It was the first year of the new millennium, and at 16 years old, I bared my metal-clad teeth in a proud smile for what would be an appropriately hideous driver’s license photograph. On this momentous day in my young life, I volunteered to be an organ donor. My status as an organ donor is not something that I often talk about—mostly because it is not something I often think about. In fact, I often forget that I am an organ donor until someone makes a verbal note about it while looking at my (updated but still appropriately hideous) driver’s license picture, at which point I silently congratulate myself, and seamlessly forget until the next time. In theoretical terms, my organ donor status is not a salient part of my identity and it is rarely an attribute through which others interact with me. This is about to change.

A new feature on Facebook Timeline works to bring greater salience and greater visibility to organ donation. In a new “Health and Wellness” section, users can designate themselves as organ donors. This not only becomes a “Life Event” but is also shared with Friends via Facebook News Feed. With 72,961 active candidates currently waiting for organ donations, this feature represents peer pressure at its best. The powerful chiding of “everybody’s doing it” in this case, will save lives. But today, I want to talk about something else, something a bit more abstract. Specifically, I want to talk about the way in which this feature epitomizes the postmodern blurring of categorical lines that we so often reference here at Cyborgology.

Of particular note, are the blurring of lines between physical and digital; life and death; personal and public; and formal and informal.

Physical and Digital

Here, we have the most physical of physicality—the internal organs of the body—affected through digital action. To designate oneself as a donor is to promise a literal part of the physical body to another unknown person, whose body will be operated upon and potentially restored through the hands of a surgeon, the organs of a stranger, and the content of this stranger’s digital profile. Facebook users can literally share digitally their desire and intention to share physically.

Life and Death

Plainly, organ donation saves lives, but does so only through death. In its own right then, organ donation blurs the life/death dichotomy. The displaying of organ donor status through Facebook blurs this line further. Facebook is an avenue through which social and personal life are presented, enacted, interpreted, planned, and negotiated. Increasingly, it is also a space in which lost lives are remembered. With the organ donation feature, Facebook is now a tool through which users plan for their own deaths in a way that affects how they are seen during their lives. The display of organ donor status in one’s Timeline is simultaneously a tool of self-presentation, future memorialization, and practical direction about one’s end-of-life wishes.

Personal and Public

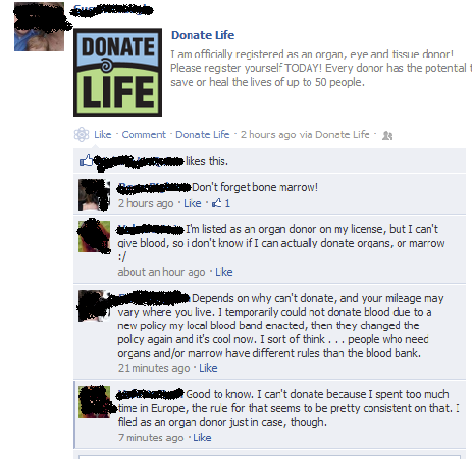

Discourses surrounding social media often discuss the changing relationship between public and private. In this case, I think we are looking at a changing relationship between public and personal. Privacy denotes that which is shared with no one, or only with a select few. Private information is that over which the subject can/should have control. Organ donation has never been “private” in this way, as it is openly displayed upon a public identification card. Rather, organ donation has been very personal, a choice about the body that each individual is respected to make for hirself. With the Timeline feature, this choice now becomes a public identity marker, something to be sociallydisplayed, commented upon, and potentially, conspicuously absent. Organ donation, as displayed through Facebook, is at once a deeply personal decision about death and the body, and a public display of generosity, fear, and/or general health—as those who cannot donate may find themselves publicly justifying their non-donor status.

Formal and Informal

The traditional designation of oneself as an organ donor is accomplished through wholly formal channels. This involves government agencies, official documentation, and sometimes lawyers. Facebook, a self-constructed and largely unregulated space is, by design, unofficial. And indeed anyone can designate hirself as an organ donor on Facebook, whether or not s/he is officially registered. Adding organ donation as a life event does not necessarily reflect one’s location on the donor list, nor does this action automatically add the person to this list. It does, however, link the user to the official registry, where Facebook Inc. encourages members to document their choice—making it “official.” Moreover, even if the user never registers, the public documentation of organ donor status might hold legal weight when, in the occasion of a person’s death, the family is asked to make difficult decisions regarding the body of the deceased.

Whether you think that Facebook has made a strong move in a positive direction, or has once again taken sharing too far, the organ donation feature on Facebook embodies the categorical melding that represents a connected era.