My Facebook feed, which had nearly gone dormant for the past week, is once again teaming with life; this means that somewhere, in a nondescript plot of desert, 50,000+ souls are packing tents, scrubbing dust from their hair, and beginning an exhausted journey home from their annual pilgrimage to the Burning Man festival. After last year’s impulsive decision to fund the the trip on student loan debt, I find myself once again relegated to the social media sidelines by financial constraints. One benefit of watching this year’s event unfold at a distance is that it has given me time and space to reflect on my experiences with Burning Man 2012.

I believe that festivals, in general, and Burning Man, in particular, do much to enrich the lives of their attendees. I frequently encounter people who consciously divide their life into time spent “on the Playa” (a term Burners use to describe the festival grounds) and time spent “in the default world” (i.e., the rest of their lives off-Playa). These phrases indicate just how much attendees experience Burning Man as a transformative event. Similarly, in my own personal experience, I found Burning Man to be an creative, inspirational, and highly collaborative environment, where people take time to treat each other as people and not as a means to an ends in some sort of transactional relationship.

With its 10 Principles, its rituals (e.g., Burning the Man, spanking festival “virgins,” respecting the solemnity of The Temple, lamp lighting ceremonies, etc.), and its symbols (Burners will instantly recognize this little ASCII icon: )'( ), Burning Man transcends the mundanity of default life and takes on aspects of (what Durkheim called) “the sacred.” In fact, I think it is perfectly legitimate to describe Burning Man as the foundation of a secular religion.

While there is much to discuss regarding the significant place that Burning Man occupies in the lives of its participants, I’d like to focus on the complex social and economic relationship Burning Man has with the default world and how this relationship reflects the changing nature of capitalism in the 21st Century. Let’s start by examining two key principals:

Gifting

Burning Man is devoted to acts of gift giving. The value of a gift is unconditional. Gifting does not contemplate a return or an exchange for something of equal value.Decommodification

In order to preserve the spirit of gifting, our community seeks to create social environments that are unmediated by commercial sponsorships, transactions, or advertising. We stand ready to protect our culture from such exploitation. We resist the substitution of consumption for participatory experience.

By elevating gifting as a virtue, Burning Man distinguishes itself from the default world which is dominated by transactional relationships between people who have no personal connection to one another. (For example, the bagger at the grocery store sees customers as largely interchangeable and the customer also sees baggers as largely interchangeable. To each the other is just a means to an ends.) Gifting is, ostensibly, about putting the needs of the other above oneself.

The principle of decommodification attempts to further separate human interaction at Burning Man from market logic. In fact, the description of the principle of decommodification even employs a Marxist concept: exploitation. (Though in the strict Marxist sense, culture cannot be exploited, only labor.)

Because no money is exchanged at Burning Man* and because gifting and decommodification are key principles of the community, Burning Man is often described as “outside the system” or anti-capitalist. However, the notion that Burning Man opposes capitalism is misguided, if not naive. In a recent interview with TechCrunch’s Gregory Ferenstein, Burning Man founder Larry Harvey spoke to this point, insisting, “We’re not building a Marxist society.” While Ferenstein’s interview highlights the comfortable relationship that Burning Man has with capitalism (particularly Silicon Valley-based enterprises), Ferenstein oddly concludes that what it opposes, instead, is consumerism.

Because no money is exchanged at Burning Man* and because gifting and decommodification are key principles of the community, Burning Man is often described as “outside the system” or anti-capitalist. However, the notion that Burning Man opposes capitalism is misguided, if not naive. In a recent interview with TechCrunch’s Gregory Ferenstein, Burning Man founder Larry Harvey spoke to this point, insisting, “We’re not building a Marxist society.” While Ferenstein’s interview highlights the comfortable relationship that Burning Man has with capitalism (particularly Silicon Valley-based enterprises), Ferenstein oddly concludes that what it opposes, instead, is consumerism.

