During his plenary address a Theorizing the Web 2011, entitled “Why the Web Needs Post-Modern Theory,” George Ritzer was deeply critical of Siva Vaidhyanathan’s (2011), The Googlization of Everything (And Why We Should Worry), a book which has received a great deal of media attention in recent months, for it’s lack of theoretical foundations. The editors of the Cyborgology obtained the following excerpt from Ritzer’s paper:

During his plenary address a Theorizing the Web 2011, entitled “Why the Web Needs Post-Modern Theory,” George Ritzer was deeply critical of Siva Vaidhyanathan’s (2011), The Googlization of Everything (And Why We Should Worry), a book which has received a great deal of media attention in recent months, for it’s lack of theoretical foundations. The editors of the Cyborgology obtained the following excerpt from Ritzer’s paper:

The nature of, and problems with, a modernist approach are clear in Siva Vaidhyanathan’s (2011), The Googlization of Everything (And Why We Should Worry). We were drawn to this book because the title is similar to, if not an outright rip off of, two similarly modernist books written by one of the authors of this paper- The McDonaldization of Society (Ritzer, 1993/2011) and the Globalization of Nothing (Ritzer, 2003/2007). Thus we know from whence we speak in seeing Googlization as a modernist work and as such in understanding its liabilities (and strengths). In addition, while Ritzer’s works (mentioned above) use modern theories and ideas (e.g. rationalization) to deal with such clearly modern phenomena as the fast food restaurant and, more generally, the world of consumption, Vaidhyanathan employs modern ideas (not full-fledged theories) to deal with the arguably postmodern world of the Internet, Web 2.0 and especially Google.

Googlization can be seen as a modernist work in various ways. For example, Vaidhyanathan draws, although very superficially, on the ideas of a number of modern thinkers such as Veblen, Dewey and Habermas, but the work is virtually devoid of any discussion of postmodern thinkers and ideas. There is one exception, a brief mention of the work of Richard Rorty, but instead of drawing out its postmodern implications it is discussed in the context of the modernist concern for truth. This is related to the fact that Vaidhyanathan implicitly sees Google, as well as the Internet in which it exists, as modern phenomena and therefore as amenable to a modernist analysis. For example, the book offers a “centered” (as opposed a postmodern decentered) analysis with Google seen as exemplifying all of the positive (e.g. “liberty, creativity, and democracy”) and negative trends (e.g. “blind faith in technology and market fundamentalism”) associated with the Internet today (Vaidhyanathan, 2011: xiii). More importantly, Vaidhyanathan employs the most modernist of modernist approaches by employing throughout the book a grand narrative of the “googlization of everything”. By googlization, Vaidhyanathan (2011: 2) means that “Google has permeated our culture” and by everything he means, well, that everything, especially “us” (including the googlized subject and memory), “the world”, and “knowledge”. To this list, he adds toward the end of the book the googlization of higher education, students, scholarship, and research. Had the book gone on further, we would have been treated to endless examples of googlization.

In his conclusion, Vaidhyanathan (2011: 205) offers as a replacement for googlization his own grand narrative of the “Human Knowledge Project” which has a “single realizable goal in mind: To organize the world’s information and make it universally accessible”. In fact, in articulating this highly modernist goal, Vaidhyanathan is self-consciously using Google’s own mission statement to create a grand narrative that, he hopes, competes with Google’s while leading to a system that deals with many of the problems created by googlization.

We should also add that while some theorists and theoretical ideas are mentioned, The Googlization of Everything is a largely atheoretical work. Although it is published by the University of California Press, it is clearly a trade book aimed at a larger, non-academic audience. The result is that it is highly superficial and devoid of the insights that might have emerged from a more serious intellectual engagement with modern theory, to say nothing of postmodern theory.

