On July 6, 7, and 8 the police established a thick cordon around the Hamburg Messe and Congress where the G20 was taking place. It separated delegates from the thousands of protestors who had converged on the city.

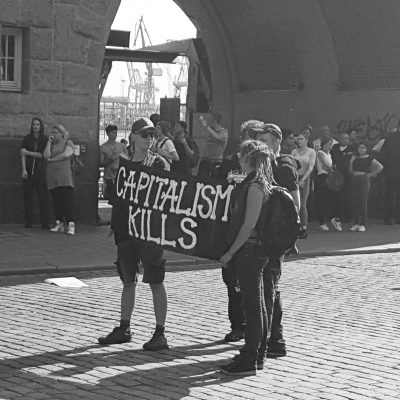

From the distinctive, red Handmaid cloaks worn by Polish feminists, to Greenpeace in boats off the harbour, to radical and Left groups in Europe, the G20 brought together diverse communities of protest from around the world. Protestors were there to tell leaders of the world’s most powerful economies that they were doing a terrible job of running the planet.

Not all of the protests were peaceful. The violence by some protestors and by the police against them has formed a substantial part of the reportage about the G20. In this post, I share some experiences and insights from the protests and their mediation.

The anti-Trump protests, the anti-Caste discrimination movements and activism on Indian university campuses against the Modi government, the ‘Science March’, the Women’s Marches, protests against Michel Temer in Brazil, #FeesMustFall and its sister protests in South Africa, and the post-Brexit marches to name a few, have captured local and national attention.

These protests have generated discussion about the shifting dynamics of political participation, popular resistance, and media, from the documentation of clever signs, the transition of protest memes from the online to the offline and back again, to the inspirational images of Saffiyah Khan and Ieshia Evans confronting violence.

The anti G20 protests in Hamburg have resulted in damage to property, and violence by the police against protestors. According to a legal team representing activists, 15 people have been arrested and 28 are in preventive custody. For a few hours I got to observe how the police were responding to protestors. I did not witness any specific acts of violence by protestors. It was also not always easy to tell a ‘protestor’ from anyone else who might have just been an aggressive element on the streets. The city felt chaotic that day.

Late in the afternoon, many of us were in a park on Helgoländer Allee. We could see water canons, unmarked black vans, police cars lined up ahead, and protestors on the bridge above us. Formations of police in riot gear, their faces invisible behind visored helmets, jogged past. Protestors on the ridge above us were yelling. Riot police were running at us through the park, and chasing protestors down from the ridge. Suddenly, we were running but not sure exactly of where because police were coming at us from two directions. Many of us in the park – curious locals, tourists, media workers – we were not part of protest groups, and yet felt intimidated by these swarms of police. “If you’re wearing black, they’re not asking questions, they’re assuming you’re a protestor” said someone behind me. ‘Schwarzen block’, or Black Bloc tactics were in evidence.

An hour later, we walked down Helgoländer Allee towards Landungsbrücken station. Someone in our group wanted to try Hamburg’s famous Fischbrötchen – cured fish, remoulade, and pickles in bread – so we thought the touristy harbour promenade area might be a relatively quiet place to catch a break. It turned out that it wasn’t off limits. The police were going anywhere there were protestors, some of whom also wanted Fischbrötchen. The police sprayed protestors with water canons, and started pushing and shoving protestors and non-protestors alike.

Again, we saw ourselves surrounded by riot police yelling raus, raus (leave, go). We didn’t feel particularly heroic and wanted to leave, which we eventually did, but only after being pushed down the promenade. We broke away as soon as we could. Protestors and police continued down towards the St.Pauli Fish Market. Above us customers at the Hard Rock Cafe were filming everything, Pilsners in hand, and chicken wings for after.

FC⚡MC

Before getting to witness police tactics of intimidation, my day in Hamburg started by exiting the Landungsbrücken subway station and walking up to Millerntor stadium, home of the local football team St. Pauli (also associated with a brand popular with Punk and ‘alternative’ consumers), where FC⚡MC had their headquarters.

FC⚡MC describes itself as a “material-semiotic device for bloggers and Twitterers, editorial collectives and staff, video activists, free radios, precarious media workers and established journalists to re-invent critical journalism in times of affective populism.” With technical support by the Chaos Computer Club, and something of an heir in the IndyMedia tradition,FC⚡MC is a space for and to support media workers reporting on the G20.

Anyone with accreditation could a space to write, edit, and post reports online. It was not difficult to join FC⚡MC. All you had to do was accredit yourself via their website. The accreditation letter and wrist tag were something of a relief later in the day when we encountered the police.