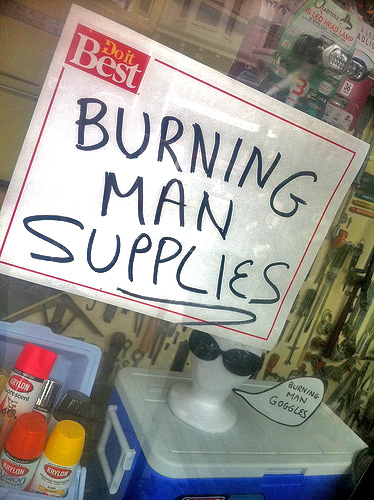

Were Burning Man’s goal to get people to consume less, it would be failing miserably. Anyone who has traveled the Reno Airport to Black Rock Desert circuit knows that an enormous consumer economy has evolved around the event. From the second you step off the plane through the very last Native American reservation before Black Rock City, advertisements suffuse the landscape, offering a wide array of commodities (bikes, tents, glowing el wire, “Indian tacos,” water, etc.) and services (e.g., rides to the Playa). And, all this pales in comparison to the vast amounts of consumer spending done in advance of the events. Camps from every major US city fill shipping containers with supplies and haul them to the desert on 18-wheelers. Many of the gifts given at Burning Man were first bought via the market economy. Burning Man’s principle of “radical self-reliance” often feeds a “get the gear” mentality of hyper-preparation, encouraging attendees to purchase supplies for every contingency they may encounter in the (admittedly harsh) desert conditions.

“Participatory experiences” alone will not shield 50,000 people from the sun or protect them from dust. It won’t even produce a fashionable pair of furry leggings or tutu. The Burning Man experience is the product of tens (or even hundreds) of millions of dollars flowing into the consumer economy and is inextricably linked to disposable incomes of Silicon Valley’s digerati. (It is also this requisite spending that keeps Burning Man as an exclusive and relatively privileged event.)

Larry Harvey’s pro-capitalist sentiments are surprising not because people misunderstand Burning Man but because people misunderstand modern capitalism. While there is certainly no causal relationship between the two, it is not entirely coincidence that a Man was first raised in the desert the year that the Berlin Wall fell. The Cold War-era perception of an irresolvable antagonism between capitalism and communism–market and commons–had begun to appear less tenable. The innovation economy that Silicon Valley has come to represent proposes to link sharing (of information) and capitalist production in a mutual reinforcing relationship. Tech companies benefit when the level of common knowledge in the employment pool increases or when innovations in the commons can be commoditized and brought into the market. (See Fred Turner’s excellent work on how Burning Man ties into Silicon Valley’s innovation economy.)

Commentators from Lawrence Lessig to Paulo Virno recognize the marriage of market and common as the underlying logic of the information economy and its chief instrument, the Web. In fact, we experience this marriage daily when we give and take freely in the gift economy of Facebook, Twitter, Tumblr, etc. (and, in doing so, make fortunes for the founders and their investors).

Similarly, the story of Burning Man isn’t a battle between capitalism (or the consumerism it encourages) and communism; instead, it is a story of the ritualized integration of market and commons. Burning Man demonstrates how market-driven consumption fuels a new commons and how this commons, in turn, creates new markets. It embodies what Virno called “the communism of capital.”

Recognizing that The Playa is inextricably linked to the market structures of the default world does not delegitimize it as a commons or as an experience distinct from our daily lives. It does mean, however, that we are responsible for the broader economic and social consequences of our big party in the desert. We cannot simply ignore, for example, the extraordinary amount of exploited labor that makes Burning Man possible or that the (mostly foreign) laborers who supply tens of thousands of tents, boots, goggle, backpacks, lights, etc. for the event will likely never be able to afford the price of admission.

It is unrealistic for anyone to expect Burning Man to exist outside of capitalism, but it is possible for Burners to participate in the economy in ways that are more socially-responsible and in ways that are less socially-responsible. If the Burning Man community truly wants to embody the progressive values of inclusivity, communalism, and civic responsibility, Burners need to start thinking seriously about issues of class and economic justice.

—

* Most attendees do, in fact, exchange money for ice, coffee, and drugs. The first two are sold by the organizers.

PJ Rey (@pjrey) is a sociologist and photographer now based in Austin.

