hands with astonishing rapidity, but it’s A Short History that most highlights Bryson’s talent with insurmountable tasks. He explains scientific progress (and the unsung scientists who move it forward) with care and humor and a brisk pace that’s nearly alarming. His At Home is another classic packed with millennia of culture and human behavior, but I’d happily point anyone to any one of his books. Random House: do whatever you can to keep Bryson on your roster. I suggest Scrooge-McDuck-piles of money.

- Susan J. Douglas. 1994. Where the Girls Are: Growing Up Female with the Mass Media. Three Rivers Press. A professor of communications, Douglas used her first book (named one of the year’s top ten by NPR in 1994) to take seriously all that pop culture others at the time were ignoring. ’50s girl groups, Gidget, vacuum cleaner ads, and beehives weren’t, in her view, the things that kept feminism at bay, they formed the incubator from which a new generation of feminism and social change would arise. Or: why shimmying to “Will He Still Love Me Tomorrow?” was—and remains—a feminist act.

- Erik Larson. 2006. Thunderstruck. Broadway Crown Trade Group. A totally spellbinding book about the development of wireless telegraphy? That’s a tall order, but with Larson’s trademark ability to weave two stories together (in this case, the race to establish overseas telegraphy and to solve a London murder), Larson creates a coup. It’s a potboiler with morse code—even if you try to read it just for the sensationalist murder details, you’ll find yourself taking sides in scientific debate.

- Florence Williams. 2012. Breasts: A Natural and Unnatural History. W.W. Norton. This book left me like a teenager: both fascinated by and terrified of breasts. In fact, the science surrounding this functional, titillating, contentious body part left me so utterly freaked out I forced myself to stop reading the book, out of the very real knowledge that continuing might lead me down a certain paranoid path wherein I could no longer look at paint or hold a water bottle. Williams is incredibly talented and I can’t wait to see what she takes on next. Also: the book may be worth the price of purchase for the aforementioned Mary Roach’s back-cover blurb alone.

- Joshua Page. 2011. “The Toughest Beat”: Politics, Punishment, and the Prison Officers’ Union in California. Oxford University Press. Full disclosure: not only am I married to the author of this book, I edited every word of it—and there are probably still typos lurking within. The reason I want it on this list, though, is not simply out of affection or pride, it’s because the author is a true demonstration of how to be edited in the service of a great book. That is, he cares more about the finished product than the first draft. And that finished product has won awards and created comment among policy makers, union leaders, lay readers, and even one of Rolling Stone’s Top 100 guitar players. It’s worth checking out.

- Michael Pollan. 2008 (reprint edition). A Place of My Own: The Architecture of Daydreams. Penguin Books. [Originally published in 1998 as A Place of My Own: The Education of an Amateur Builder by Dell.] Some books have seasons, and I return to this one every spring. Yes, Pollan’s much better known for his screeds on food—the history of it, the best ways to source it, the best way to eat it—but this elegant little book explores the traditions of culture, architecture, and the act of writing, letting readers dabble with shipbuilding and concrete construction, feng shui and barn-raising right along with him. The book itself is a dream made sturdy.

What, you ask, have we been doing on The Society Pages this week? Well, I can tell you that, too. Again, though, let me urge you to share your best examples of gripping non-fiction, especially those books that share science (social or otherwise) in a publicly engaging way, in the comments.** I need to add to the list!

Features:

“A Social Welfare Critique of Crime Control,” by Richard Rosenfeld and Steven F. Messner. In which we learn about managing criminal motivations and opportunities and how we might be able to get to a crime-free society, but it may not be worth it.

Citings & Sightings:

“Service with a Smile—Or Else,” by Evan Stewart. In which Hochschild’s notion of “emotional labor” is employed among employees.

A Few from the Community Pages:

- Sociological Images. A whole month of Soc Images goodness in one place? YES PLS.

- Cyborgology. While the crew readies itself for #TtW13, they also found the time to think over how fiction handles technology and survey (not precisely review) Liquid Surveillance.

- A Backstage Sociologist. Monte, the medical miracle, ponders standup sociology. And, to my personal delight, loved last week’s Roundup.

- Public Criminology. Charis Kubrin on PBS: we’re in. All your sociology are belong to us.

- Sociology Lens. Continues a series on the body: fascinations, representations, ideals, and society.

- ThickCulture. Jose Marichal, haunted and taunted by Adam Smith.

Scholars Strategy Network:

“Migrant Health in the Debate about Immigration Reform,” by Micah Gell Redman. Citizenship has very little to do with the public health risks and benefits of each additional member of “the herd.” Why the U.S. should be paying attention to everyone‘s health.

“What the Proliferation of Recognized Mental Disorders Means for American Healthcare,” by Owen Whooley. With the DSM V, “Disruptive Mood Dysregulation Disorder” is now a thing. Asperger’s Syndrome is not. What gives?

**P.S. Please, please add your favorites in the comments? No comments=lonely editor.

Comments 8

Letta Page — March 1, 2013

I immediately regretted not adding "The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks," by Rebecca Skloot! Amazing reporting, from the science of the era to the politics of race, renumeration, and regret.

http://rebeccaskloot.com/the-immortal-life/

Rebecca — March 1, 2013

LOVE Bill Bryson and Mary Roach. I'd like to recommend anything by Nicole Rafter, especially "Partial Justice" and "The Criminal Brain." I recently read and loved Dave Quammen's "Spillover", which is about the epidemiology of zoonotic diseases, and now I'm reading "Infections and Inequalities" by Paul Farmer.

syed — March 1, 2013

there was a really cool book about dubai a couple of years ago... i forget who wrote it. me?

Pete — March 1, 2013

"Plutocrats:The Rise if the Global Super Rich and the Fall of Everyone Else" by Chrystia Freeland and Joseph Stieglitz "The Price of Inequality" are my two most recent NF reads

The first probably more entertaining the second more academic

Letta Page — March 1, 2013

One more Bryson book I should have pointed out is his endearing little tome Bill Bryson's Dictionary of Troublesome Words: A Writer's Guide to Getting it Right. It remains desk-side, stacked with my many various style guides, the Oxford American Writer's Thesaurus, and a stack of random magazines.

http://www.amazon.com/Brysons-Dictionary-Troublesome-Words-Writers/dp/0767910435