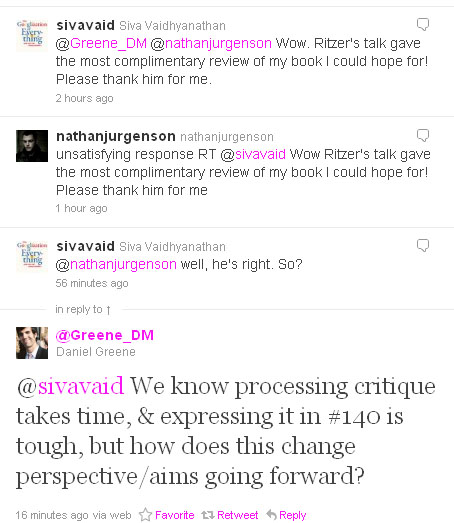

Of note, Vaidhyanathan recently visited the University of Maryland campus to give a talk that, like his book, was largely descriptive and lacking in theory. University of Maryland graduate student and past Cyborgology contributor Daniel Greene posed a critical question that Vaidhyanathan admittedly had no response for. “You are asking me to think?”, Vaidhyanathan (half?) joked. After the talk, Cyborgology editor Nathan Jurgenson invited Vaidhyanathan to engage Ritzer’s criticism via Twitter. Here is Vaidhyanathan’s response:

We have Ritzer’s criticism and, as yet, no real response from Vaidhyanathan (though, we will edit this post if there is one). Video of Ritzer’s full presentation streams below, with his criticism of Vaidhyanathan beginning around the 4:25 mark:

Comments 11

replqwtil — May 4, 2011

It's particularly interesting to see how Vaidhyanathan's answer to one grand narrative is to try and counter it with one he prefers. To me this is classic of modernist thought, and totally ignores any real concepts of post modernity. If there is a problem with the googlization of everything, which may well be the case even if this book doesn't make it, then I would see the critique coming from issues of process, in the digitalization of reality. This 'Human Knowledge Project' sounds like it would serve the same purpose as Google, so in what way does it extricate itself from the problems one might level at the Google? It seems almost silly to problematize a narrative only to counter it with a seemingly isomorphic narrative. Modernism strikes again!

b — May 4, 2011

I don't think "lacking theory" is a useful critique--perhaps that's why Siva had a hard time coming up with more of a response than "He's right." I think that it's your responsibility to ask a question that pertains to the stakes of the argument: what problem in the work will be addressed by bringing postmodernist theory to bear on it? That is, what do you find dissatisfying about the argument that "theory" will help to clarify?

PS--it's a little ironic to call Siva's title a "rip-off" if one is working in a postmodernist paradigm. Pastiche, perhaps. But rip-off? Doesn't that assume a centered discursive universe with clearly knowable and fixed origins that ought not proliferate? :)

Siva Vaidhyanathan — May 4, 2011

I'm not sure what you want from me. Professor Ritzer says I deploy a set of theorists I find useful and ignore a set that he finds useful. He is correct. I deploy those theorists to make my case and flesh out my arguments. And I ignore his. So I did not write the book he wanted me to write. Oh well. Maybe next time. But probably not.

I could go on at length about why claiming "Web 2.0" is not all that "postmodern." But why? I could argue Baudrillard is among the silliest writers on media and politics the world has ever seen. But why bother? We had all this out in the early 1990s. It's so over. Am I going to convince Professor Ritzer of that? Of course not. Should I bother?

I am not disappointed by Professor Ritzer's books. Well, that's probably because I had never heard of Professor Ritzer or his books before a series of tweets informed me of this talk. Perhaps I should just let him remain flattered by the "rip off" of the common American use of "-zation." When I get around to reading his books (which do sound interesting), I will certainly not give speeches based on the claim that he should have paid more attention to my theoretical framework or my ideas. That would be rude. I try not to be rude in my public comments about others' work. I try.

I have no substantial response to Professor Ritzer because he does not offer substantial criticisms of my work. He offers a vague and general criticism for which there is no response except to concede his points. He said he finds my book "disappointing." Well, I can't do anything about that. He finds my book "modernist." Well, yeah. Of course.

He also says my book is "superficial." Well, ok. Sorry. How should I respond to that? "No, really. There is a lot of substantial thought here. Let me make a list ..." All I can do is apologize for not working up to Professor Ritzer's standards of intellectual heft.

In contrast to Mr. Ritzer's superficial comments about my superficial book, Mr. Greene offered me a very insightful response to my talk. It was so good that I was stumped. I also did not hear it very well. But that's not that important. That comment deserved a serious response. And I was not prepared to think through it at that moment. Yeah, I was not in the mood to think. Sometimes that happens.

If Mr. Greene would like to address that comment again I will do my best to respond. He, certainly, deserves a serious response.

