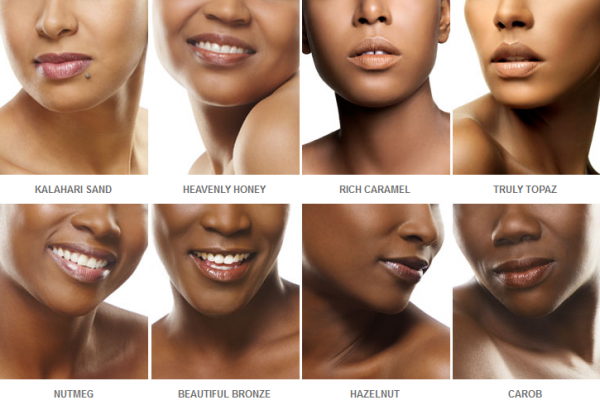

Skin color has long shaped the lives of blacks, as the advantages of being “light skinned” extend far beyond the socioeconomic. It even plays an important role in health outcomes. Health disparities between blacks and whites are well documented, and blacks often maintain higher rates of negative health outcomes such as mortality and morbidity than whites. The predictors of health disparities within the same racial group, however, remain largely unexamined. Thus, Ellis Monk investigates skin color as a form of discrimination in health outcomes between blacks.

So, how does one’s skin tone influence health disparities through discrimination? Monk uses various measures to investigate perceived discrimination and skin color through the National Survey of American Life (2001-2003) and face-to-face field interviews with respondents aged 18 and older. To assess perceived discrimination, Monk examines both perceived discrimination from whites and perceived discrimination from other blacks, in addition to the frequency of such discrimination. Monk measures skin color by first analyzing how the interviewer rates respondents’ skin tone, and second, how the respondents rate their own skin tone. Perceived discrimination and skin color are then examined in relation to four self-reported health outcomes: physical health, hypertension, mental health, and depression.

Monk concludes that the darker one’s reported skin color, the more discrimination they perceive from whites. Perceived discrimination among blacks, however, depends upon their placement in one of three categories: light skinned, medium-toned, and dark skinned. Blacks in the medium-toned category actually maintained more positive rates in mental health and were less likely to perceive discrimination from either white or black peers.

Still, the magnitude of the health disparities among blacks with various skin colors was found to be often equal to or greater than health disparities between blacks and whites. Monk also notes that blacks who reported higher levels of skin tone discrimination from other blacks also had higher rates of poor physical health. Monk argues that the study challenges common methodological practices that homogenize minority populations, demonstrating more nuanced life experiences affected by skin tone.