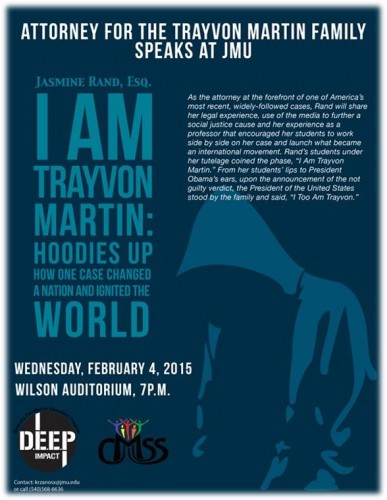

Jasmine Rand, lawyer for Trayvon Martin’s family, came and spoke at my university last week. I held my breath as she walked out on stage. She began with the emotional announcement that we were on the eve of what would have been Trayvon’s 20th birthday. Along with a crowd full of students, professors, staff, and members of the community, I settled on the edge of my seat and listened eagerly for what this woman, in this moment of racial upheaval, had to say. As I tweeted just before the talk: this was a big deal.

The talk had no official hashtag, and the #JMU hashtag was entirely populated by tweets about the basketball game going on at the same time. With no backchannel and no one to tweet with, I put my iPad away. Fine, I thought, Turkle-esq undistracted presence it is.

About an hour later, I was somewhere between bewilderment and seething anger. The talk was not just disappointing, but downright offensive. This person, this supposed defender of justice and crusader for equality, had used the death of a young black man and the subsequent non-conviction of his killer as a platform for self-aggrandizement (and I imagine financial gain). With a captive audience of young minds—college students in a prime position to take action—she, a white woman, spent 45 minutes talking about her personal journey through law school, and about 15 minutes talking about race relations. In those 15 minutes, she politely preached colorblindness. Not only did she fail to address systems of racial oppression, but advocated “love” as the penultimate solution.

I believe in love as much as the next person and I agree that love should be part of both academic and political discourse. But what about Stand your Ground? What about Stop and Frisk? What about broken windows policing? It’s not lack of love that makes black men disproportionately vulnerable to police violence. It’s wasn’t lack of love that failed to indict the officers who killed Michael Brown and Eric Garner. Love would not have saved 12 year old Tamir Rice.

The talk ended and the organizers prepared the room for questions. Remembering my dormant iPad, I pulled it out. That was SO bad, I thought, someone must have commented. No dice. The #JMU Twitter feed was still mostly basketball, speckled with excited announcements of Rand’s upcoming talk. Including mine. Ugh.

If the talk was bad, the question answer session was even more troublesome. Young women stood up, profusely thanked Rand, and asked for advice on getting into/through law school. Faculty cordially asked her to expand on her love thesis. People clapped after each of her responses, which consisted almost entirely of “follow your heart” and “be true to yourself,”along with a personal story about how she does just that. One brave student tried to challenge her, but the question wasn’t perfectly articulated. She took the opportunity to twist what he said and then refused to answer. The crowd clapped for that, too.

I was screaming inside my head. Will nobody stand up and force the issue of systemic racism? Will nobody ask her to account for the conditions under which Trayvon Martin’s killer was deemed innocent by a jury of his peers? Will no one push this woman, acting as a voice for a social justice movement, to get outside of herself and address the devastating failures of the justice system? What is wrong with everybody!?, I wondered. Do they have no courage, or do they simply not get it?

Amidst this internal rant, I realized that I am them. I was not asking these important questions. I was the one with no courage. About this time, one of the colleagues I was sitting with signaled that she was ready to leave. In a daze, I got up and walked with my small group out into the lobby and then into the cold night air. We were all silent for a moment. And then, to my great relief, we all exploded into conversation about our dissatisfaction with the talk. And yet, none of us spoke up in front of the crowd. The content of the talk, including questions and answers, was wholly uncritical. Our dissatisfaction, and undoubtedly, the dissatisfaction of many in the room, was never brought to the record.

This bothered me a lot. It still does. It is especially bothersome because she is a voice of authority, and many students in the audience were therefore primed to receive whatever message the talk produced. Critical questions by other figures of authority—such as faculty like me—could have changed that message. We didn’t do it. I didn’t do it.