—

Photo credits: Buy More Stuff, The Temple and The Man by Michael Holden; hand holding by PJ Rey; truck by alxndr; bikes by papertygre; woman in mask by damaradeaella; supplies by nayrb7; tents by donotlick

Comments 22

Doug Hill — September 5, 2013

Great piece.

nathanjurgenson — September 5, 2013

PJ, loved this post and especially the comment about Burning Mas as a secular religion. has anybody written that point up?

second, was surprised to not see Fred Turner's work on Google at Burning Man not discussed here.

how much of what you are saying overlaps/is different from his analysis?

last, i'd be super curious to hear you expand on the principles of what we might call "Burner Capitalism" have given that the "new" in your title suggests a separate form of capitalism is at play.

Burner Capitalism certainly has specific and unique modes of production and consumption (and thus prosumption). this quote from the original piece screams prosumption: "“The power of Google is that they don’t do all the work. People posting content do. The same is true here at Burning Man. Citizens create the vast majority of things.”"

other dimensions you seem to suggest about Burner Capitalism surround how openly capitalist it is or isn't; that is, how much does Burner Capitalism admit itself as such. there's the level of what people, both the main organizers and attendees, actually say about Burning Man and capitalism. but there would also be the level of how much Burner Capitalism as a process/system/logic actively disguises its own relationship with capital accumulation. this disguising of its own processes is, as Marx spoke about, a dimension of all capitalism. but how is this played out differently within Burner Capitalism?

certainly, the social effort to make BM seem "outside" of the world and thus economic systems further disguises capitalist workings. Burning Man is a paradigmatic example of the fictionalizing of "inclusivity" around a reality that is just its opposite. this point is parallel to the point that all capitalism is rationalistic, but McDonalds is a paradigmatic example of hyper-rational capitalism (i.e., McDonaldization). is Burning Man a paradigmatic example of the hyper state of the fetishistic hiding of the workings of capital?

a different way to ask this: in the original piece, they talk about building a more permanent burner scene in las vegas. given the yet-untheorized principles of Burner Capitalism, what would we expect here? or perhaps ephemerality is one principle so this new burner vegas thing might not work or just not be "burner"?

it strikes me that Burner Capitalism and Silicon Valley in general share some significant overlaps, and perhaps the most striking are the deeper reliance on prosumption as opposed to more separation between production and consumption. second, both seem to be a "capitalism against itself", as i wrote up previously: http://thesocietypages.org/cyborgology/2013/05/21/silicon-valleys-anti-capitalism-capitalism/ that is, capitalism that thrives precisely on superficially situating itself outside capitalism. these two, and probably more principles, taken together seem to describe a new and quite powerful form of modern capitalism...

Duff — September 5, 2013

I was just thinking this morning about how anti-consumerism has failed and morphed into hyper-consumerism. Burning Man is a great example of that. Normal consumerism is not allowed, but elaborate costumes and art cars ("maker" consumer culture) is required. You can't just show up to Burning Man in a normal pair of jeans and a GAP tee shirt.

"Radical self-reliance" becomes radical libertarianism and hyper-consumerism, even radical individualism.

I'm for less radical ideas like "gift economies" which end up just supporting existing capitalist structures and more for incremental reform, boring things like switching to banking cooperatives (credit unions).

sara — September 5, 2013

Until BM is accessible to people who dont use $ & to poor people, & also doesn't pay the goveernment (for a permis), then it is just an expensive escape for prjjvileged people. Many communities actually really don't use money such as Rainbow, Occupy, some Homeless folk, Hobo Travellers, Housless Pilgrikm. To name just a few.

Weekly Filet #127: Peek Surveillance. And more. — September 6, 2013

[...] Burning Man is the New Capitalism (The Society Pages) [...]

Ara — September 6, 2013

I think BM is an event or society that celebrates choice, independence, and creativity. As you say, much of these traits use the commerce of capitalism to come to fruition. A good question to ask is...does BM promote freedom any more or less than capitalism, in which the latter allows the freedom for us to decide whether to buy a product made from exploitation, versus, the BM culture, where you have the choice to gift or not?

That said, I look forward to going to BM next year, because being with creative, open, productive, non-judgmental people is a place I want to be...need to be. As everyone probably does.

