This is the second in a series of autobiographical accounts by Cyborgology writers of our early personal interactions with technology. Half autoethnography, half unrepentant nostalgia trip, this series looks at what technologies had an impression on us, which ones were remarkably unremarkable, and what this might say about our present outlook on digitality. Part 1 can be found here.

In order to understand my relationship with computers, you need to understand that I have terrible handwriting.

Do not try to tell me that yours is worse. It isn’t. I promise. My bad handwriting is a combination of a number of different things both contemporary and historical, including an inability to hold a writing implement in a way that even approaches comfortable, impatience, the fact that I literally never learned to form letters “correctly”, and probably some neurological stuff that goes formally undiagnosed. I don’t just write illegibly, I write illiterately: I skip letters, I place them out of order in words, I can’t space or block sentences. I completely abandon rhyme or reason when it comes to capitalization (my punctuation is impeccable, though). I’m not dyslexic, not that we’ve ever been able to determine, though again, there probably is something going on there. I just… can’t write by hand. At all.

And I’m a writer.

More, I’m a writer because of computers. I can’t emphasize this enough: Without digital technology, I would not be a writer, at least not the way I am now. I’ve written before that computers gave me my words. That’s true. That’s the backbone of this, the place from which we have to start. Everything else proceeds from there.

~

The first computer – the first digital anything – that I remember was my father’s little Kaypro. I loved that thing. I loved everything about it. I don’t remember when or how it entered the house, or if it was just always there, but I remember how big it seemed, how bright the green characters on the black display were, the sound of the keyboard, the louder and vaguely alarming rattly sound of the printer. I gave them names: They were Puter and Ticky.

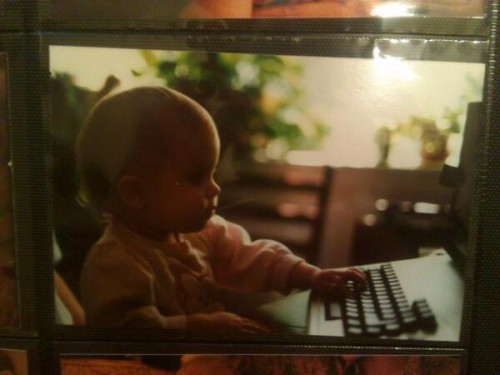

I also used them. It started very early. Look:

God, I don’t even know how old I am there. It’s my parents’ old apartment, so I can’t be more than one.

The thing is, for a long time the idea that I could use the keyboard to assemble the various letters into coherent sentences was alien to me; I knew it was possible, I just had no idea how to go about doing it and didn’t yet feel a need to learn. What I did do was repeatedly mash my hands on the keyboard and then force my father to print out the resulting gibberish and read it aloud to me. I laughed. Oh, how I laughed and laughed. It was a simpler time.

Then, much later, we got the Apple IIci.

Now this was quite exciting. There was color! There was a GUI! AND. There were games. I’d played games before at school – there was Odell Lake and a few other things I can’t remember, though I don’t think I came to Oregon Trail until a while later – but these games were complicated and colorful and weird and had involved stories and were so, so exciting. I should note at this point that I never had a game console or indeed a TV – growing up, though I did hang out with friends who did. But I never played. Until the computer.

~

This is the other thing you have to understand. For me, digital technology is about friends, about work, about connection, about entertainment, about research, about sex, about identity, about fandom, about politics, about all the stuff that it’s about for most people in various different combinations. But for me what it’s really about, besides words, is play. Play came before the words. In fact, if I’m being honest, play is part of what made the words themselves possible.

These weren’t just pixels. These were worlds. I’d spent years creating other universes in my head; now here they were in front of me, and so what if they were small and grainy and at best rendered in 256 colors? For a lot of kids my age it was no big deal. For me it was a revelation, and I had no idea – sitting there and playing the demo of a knockoff Star Trek game with a keyboard and trackball – the degree to which it would shape my life for decades after.