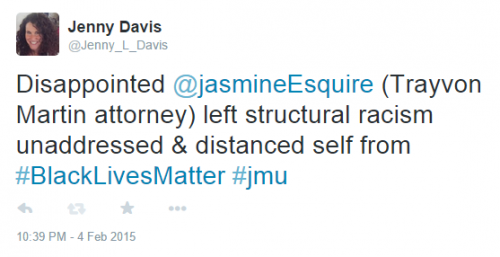

I went home and ruminated. In an effort at damage control and an attempt to put something on record, I tweeted this:

The tweet was entirely ignored. No favorites. No retweets. No replies. It just hung there with nothing to latch onto and no one to address[i]. There was simply no platform in which to embed the message. There was no conversation for this tweet to disrupt.

It is here that we see the power of a hashtag. A hashtag does not just organize discussion, it also creates a space for discussion and sets the expectation that discussion will take place. I put my iPad away at the beginning of the talk because there was nowhere for me to place my thoughts; nowhere for me to go to read the thoughts of others. I didn’t livetweet because it made little sense to do so.

The consequences of this were substantial. The communicative effect of a hashtag is not additive, but productive. It doesn’t just tack onto existing discourse, but changes the discourse itself. The message of Rand’s talk included her words and those of the audience in the room. It could have also included the content of a Twitter feed. The content of this feed would not only affect the meaning of the talk as a whole, but primed those listening to hear Rand’s words from a different, more critical, perspective. Perhaps this would have encouraged others to express their own critiques through social media. Perhaps it would have incited defensive responses by Rand’s supporters. Perhaps more of us would have been willing to break through decorum and press Rand to defend her position. It could have been a fight. Instead, it was a willowy hour of personal stories and sanitized contentions.

In circumstances of differential power and authority, the hashtag is an important means by which the masses can become part of discourse. In all of its simplicity and seeming banality, the hashtag holds liberatory functions. It provides a space for comment and a platform for dissent. It augments discourse not just through the use of multiple media, but through the inclusion multiple voices. The absence of a hashtag—intentional or not—therefore becomes a mechanism of silence. Without a clear platform, we can speak, but to whom and to what end?

Follow Jenny Davis on Twitter @Jenny_L_Davis

[i] I included the speaker through an @connect, but her page has strict privacy settings and my message was not displayed. Her privacy settings are in place for good reason. I Imagine Trayvon Martin’s lawyer would otherwise be bombarded by ridicule and threats by white supremacists.

Comments 3

Comradde PhysioProffe — February 9, 2015

It makes a lot of sense that having a convenient hash tag would have encouraged critical questions and commentary. But I wonder why you felt inhibited to ask a question orally in the room, as others apparently did?

Jenny Davis — February 9, 2015

I think that's a really important question. It's one I've struggled with.

Part of it for me was the venue was so institutional, it felt somehow rude or wrong to come out on the attack. Maybe others who were there could articulate it better. We wouldn't have been in trouble, per say, but this was supposed to be an honored guest, brought in by student groups. I think most of us were primed for it to be a community building event that we would all support. I certainly didn't come prepared to be a critic.

Tammy Castle — February 9, 2015

I also felt inhibited, for a couple of reasons. Like Jenny said, it was an honored guest brought in specifically by multicultural student services. We were shocked at the presentation, believing it was going to be more focused on collective action and social movements as advertised on the flyer. In Justice Studies, we encouraged our students to attend for this reason. We were caught a little off guard by the almost exclusive focus on her narrative and career exploits, but we listened to the end hoping that at least some of this would be addressed.

It also became clear that critical questions had no place during the Q&A and her response to one student question in particular, in which she shut the student down rather rudely but was applauded for it. Although I wanted to challenge her, especially after the colorblind nonsense, I believed the points would have been lost. The only thing we could do was engage with our students about their experiences.

If I had commented at the Q&A, I'm not sure in that moment I would have been able to hide my disgust at the whole spectacle. Exploiting the family and deaths for personal profit...