Dan Greene — May 5, 2011

Hi Siva,

Thanks for reaching out like this. We all gain a lot from having a civil discussion that moves beyond the one event or one book, to a network of new interests and actions. That's part of what I like about PJ and Nathan's blog, and loved about TTW2011--networked scholarship to approach networked topics.

I don't disagree with 'b' above. 'Lacking theory' isn't the most helpful critique in the world. And no one can read everyone. However, with the Ritzer critique, I think what Cyborgology was looking for was a taking account of one's assumptions, and how they affect your method and conclusions going forward. This is something we do in American Studies all the time, right? I'm a feminist empiricist, and that catches a lot of flack in an otherwise ethnography-oriented AMST department. That's OK. I gain a lot by thinking about how, at the outset of my work, an investment in certain kinds of demographic data might end up policing the borders of people's bodies. Or, by focusing on media form and political structure, like I did at TTW and will do at MLA, I know I miss out on deep content analysis but gain in institutional and infrastructural description. I think (correct me if I'm wrong guys) that's what PJ and Nathan were looking for from you by posting Ritzer's critique. Where are you coming from and where are you going?

So, now, with that out of the way, I'll restate my question from Tuesday. Basically I have a huge problem with the Skinner Box metaphor. My background is in clinical psych, and we don't use Skinner Boxes anymore because the stimulus+response framework can't take into account history, cognition, biology, sociality---a whole host of things. But even if you removed all mention of Skinner Boxes from your talk, I think it still felt like behaviorism, so that 'culture' becomes a set of behaviors rather than a sharing of meaning, a negotiation of power, or whatever. So Google's 'culture' is taking in all this info, they do everything to get it. Japan responds to this stimulus with their 'culture'--they sit outside their narrow streets in lawn chairs and get angry at robot cars that disrupt this. This elides any history of Japanese experience with invasion, any particularities of Maps interface design that might work better for some people rather than others, and any financial motivation for Google to map (I also disagreed with your point that Google's 'all your infoz r belong to us' seems innocuous or less commercial, the history of informatics, going back to Shannon and Wiener, is always about either capital or military or both). Among many other elisions. No aesthetics, no thoughts, no history, no struggle, no bodies. Just Google behavior and backlash behavior.

Basically, I feel like this stimulus-response framework ends up reifying the same party line that Google is advancing: information is disembodied and free-floating, therefore someone needs to keep it in order, that person is us and no one will really mind. Your answer just changes the 'us' from Google into 'everyone else'. What are the politics of information ownership? The aesthetics? The phenomenology? The emotion? The history? The culture?

PJ Patella-Rey — May 5, 2011

I think we would all agree that a work can be significant without engaging post-Modern theory. The discussion of post-Modern theory is only salient in the excerpt from Ritzer's paper because the topic of that paper was the applicability of post-Modern theory to the Web.

The underlying, and more damaging, critique that Ritzer makes here is to argue Vaidhyanathan’s use of theorists like Veblen, Dewey and Habermas is ad hoc, failing to engage the implications that the Google case study has for these theoretical frameworks and failing to acknowledge how the adoption of part or all of the theories might situate the analysis and color its conclusions.

The Googlization of Everything is polemical in nature. It is a critique of newly emergent institution and its associated ideology. All critiques, however, are based in a set of implicit or explicit values. Generally speaking, good theorizing systematically explores its assumed values, as these are the premises on which the conclusion is based.

Vaidhyanathan provides a series of descriptions regarding how Google has come to organize individuals, the world, knowledge, and memory. No doubt, these descriptions demonstrate increasing influence over our lives. Alone, however, they are insufficient to support Vaidhyanathan’s (p. 218) conclusion that “Clearly, we should not trust Google to be the custodian of our most precious cultural and scientific resources.” This question of trust implicitly appeals to our values and makes assumptions about the way the world operates. In both cases, it would be useful to appeal extant theoretical frameworks, and using these frameworks, to demonstrate how the conclusion logical follows from the observations.

