Editor’s Note: This post was written in response to PJ Rey‘s “Incidental Productivity: Value and Social Media” and the text is reposted from mrteacup.org.

PJ Rey has a very interesting post up at Cyborgology about issues of production and labor on social networking sites that has some connections with things that I have been thinking about.

The point seems to be a partial critique of the social factory thesis – that social networks exploit the social interactions of their users, turning it into a kind of labor. This critique turns on the idea of “incidental productivity.” Rey claims that some activity on a social network does not fall into the category of labor as defined by Marx; or to put it another way, the Marx-influenced theory of labor is not conceptually broad enough to cover every type of activity that occurs. Rey proposes the concept of incidental productivity, which seems to mean value that is silently produced as a side effect of some other activity that the user is engaged in. The important point is that users are not aware of the value that they are creating, so this is not labor.

So far, I agree with this. There is only one very small point of disagreement, which is where Rey says in the final paragraph, “A quintessentially Marxian question remains: Who should control the means of incidental production?” I claim that this concept of incidental production is ultimately the liberal-capitalist problem of consumer rights and protections.

This is obvious from Rey’s main example: Google tracks what users search for and what results they click on, and this data is used in various ways to improve the service. The data is a side-effect of our consumption of the service. This is productive activity, but not so different from filling out a customer feedback card after staying at a hotel. Of course, you have to opt-in to feedback cards and Google collects data automatically and invisibly. A better example might be a grocery store that secretly tracks the movement of customers around the store to see what sort of displays are most effective; or customer loyalty cards that track the effectiveness of marketing. But in all cases, the fundamental consumer relationship remains the same.

How would we think about our labor relationship to Google? We might talk about the early days of the web when individuals would create personal home pages containing list of useful links. This was eventually turned into a labor when companies like Yahoo hired people to do this same work to create a centralized directory of web links. Google replaced these web directories by returning to the distributed production of links and using an algorithm to interpret that activity as keyword tagging.

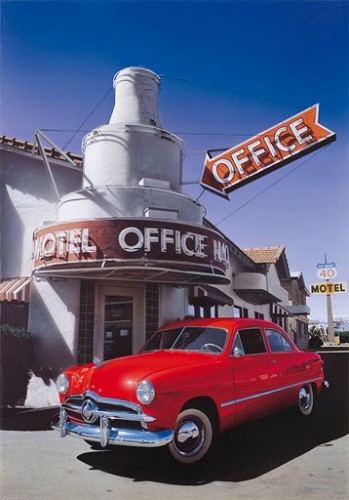

Returning to the hotel analogy, AirBnb has a similar relationship to the people who rent out their apartments. AirBnb is essentially a global distributed, decentralized hotel, where individual apartment owners are contracted to do all the work that occurs in a hotel, but just for their apartment. PJ Rey is drawing attention to the problem of customer feedback cards: who can use that data, who is it shared with, are customers informed and educated about privacy issues, and so on. But as I wrote in You Can’t Check Out of the Peer-to-Peer Motel, the social factory perspective is more concerned with questions analogous to “Is AirBnb generating profit by pushing risk on to its labor force?”

Obviously companies on the internet have an unprecedented access to customer data and this is only growing with the rise of social media, so the scale of the problem is well beyond customer feedback cards. But even so it is, for the most part, well within the ideological horizon of liberal democratic capitalism, and far from raising Marxist questions, actually risks further entrenching the belief that our fundamental economic rights derives from our social role as customers rather than workers. It’s no accident that the rise of consumer rights activism since the 1960s corresponds with the decline and defeat of the labor movement and the undermining of labor rights in the same period.

Mike Bulajewski (@MrTeacup) is a Master’s student in Human-Centered Design & Engineering at the University of Washington.

Comments 7

Cyborgology Weekly Roundup » Cyborgology — November 20, 2011

[...] and Mike Bulajewski responds [...]

PJ Patella-Rey — November 26, 2011

You put your finger on something important here. In challenging the conventional Marxian models of production (and the critiques of capitalism implied therein), there is a risk of falling into the trap of simply reifying neoliberal consumer rights rhetoric. However, I think it is a bit of an exaggeration to claim that that value created by social media users is solely an issue of consumption/consumerism. I maintain that questioning who controls the means of productions is in line with the best of the Marxist/leftist tradition and ought not to be conflated with the concept of consumer rights.