Adam — September 8, 2013

"there are a lot of hippies who probably delude themselves into thinking BM is an escape from capitalism." -from PJ's comment, above.

For a festival centered around the burning of an effigy, perhaps it isn't surprising that there are many straw men associated with Burning Man, but this one always seems to bother me.

While I do appreciate PJ's allowance that there are many more people who don't think this (and thanks for an overall fair and level-headed assessment, rather than the polemics that normally are written about Burning Man), I'm reminded of the criticism that Occupy was somehow an inauthentic protest because protesters wore Nike sneakers and used iPhones. I don't think any Occupy protester was unaware of the superficial irony of the presence of iPhones, nor do I think that any Burning Man attendee thinks that they are actually being anti-capitalistic by going. The fact is, the mission in both cases is different.

BM is about a safe space from corporate sponsorship (creep in this area has been fought off consistently), and the promotion of a gift economy, which I think is alt. capitalism, rather than contra-capitalism. BM is fairly clear in placing itself against commodification, not capitalism. It is possible to criticize commodification without criticizing the notion of labor and property.

Many attendees might think that this criticism of commodification without a component criticism of capitalism is a lot more revolutionary than it actually is (Occupiers as well would probably call their form of protest more revolutionary than it might really be). But that doesn't quite make them hypocrites. There might be a legitimate problem in that most people have trouble defining the difference between commodification and capitalism in colloquial speech, using one as stand-in for another. But, when it comes to a real understanding of property and labor, I don't think that anyone is claiming that this exists at Burning Man.

One more thing: the costs of Burning Man are also drastically overestimated, systemically. Maybe I'm unique because I've had durable camping gear for years and years, and because I volunteer at the event. But the only costs I had to go there were for food and gas... food being fairly negligible from my ordinary weekly expenses because I cooked for myself. So, if you have to buy new camping stuff every year and go tourist class... then maybe it's expensive? I'm not saying that Burning Man is sustainable... far from it (another straw man). Goodness knows how much money you could waste going to Burning Man if you tried. But everyone talks about it like it costs $1000 minimum when I probably spent $200 tops. Just wanted to submit a contrary data point there.

Kevin White — September 8, 2013

I have never been to burning man but the concept is intriguing. I do think that the event has lost its "roots." When I heard the cost of a ticket I was shocked. I always assumed it was very inexpensive or free.

Friday Roundup (Monday Edition): Sept. 9, 2013 » The Editors' Desk — September 9, 2013

[...] in early on the “Burning man is the new…” media meme, the Cyborgs wonder if Burning Man is the new capitalism. For more on Burning Man, of course, check out our Roundtable with four sociologist/burners [...]

Burning Man is the New Capitalism by PJ Rey | anagnori — September 9, 2013

[...] From: Burning Man is the New Capitalism by PJ Rey, The Society Pages, http://thesocietypages.org [...]

Ibalu — September 20, 2013

Hi PJ. Great article. Are there any other works/links you can point me to that explore the links between festivals and the new capitalism of the commons? I am interested in the relationship between transofrmational festivals (and their culture) and market capitalism. I would be very interested in reading more on these topics.

Thanks!

Lonesomebri — September 24, 2013

Gifting and decommodification are not capitalism, no matter how much you adore capitalism. You can't simply give the term capitalism to everything you like because you love capitalism. "The new capitalism of the commons", what feebs. BM is not a new religion either, except to folks like the one who wrote this article.

Cyborgology Turns Three » Cyborgology — October 26, 2013

[…] Sarah’s work with The State’s Murmuration Festival, PJ’s work on Burning Man (1 and 2), and Nathan’s very special message to p-ed […]

Annissa — December 14, 2014

"Similarly, the story of Burning Man isn’t a battle between capitalism (or the consumerism it encourages) and communism; instead, it is a story of the ritualized integration of market and commons. Burning Man demonstrates how market-driven consumption fuels a new commons and how this commons, in turn, creates new markets."

Excellent analysis. I've been waiting for someone to contextualize "the business of Burning Man"(a phenomenon that is particularly fascinating given BM's principle of decommmodification, but that could readily be applied to the festival culture market in general)-- glad to have stumbled upon this.