Ritzer’s assertion that “The Googlization of Everything is a largely atheoretical work” should probably have been better substantiated. Nevertheless, just as Vaidhyanathan is probably right that we shouldn’t trust Google (even if his argumentation is insufficient to support this claim), Ritzer is correct in saying that this work is largely atheoretical. Broad appeals (p. 218) to “local republican values and global democratic culture” are simply too vague to provide a platform for a satisfying critique or to be the basis of an imagined alternative.

b — May 5, 2011

I should be clear that I have not read Mr. Vaidyanathan's book, and based on Dan Greene's very thoughtful and well-written question, I think that I too would have many critical things to say about it. But I am troubled by the way Cyborgology initially framed its critique of the work, and as far as I can see, the problem of that framing still stands (despite the very civil concessions that the charge of "lacking theory" may not be entirely helpful). I find it confusing, for example, that PJ Rey, for example, is taking Vaidyanathan to task for inadequate critical self-awareness about its own rhetorical conditions of possibility, when it seems to me that the charges levied against the book by the blog are based on a point of view that is itself naturalized, with its power moves and assumptions of value left unmarked. Can theory--especially if one means continental (not analytical) philosophy operating in a post-structuralist mode--fully expose and know its own conditions of possibility? Theory both elucidates and obfuscates in complex and radically non-identical ways across its different scenes of operation. If the moderators of Cyborgology agree, then they would do well to use "theory" or even "good theory" in a more circumspect manner when attempting to legitimate or de-legitimate an argument, scholarly or otherwise. "Theory" is all too easily fetishized, and its authority and efficacy

Again, this is not to say that I agree with Vaidyanathan's book. I'm speaking to a broader methodological dilemma that is being raised by the framing language used to counter the book's arguments. I also want to be clear that I am not arguing that the moderators of Cyborgology give up on their critique, but rather that they might find it helpful to pursue it differently. Insisting that a work explicitly situate itself in an intellectual tradition (and in something more satisfying than an "ad hoc" manner) is one thing. But to assume that "theory" writ large knows itself and can expose its own blindspots and operations of power (and policing of bodies, etc. etc.) when behaviorism (for example) cannot is to replicate the very problem that Cyborgology seems to want to solve.

b — May 5, 2011

--and I apologize for some of the editing errors in the previous post (but comments can't be edited by the commenter once they've been posted). The biggest one is at the end of the first paragraph: I meant to say that "'Theory' and its authority and efficacy are all too easily fetishized.'"

Just to have all my cards on the table, I should also note that that was a criticism once made of my own scholarly work by a wise advisor. :)

PJ Patella-Rey — May 5, 2011

b,

Thank you for raising an important issue.

First, let me note that I was only trying to extend and clarify for the readership what I felt were the most important aspects of the Ritzer's critique, which, incidentally, are also those aspects that remain to be adressed by the author.

I agree that there are major epistemological stakes in this debate (i.e., what constitutes legitimate theory). However, I rather disagree with the characterization that I am naturalizing certain assumptions about knowledge production. I'm very open to the idea that we ought to re-evaluate/expand what the academy accepts as legitimate knowledge. The critique I advanced was largely an immanent one.

Vaidhyanathan's project is a rather conventional academic book published by an academic press. There are set of accepted norms about what constitutes legitimate theory production in this context (including, as you note, positioning oneself with respect to relevant, ongoing conversations - both to demonstrate the contribution a work makes and to acknowledge what assumptions a reader must accept if s/he is going to embrace the conclusion). I simply observe that Vaidhyanathan's book does not adhere to these standard practices for theorizing in a university press publication.

Whether these standards should be changed is a different conversation entirely (though no less important! See my post on blogging today). Vaidhyanathan gives us no indication that he is trying subvert norms of academic publishing, which is why I feel rather comfortable applying them to his work.

For me, Ritzer's critique merits attention insofar as it's consistent with a much broader agenda of encouraging more creative and rigorous theorizing about the Web than we've seen in past decades.

The Rise of the Internet (Anti)-Intellectual? » Cyborgology — October 17, 2011

[...] center. None of them provide a rigorous historical or theoretical treatment of their topics. (We called out Siva Vaidhyanathan on this blog after attending his a-theoretical talk at a public [...]

The Rise of the Internet (Anti)-Intellectual? » OWNI.eu, News, Augmented — October 19, 2011

[...] center. None of them provide a rigorous historical or theoretical treatment of their topics. (We called out Siva Vaidhyanathan on this blog after attending his a-theoretical talk at a public [...]

The Rise of the Internet (Anti)-Intellectual? « n a t h a n j u r g e n s o n — October 19, 2011

[...] center. None of them provide a rigorous historical or theoretical treatment of their topics. (We called out Siva Vaidhyanathan on this blog after attending his a-theoretical talk at a public [...]