~

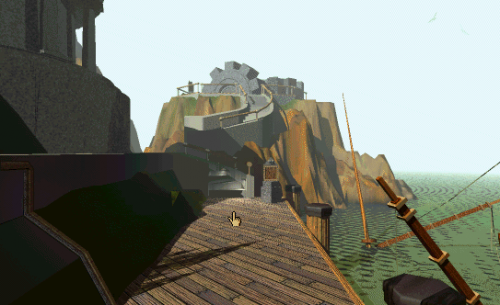

What really changed everything, I think, was Myst.

A lot of people don’t remember Myst anymore. Which is strange, because when it was released it was hailed as a new chapter in computer games, something that would forever alter what we thought was possible in the genre(s) and what could be done with the medium. Myst’s genre – point-and-click adventure – hasn’t died, but it’s definitely become a niche genre rather than the juggernaut that people were predicting. Nevertheless, for me it really was that kind of watershed moment.

Myst looks incredibly dated now – its pre-rendered background screens are static for the most part and clumsy to the eye. What movement there is consists of grainy in-screen Quicktime films. Yet it was amazing to me, a game that was fundamentally about an atmosphere and a sense of place, a space in which the entire point was to explore. It was also a safe space, where death was impossible, that nevertheless contained a definite sense of unease. It was made to feel open but was actually quite linear, plotted out beforehand, though there were several possible endings. One of them, the “best” one, led to the player being given Myst island and the freedom to return to it whenever they wanted. After I finished the game, I found myself booting it up many times after, simply to wander around and be in that place.

I think it was that open space that made me realize that I could create within it. I could fill this digital space with my own stories. A lot of people have regarded video/computer games as things that have made an entire generation imaginatively lazy; for me it was an explosion of imagination. These were tools that I could make use of, an imaginative space that I could use as raw material for the creation of my own fictions. Much later came consoles, came Half Life and Portal and Enslaved and Journey and The Last of Us and Bioshock and Spec Ops: The Line and The Walking Dead (point-and-click, appropriately), but I owe my entry into that world to a little pre-rendered window on my dad’s Apple IIci and a few crappy minutes of live-action footage.

~

But the last piece slotting into place was the internet.

I think I first recall using the internet with – as usual – the assistance of my father, who had gotten a home connection for work – like so many of us, the sound of a dial-up connection stirs deep memories in me. I didn’t immediately discover actual real-time interaction with other human beings until a good bit later, though I was vaguely aware of chatrooms. What I discovered was fandom – mostly fan sites for movies and TV that I loved (by then I had regular access to television), most particularly Star Wars and later on The X Files.

Star Wars was my first experience of fanfiction – in middle school – and I distinctly remember being confused about whether or not these works of fiction were actually canon in some way. What I first came upon was – of course – fairly sexually explicit, and I remember being both intrigued and vaguely troubled by that. But I was hooked. I soon gained an understanding of what exactly I was seeing and devoured whatever I could find. It was yet another moment of revelation. People could write fiction about the stuff they loved and share it with others. Not authors but just people.

People like me. And at last, a method of writing that for years had been awkward and painful was no longer an obstacle.

Right around this time I met someone who would remain my closest friend all through high school, though we later had a falling-out from which we haven’t recovered. She had AOL, and it was there that I discovered AIM, other fans, other friends who I had never met and might never meet, but as a weird, lonely kid in school, the sudden ability to make contact with a world of other people like me was intensely liberating.

At this person’s house were also yet more games – Zork Nemesis, Zork: Grand Inquisitor, and some of my first exposure to shooters in the forms of Rainbow Six, Quake and Soldier of Fortune. This was something else: games could be violent, and that wasn’t frightening to me but rather massively exciting (I had seen games like Mortal Kombat and Doom, but had only had limited contact with them). I now realize that, among other things, I was very angry during that time; here was an outlet for that anger.

