The murder of Mike Brown by Ferguson police officer Darren Wilson has catalyzed an already fast-growing national conversation about outfitting police officers with cameras like the one shown above. These cameras, the logic goes, will keep officers on their best behavior because any abuses of power would be recorded and stored for later review. Officer’s behavior, much like an increasing amount of civilian behavior, will be subject to digital analysis and review by careful administrators and impartial juries. This kind of transparency is extremely enticing but we should always be critical of things that purport to show us unvarnished truths. As any any film director will tell you: the same set of events recorded on camera can look very different when viewed from different angles and in different contexts.

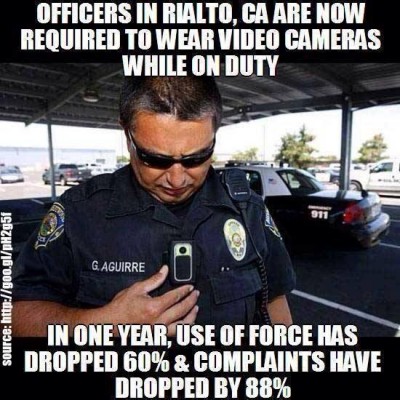

As of this writing the whitehouse.gov petition to pass a “Mike Brown Law” that would require police departments to put cameras on all of their officers has amassed about 150,000 signatures. Should the federal government decide to act on this proposed law, it would make thousands of law enforcement agencies join the handful already testing these systems. Denver Colorado and Rialto, California already have pilot programs in place and the quotes from officers point toward a single conclusion: Cop-mounted cameras are meant to compete with, and ultimately discredit, citizens’ filming of cops.

One need only read the source article for that image to get a sense of why police departments are even considering filming themselves: Video is compelling evidence and its always good to have your own video that provides your own interpretation of events. One officer praises the cameras for capturing what a nearby cell phone video did not: “Now you can see the [suspect] punching the officer twice in the face before he hits him with his baton.” These sorts of quotes are almost always paired with an assurance that these systems do not get officers in trouble. From the same article: “I heard guys complaining it would get them into trouble, but I’ve had no problems so I’m OK with it[.]”

Surely some cameras will capture more video than others and a camera that is automatically triggered by the unholstering of a weapon can probably start recording faster than a nearby civilian fumbling for a phone in a pocket or purse. Having an extra few seconds of footage can catch that quick punch to the face, but really it is the opportunity to offer a believable description or interpretation of video that is really powerful.

Ben Brucato, a friend and department colleague studies cop watch groups is quick to point out that, “the very proliferation of media documenting extreme police violence, resulting in severe injuries and even death to civilians, speaks to the limitations of visibility as a protective power.” Brucato’s work has shown that while video of gruesome police violence surfaces every month, police use-of-force incidents have remained stable or slightly increased in spite of decreasing violent crime and increased officer safety. His interviews with organizations that train people to film police have shown that while video is important, it became clear that what was really needed was training in how to “write and add voice-overs, to provide the subjective accounting for video contents that can never be self-evident.”

Recall that during the Cecily McMillian case, the police were able to turn grainy, almost useless video into incontrovertible evidence of assault on an officer. It is this power to say what a video depicts that is the true source of power. The ability to say what one is seeing, to declare what is the “official depiction of events”, cannot be wrestled from the hands of authority with cameras alone. Mainstream media, when looking for video of an incident, will undoubtedly play the official police footage and then (maybe) show more video from a citizen’s perspective.

If Ben’s work teaches us anything it is that cameras are not synonymous with oversight or power. Ever since the video of the LAPD beating up Rodney King surfaced in 1991, police departments have recognized that videotape can be a formidable opponent to falsified reports or fellow officer’s court testimony. Video can draw a lot of attention to incidents that previously happened in the shadows, obscured by dark alleys and abuses of power. Now that more people than ever have a high definition camera in their pocket and the means to share it with millions, police departments must confront video with video.

Huge thanks to Ben Brucato for help with the post. Quotes come from his recent presentation at the Questioning Power conference.

Comments 3

Cameras on cops isn’t the same as cops on... — August 29, 2014

[…] […]

Cyborgology Turns Four » Cyborgology — October 27, 2014

[…] work on gender, capitalism, and ‘Lean In’ culture, and David Banks’ continued discussions of power and surveillance. Taking on a new editorial role this year, I hope to foster this kind of engagement among both […]

Obama’s police reforms will strengthen the police | Nathan L. Fuller — December 2, 2014

[…] advantage. In a post countering several arguments in favor of body cameras for police, David Banks shows how police officers already using them reveal their intent: “Cop-mounted cameras are meant to […]