I do think that my discussion of “incidental productivity” was potentially misleading in that it failed to address the extent to which, on the Internet, every instance of production is, almost invariably, an act of consumption. The two can never really be separated the way they are in Marxist (or neoliberal) theory. This is why the language of “prosumption” is so important. We plan to host a discussion of the topic in the near future here on the Cyborgology Blog. Hopefully we can get deeper into these issue in light of that conversation.

locoyokel — January 5, 2012

I think there is a better word than laborer. It is producer. The user is a producer of media content. But, I think this view misconceputalizes the current paradigm which must be viewed in terms of the social network business model. The user is not an unwitting laborer, nor is he a unwitting producer. The user is a commodity, in a way that is crudely analogous to how one commodifies himself in prostitution. It follows from this that in the hypothetical situation in which a site like facebook agreed to let users get a share of its profits, the user would not be deserving of this because he produced content; s/he would share in the network's profits by agreeing to let the network expose him and his data to the advertisers that pay the network's bills. To continue with my crude analogy, facebook is the pimp. A useless middleman. There is really nothing new going on here. These social networking sites would never feel obligated to pay users for this because television commodified people the same way, and radio before that, by delivering an audience to advertisers, and no one ever paid anyone to watch TV.

locoyokel — January 5, 2012

Interesting stuff, in any case.

locoyokel — January 5, 2012

If the user was truly a producer, he would be charging the people viewing his page for a subscription to the content, which in the context of social networking, amounts to little more than the ability to stay connected. The fee would be an awkward request to make to friends and family who are just checking in to see what you're up to. Moreover, producer would be the one selling his friends and family to the advertisers. Would your friends really pay to see pictures of what you had for breakfast?

That exposes the real problem. It lies in the fact that the average joe is producing trivial content. The internet social networking is powerful technology. Unfortunately, it is being used predominantly to document banal details of everyday life that have no value to anyone except advertisers.

locoyokel — January 5, 2012

I need to apologize. I didn't read the piece fully and responded to the fact that you started about "social networking sites," without realizing that the topic you addressed is much broader than that (e.g. I would not really consider google a social networkimg site). So, sorry for making assumptions when I should have read you entirely before commenting. The points about customer satisfaction cards and internet users aggregating links for google makes the discussion broader and more interesting than I initially thought. Another example of similar "incidental production," is how the social activity on social networking sites like facebook helps to connect employers to laborers. The "social factory" has been described by others as the "social embeddedness" of the economy. Consider this:

"Much social life revolves around a non-economic focus. Therefore, when economic and non-economic activity are intermixed, non-economic activity affects the costs and the available techniques for economic activity. This mixing of activities is what I have called “social embeddedness” of the economy (Granovetter 1985) – the extent to which economic action is linked to or depends on action or institutions that are non-economic in content, goals or processes......One common example is that a culture of corruption may impose high economic costs and require many off-the-books transactions to carry on normal production of goods and services. Such negative aspects of social embeddedness receive the lion’s share of attention, especially when characterized pejoratively as “rent-seeking.” Less often noted, but probably more important, are savings achieved when actors pursue economic goals through non-economic institutions and practices to whose costs they made little or no contribution. For example, employers who recruit through social networks need not -- and probably could not -- pay to create the trust and obligations that motivate friends and relatives to help one another find employment. Such trust and obligations arise from the way a society’s institutions pattern kin and friendship ties, and any economic efficiency gains resulting from them are a byproduct, typically unintended, of actions and patterns enacted by individuals with non-economic motivations.

The notion that people often deploy resources from outside the economy to enjoy cost advantages in producing goods and services raises important questions, usually sidestepped in social theory, about how the economy interacts with other social institutions. Such deployment resembles arbitrage in using resources acquired cheaply in one setting for profit in another. As with classic arbitrage, it need not create economic profits for any particular actor, since if all are able to make the same use of non-economic resources, none has any cost advantage over any other. Yet, overall efficiency may then be improved by reducing everyone’s costs and freeing some resources for other uses."

http://www.leader-values.com/Content/detail.asp?ContentDetailID=990

Admittedly, this view is not sympathetic to the normative idea (i.e. the way things ought to be) that "incidental producers" should be compensated, but it is instructive in the sense of positive economics (i.e. the way things are).

To give the normative idea more traction it would behoove one to deconstruct the language and reframe the debate. The first thing would be to stop referring to "incidental production" as a social phenomenon. e.g. "social factory," "social embeddedness." If it is activity that ought to be compensated, then it must be called economic activity.

Thank you for you post.