High school was marked by an even deeper immersion into fandom and the friends I found there, partly as a result of the emotional difficulties I had in a transition from a small private middle school to a public high school that contained, as I recall, about a thousand students to a class. Life was not fun. Fantasy was an escape, and while I had made some clumsy attempts at fanfiction before, now I took to it with a kind of desperation. I could write things, and other people would like them. There was instant ego-propping-up-of. I think my parents were troubled by this – we now had a fancy new iMac and I was spending a huge amount of time on it – but at the time I insisted that I needed what I was getting from it and I maintain that that was largely true. It wasn’t indulgence; it was a survival mechanism. Digital technology, at that point, was a lifeline.

It was also play with identity in a sense that I had never done before. I discovered fandom roleplay, a perfect analog to the pretending I had done as a child. I could write and perform in digital space as other people. I could lose myself in that, try on different things, see how well they fit with my understanding of who my adolescent self was becoming.

I met my now-husband through the internet, via a comment on a message board about looking for other local fans of a band I was into. He contacted me. We became friends, and then more than friends.

Then the internet went away for a while.

After high school I “took a year off”, which turned into two years, which turned into relative poverty and a string of awful retail and temp jobs. During that time, I had an old PowerMac in my one-room apartment, but I had no connection to what I had come to understand as the larger outside world, and it was deeply isolating. After a year or so of this, I managed to get a cheap dial-up line, and that was better. Two years or so after moving out of my parents’ house I finally started college, which gave me access to on-campus computers and a faster internet connection – now I had LiveJournal and AIM and fandom again, and it was a profound relief, a sense of recovering a deep part of myself that I had lost for a while.

Right around this time, I also (finally) got a cell phone, a dinky little flip phone that I probably still have in a drawer somewhere. I could dial a number and that was it. But it was still a remarkable feeling, being able to call someone at any time, anywhere I wanted.

(You might notice that I haven’t said much about cell phones in this piece and I don’t intend to; they’ve never played that big a role for me in terms of forming who I am or shaping my day-to-day existence. I’ve never owned a smartphone and I still don’t. My experiences with digital technology have been almost entirely focused around desktop computers, laptops, and now tablets.)

This is the thing about me and digital technology, which I think holds true for so many of us: What too many people still talk about – and what I think my parents saw then – as disconnection was, for me, connection of the most profound kind. Yes, it was all a sort of escapism, but it was also a tether to the things that made life emotionally bearable. That’s no longer as true – I don’t need everything I find here to stay sane – but it’s still where I’m creative, where I make friends, where I play. It’s so much a part of who I am as a person, of how I understand myself, that I can’t imagine myself apart from it. I wouldn’t want to.

This makes me realize something else about the people who talk about digital technology in terms of disconnection and who puff themselves up about eschewing it: Access to it is a privilege, but being able to choose to push it aside is a kind of privilege too. It denies the experiences of those of us who really benefit from it, for whom it represents liberation. Those of us who are socially awkward, queer in deeply queer-unfriendly spaces, disabled, isolated, questioning everything we are, questioning everything period.

It can’t mean the same thing to every person. This is what it’s meant for me.

Sarah is on Twitter – @dynamicsymmetry

Comments 3

Atomic Geography — January 2, 2014

After encephalitis caused brain injury I learned how much the built world is designed for the default human. No one fits in all ways, but most fit well enough for most purposes. But when you don't fit, the sense of exclusion and anger can be great. So I am glad that there is something that helps you just be in your skin.

For what it's worth it sounds to me like your neuro situation is dysgraphia (I'm not a doctor altho I play one on the internet).

http://www.ldinfo.com/dysgraphia.htm#top

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dysgraphia

Since my difficulty in this area is acquired, I have agraphia, although in a milder form than yours.

Thanks for this.

Friday Roundup: Jan. 3, 2014 » The Editors' Desk — January 3, 2014

[…] Cyborgology. Sarah Wananchak adds her own to the growing list of Techno-Biographies. […]

Robbie Svob — February 3, 2014

BioShock is a great game however you look at it. It's a bit like marmite you either love it or you hate it and we are loving it!