While the MC in FC⚡MC is clearly ‘media centre’, the ‘FC’ expands into charming, ephemeral “suggestions from the outside” everytime you refresh the webpage: “FC might mean Free Critical, For Context, Free Communication, Future Commons, Fruitful Collaborations, Friends of Criticism, Finalize Capitalism, Flowing Capacities, Freedom Care, Flowing Communism, or even Fight Creationism. But remember: these are just suggestions from the outside. The FC⚡MC itself, in its autonomy and autology, might choose different ones.”

FC⚡MC planned to organise press conferences following developments of the G20 and based on the reportage and views of alternative and independent media and activists. As protests grew however and got to dominate the coverage of the event, I couldn’t help feeling that it possibly put FC⚡MC in a difficult situation. FC⚡MC was also a space for media workers aligned with protest groups, particularly Left-leaning groups. But, FC⚡MC could not directly promote protest actions. Reporters talking about police violence and the conditions around the protests were, however, given a platform by FC⚡MC.

Drawing on support and resources from its networks, rather than owning the infrastructures of media production themselves, FC⚡MC attempts to introduce diversity in the media ecosystem by itself being a pop-up. It is unclear if they will emerge elsewhere, and that is perhaps the point. This begs the difficult question of what kinds of control – editorial or otherwise – are lost and gained in adopting this flexible, in-a-box approach.

The ‘Inappropriate’ Selfie

https://twitter.com/JimmyRushmore/status/883460508078178304

The inappropriate selfie is fresh social media meat. A recent selfie from the Hamburg protests, with a sarcastic caption by @JimmyRushmore and re-tweeted more than 35,000 times in two days, foregrounds the struggle around selfies and mediated political participation.

(There is a lot going on in this particular image, and in the online discussion about it. My intention in this diary is not to attempt a full or in-depth analysis, but to share some impressions that might inspire future discussions.)

The tweet was about selfie culture, tech object fetishisation, and the irony of a selfie with the latest iPhone (one tweeter was quick to point out it was not an iPhone 7 but a 6) in a protest against Capitalism.

Rushmore’s tweet may have been one of those throwaway comments that makes for great Twitter: a critique of pop culture, ruefulness at the mediation of everyday life through social media, and the struggle to live a consumption-conscious life in the absence of infrastructures to support this consciousness. But it has become a lot more than that now.

Like funeral selfies, or Holocaust Memorial-selfies, the discussion around this selfie is about the question of legitimacy: Are your politics legitimate if you’re taking a photograph of yourself in a riot against Capitalism? What are you, some kind of riot hipster? (“Riot hipster” is a Reddit word).

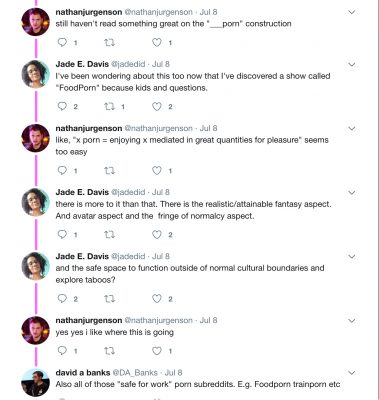

In a 2014 AoIR conference paper, Martin Gibbs and his collaborators discuss controversy around funeral selfies as an example of ‘boundary work’, that is rhetorical work negotiating the space between the legitimacy and illegitimacy of online behaviour. Similarly, “riot porn” is a word that has come up in some offline conversations to discuss the media’s emphasis on the riots and protests, as well as how the G20 protests were a spectacle that many of us participated in.

A recent conversation on Twitter (that includes Cyborgology folks) takes on porn as a suffix: there is a question of legitimacy here, again, and about the policing of how something is to be enjoyed.

Paul Frosh discusses selfies in terms of how they tip the balance of ‘indexicality’ that all photographic images are about: “It deploys both the index as trace and as deixis to foreground the relationship between the image and its producer because its producer and referent are identical. It says not only “see this, here, now,” but also “see me showing you me.” So in this case, you have: ‘see me showing you me’ participating in this particular political event that is dangerous; see what I risk for my politics. This selfie is unadulterated hyper-masculinity caught up in establishing its own calibrations of legitimacy.

Almost as soon as Rushmore’s tweet went up, so did digital sleuthing: Is this a real image or a doctored one? In a long Twitter thread following the selfie, Rushmore finds himself fending off these discussions, but image literacy is now an inescapable part of the mediation of images of events.

Back

Hamburg was shut down on Friday, and many of us had to walk some miles around the heavily secured Messe area to get to the only train station working that day. Close to twenty cars were burned and property was damaged. Hamburg is not without its rich history of countercultural and protest politics. These sorts of events are not new here but are infrequent now (unless perhaps you’re a newly arrived brown immigrant). A German friend who has been involved in activism for many years watches videos from Hamburg and says “good, it is good, let the protests come back to Hamburg. We need to deal with what has happened.”

Maya Ganesh is a tech researcher, writer, and feminist infoactivist living in Berlin

.