The thing about identity is that the stories we tell ourselves about our own are already forcibly consistent. We don’t need Facebook to make this so.

Last week there were several great posts on this subject. Nathan kicked things off with his claim that the social pressure to have a consistent identity is both subtly reinforced by how Facebook encourages – and constrains – the way we prosume identities, and that it potentially enables us to confront the fact that this consistency is an impossible and unreasonable standard to meet; identity is perhaps much more fluid than we’re comfortable thinking. Rob Horning was in agreement with at least part of this, suggesting that Facebook decontextualizes identity, making it seem less rooted in personal experience and more in data. Whitney went on to make a fascinating claim: that when our process of identity formation is recorded and made immediate in this way, it collapses the past into the present and removes temporal distance that basically alleviates the pain that’s all too often wrapped up in who we used to be.

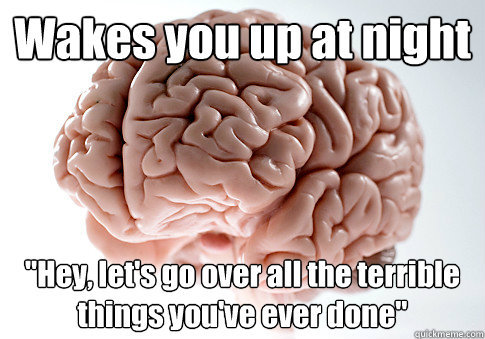

This is the point I want to latch onto. Because this is significant. This is really about our stories. And this is really about not only remembering a more immediate past, but inhabiting that past. We are faced with who we used to be and we become that person – “to read the words that came from that person is to be that person again”. We occupy our old self’s cognitive and emotional space.

This hurts. There are a couple of reasons why.