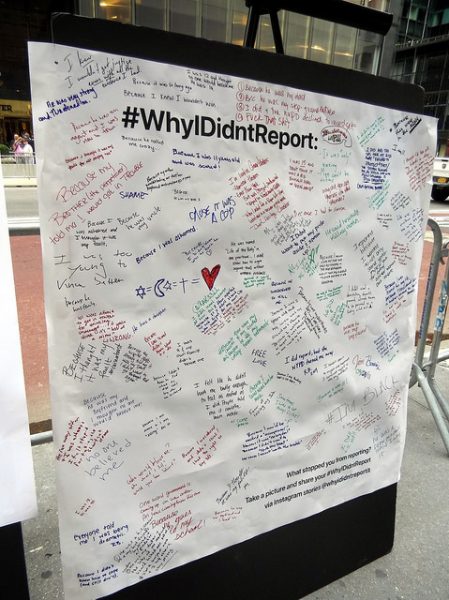

Emotions ran high across the nation as many of us tuned in to watch Dr. Christine Blasey Ford’s testimony of sexual assault by Judge Brett Kavanugh in front of the Senate Judiciary Committee. Dr. Ford’s public testimony has produced important dialogues regarding why most victims do not report, as seen in the social media hashtag #WhyIDidntReport. New research by Shamus Khan, Jennifer Hirsch, Alexander Wamboldt, and Claude A. Mellins contributes to this growing conversation by exploring the social risks students face in reporting.

Khan and colleagues draw upon the Sexual Health Initiative to Foster Transformation (SHIFT) study, which includes 151 interviews, 17 focus groups, 18 months of participant observation, and a random-sample survey of 1,671 college students at Columbia University and Barnard College (a women’s only institution). This study mostly draws from the interviews with college students. Researchers defined incidents of sexual victimization based on legal definitions of sexual assault, rather than incidents that students explicitly labeled as such. According to the authors’ definition, interviews revealed that 66 students recounted 89 incidents of sexual victimization.

For many victims, naming their experiences as sexual assault and telling authorities came with a variety of social risks. For one, students feared association with a stigmatized identity such as “victim” or “survivor.” They often viewed these labels as disempowering and told interviewers they didn’t want to be seen as “that girl” or “that guy.” Some students attempted to claim alternative identities as compassionate students willing to provide second chances to their perpetrators by not reporting.

Second, reporting means students encounter risks to their social networks. For example, students considered how labeling and reporting might hinder their ability to develop or preserve interpersonal relationships, which for some, include relationships with their perpetrator. Lastly, students worried they might lose access to college activities like sports, sororities, fraternities, and other student organizations, which would affect their long-term career goals. Several students discussed how reporting would add stress and take time away from their activities. Men who were intoxicated and Black men in particular expressed concern that they would be the ones accused of assault due to their alcohol intake or lack of racial privilege.

As we continue to address sexual violence in the Me Too era, this work encourages us to look beyond formal reporting policies and work to transform the social and cultural conditions that shape perceptions of risk among sexual assault victims.

Click here for more sociological research and expert insight on sexual violence!

Comments